The instant prégnant is the time the scene lasts in classical aesthetics. This time must at once be zero, in order to be fixed in tableau, and inscribe itself in duration, so that this tableau can be read as a story, in accordance with the doctrine of ut pictura poesis. To resolve this contradiction, which runs through all classical aesthetics, Lessing invents the notion of instant prégnant:

"Timomachus did not paint Medea at the very moment when she kills her children, but a few moments before, when maternal love is still struggling with jealousy. We foresee the end of this struggle; we tremble to see Medea soon given over to her fury, and our imagination is far ahead of anything the painter could show us at this terrible moment. [...] For its compositions, which presuppose simultaneity, painting can only exploit a single moment in the action, and must therefore choose the most fruitful, the one that will best convey the moment that precedes and the one that follows. [...] In the great historical paintings, the moment chosen is almost always a little extended, and there is perhaps no work, rich in characters, in which each of them has exactly the place and pose he should have had at the moment of the main action; for one, they are a little earlier, for another, a little later. This is a freedom that the master must justify by some artifice of disposition." (III, 56-57; XVI, 120; XVIII, 132.)

As the reference to the painting by Timomachus indicates, the example is not new. It is briefly mentioned in the article PEINTURE ANTIQUE in the Encyclopédie, written by the Chevalier de Jaucourt. But above all, Abbé Du Bos devoted a passage to it in his Réflexions critiques sur la poésie et la peinture (1719):

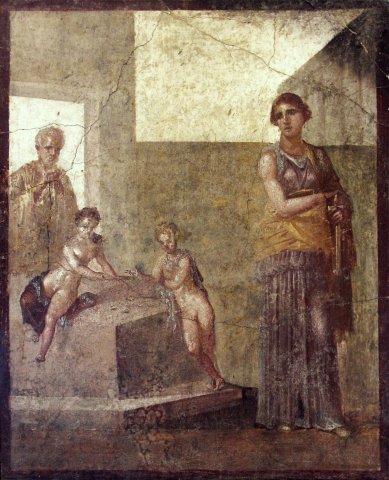

"Most of the loüges that ancient authors give to the paintings they speak of, praise expression. This is how Ausonne praises Timomache's Medea, where Medea was painted in the instant she raised the dagger on her children. We see," says the poet, "rage and compassion mingled together on her face. Through the fury that is about to commit an abominable murder, we can still see remnants of maternal tenderness." (I, 38, p. 373; ed. ensba, p. 127. See Pliny, Natural History, VII, 39; XXXV, 40; Julius Sillig, Catalogus artificum, p. 450; Ausone, Epigrammata, 129 and 130. Several replicas of this famous work can be seen in Pompeii frescoes; the best known comes from the House of the Dioscuri)

But there's no question here of a pregnant moment yet: Du Bos remains within the framework of the expression of passions, and poses the problem of their figuration, in the classical tradition of Le Brun. The mingled expression, the infigurable figure of Medea (like that of Agamemnon in Timanthe's Sacrifice of Iphigenia) criticize this semiological framework, but Du Bos does not yet operate the paradigm shift of a Diderot and then a Lessing.

In the same chapter of Réflexions critiques sur la poésie et la peinture, Abbé Du Bos evokes another ancient painting, this time by Aristides, as an example of mixed expression:

"[Pliny] relates as an important point of history, that it was a Theban, named Aristides, who first showed that one could paint the movements of the soul, and that it was possible for men to express with features and colors the feelings of a mute figure, in a word, that one could speak to the eyes. Pliny, still speaking of a painting [372] by Aristides of a woman pierced by a dagger, with the child still sucking the udder, expresses himself with as much taste and feeling as Rubens could have done when speaking of a beautiful painting by Raphael. We see," he says, "on the face of this woman, already exhausted and in the simptoms of an approaching death, the most vivid feelings and the most eager cares of maternal tenderness. The fear that her child might harm itself by sucking blood instead of milk was so clearly marked on the mother's face, and the whole attitude of her body accompanied this expression so well, that it was easy to understand what thought was occupying the dying woman." (ensba ed., p. 126. See Pliny, Histoire naturelle, book XXXV, §98, Budé p. 78: "It's from him the painting where we see, in the capture of a city, a wounded and dying mother: the child crawls towards the maternal breast; the mother seems to notice, and fears that he will head blood, instead of milk already dried up. Alexander had this painting transported to Pella, his homeland.")

This example of Pliny quoted by Du Bos probably served as a model for Frans Van Mieris's engraving of La Peste d'Athènes for the last book of Lucretius's De rerum natura (ed. Havercamp, 1725) and, from there, for the engraving chosen by Diderot for the Lettre sur les sourds. From this image, Diderot builds his theory of the hieroglyph, which constitutes a first modeling of the pregnant instant. (On the rapprochement between Du Bos, Van Mieris and Diderot, see P. H. Meyer, Diderot Studies, VII, p. 189 and Philippe Déan, Diderot devant l'image, p. 163, note 25.)

Critique et théorie

Archive mise à jour depuis 2008

Critique et théorie

Généalogie médiévale des dispositifs

Entre économie et mimésis, l’allégorie du tabernacle

Trois gouttes de sang sur la neige

Iconologie de la fable mystique

La polémique comme monde

Construire Sénèque

Sémiologie classique

De la vie à l’instant

D'un long silence… Cicéron dans la querelle française des inversions (1667-1751)

La scène et le spectre

Dispositifs contemporains

Résistances de l’écran : Derrida avec Mallarmé

La Guerre des mondes, la rencontre impossible

Dispositifs de récit dans Angélique de Robbe-Grillet

Disposition des lieux, déconstruction des visibilités

Physique de la fiction

Critique de l’antimodernité

Mad men, Les Noces de Figaro

Le champ littéraire face à la globalisation de la fiction

Théorie des dispositifs

Image et subversion. Introduction

Image et subversion. Chapitre 4. Les choses et les objets

Image et subversion. Chapitre 5. Narration, récit, fiction. Incarnat blanc et noir

Biopolitique et déconstruction

Biographie, biologie, biopolitique

Flan de la théorie, théorie du flan

Surveiller et punir

Image et événement