How should Molière be taught? Traditionally, we choose one play, for which we explain the text. But Molière's world is not one play; and this theater, perhaps more than any other, cannot be reduced to a text, without its representation. The pedagogical experiment of which this presentation is the fruit has attempted to resolve this double difficulty1.

Molière was illustrated very early on. Between the 17th and 18th centuries, the publication of the collection of his plays gave rise to three major series of illustrations, first based on drawings by Brissart in 1682, then by Boucher in 1734, and finally by Moreau le Jeune in 1773. These series have themselves been copied, diverted and adapted, resulting in a substantial corpus of images. But the principle is always the same: each piece gives rise to an illustration, which refers to a given scene, even if, in relation to this scene, the illustrator may take certain liberties.

One image per play, but all the plays: approaching Molière through his illustrations forces a synthetic approach. But above all, it's the staging that we need to talk about: Brissart most certainly saw Molière perform, and it's real sets that he draws; Boucher evolves in a completely different world, of pastorales galantes and rococo romances; Moreau le Jeune returns to the stage, but, a century later, in a completely renewed theatrical context, and while an iconographic tradition has been established, with which he needs to dialogue. Drawers create worlds, of which Molière's text is only one dimension. Approaching Molière through images allows us to encounter these worlds.

The pedagogical challenge of this experiment then also becomes a scientific one. Fundamentally, the image is transgeneric: from tragedy to farce, from theatrical acting to the painting or novel scene, the visual device circulates, borrows, diverts, counterfeits. Beyond the designer's strategies, it reveals Molière's relationship with the novel stage, a relationship of appropriation and reversal, from which the verbal game unfolds. From this relationship, it is then possible to return to the text, in an attempt to understand the implications for Molière of the use of speech, and the (irrepressible and catastrophic) overflow of this living speech from the dead speech of the written text. Using three examples, we propose to use images as a starting point to identify what defines Molière's speech as an overflowing speech.

.I. Topique of surprised intimacy: Dom Garcie de Navarre

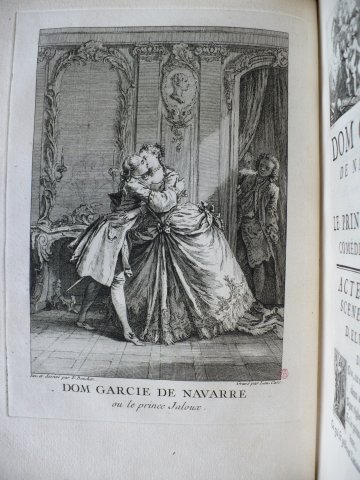

The couple seems to be kissing mouth-to-eye, reflected in the overmantel of a composite mirror, the grid and joints of which can be made out. The princess's ample dress, with its train, bangs and pleats, forces her partner to lean forward, arch and stretch to reach her. On the right, in the background, a decomposed witness observes the embrace from the threshold of the room, from which he already regrets having drawn aside the curtain. His companion can be seen behind him, in the shadows.

Dom Garcie de Navarre is the jealous prince, smothering Elvire with his shady suspicions. He was first given a torn letter, which he interpreted as a declaration from Elvire to her rival dom Sylve (II, 4) : Elvire disabused him of this notion by giving him the complete letter, which was intended for him, to read. Then he surprised Elvire in a tête-à-tête with dom Sylve (III, 3) and didn't want to believe her unexpected arrival, and that he was being spurned. Finally, as he prepares to enter the stage with his confidant dom Alvar, he thinks he sees "A man in the arms of the unfaithful Elvire" (IV, 7, 1241). The jealous lover catches the unfaithful princess unawares, and deploys the scenic device from his gaze, which breaks into his forbidden intimacy. The jealous lover's gaze is barred by the curtain, stopped at the threshold of the stage, which he misunderstands: from behind the dress, from Elvire's back, Dom Garcie misinterprets the intimacy he surprises and which makes a tableau for us, against him.

For what is at stake here is not at all what he thinks. A detail offers itself to our gaze, which, from the backstage where he stands in the background, he cannot see: the man in the arms of the unfaithful Elvira wears an earring; his smooth face is that of a woman, of Done Ignès who has donned the habit of a cavalier to escape her pursuers by pretending to be dead (IV, 4):

"The secret of my fate must be hidden from everyone,

To see me safe from unjust pursuit

Who might in these places persecute my flight." (v. 1163-5)

The guilty embrace of the unfaithful lover turns out to be an innocent kiss between two princesses united in persecution. There was nothing to see but the fantasy of a jealous mythomaniac, there is no real scene.

Through a tour de force by Boucher in the drawing, and his engraver Laurent Cars, the kissing couple is reflected in the mirror. This reflection has no practical use in the scenic device: accessible only to the viewer-reader of the engraving, it only shows the reverse side of the embrace, which is delivered to us head-on. The disappearing earring, the blur of the irregular mirror, the crack of the tiles joined at the point where the faces meet, the two candles framing the misty couple like a consecration of scandal, the two pigeons of gilded woodwork pecking at each other, draw Dom Garcie's fantasy, and figure for us what he thinks he sees instead of what we see.

Above the dummy couple, a bas-relief portrait in the Roman style hangs, signifying the noble style of tragedy: and indeed the staff of Dom Garcie de Navarre is the staff of tragedy, with princes, princesses, confidants, confidantes, kingdoms to be filled and crowns usurped.

And indeed this scene is not, is no longer, a theatrical scene: we can't relate it to any actual stage moment in the play. When, at the beginning of Act IV, Scene 7, Dom Garcie thinks he sees Elvire in a man's arms, it is Dom Garcie who is on stage, and Elvire who must be assumed to be in the wings, or at their threshold. Dom Garcie does not appear; he was already there in scene 6, assuring Elvire's confidante Élise of the good resolutions he had made against her jealousy, by disgracing the courtier who maintained her:

"Tell him that I first banished from my presence

. He whose opinions caused my offense,

That Dom Lope never..."

In scene 7, the vision has already passed: the dialogue that ensues between Dom Garcie and his confidant Dom Alvar is a representation of its aftermath:

"What do I see, O righteous Heavens!

Must I make sure of the report of my eyes?

Ah! doubtless they are too faithful witnesses to me,

This is the dreadful culmination of my mortal sorrows,

Here is the fatal blow that was to overwhelm me" (v. 1222-1226)

On stage, in the theater, Molière didn't plan for us to see what Boucher draws, at least not as a painting. Dom Garcie, the tragic hero, is inhabited by a vision without representation, a vision he communicates to the audience through an overflowing speech, overwhelmed by the fantasy that embraces him. Boucher does not draw the theatrical scene of this overflow, but the novel of this fantasy.

It's an impossible scene: the mirror reflects what Dom Garcie may have caught a glimpse of, but from where he emerges Dom Garcie can't see the mirror. Elvire may have embraced Done Ignès in a gesture of friendship and compassion, but this abandoned, lost kiss, this arching and embracing do not represent a possible reality of the event; they actualize Dom Garcie's fantasy. Even the earring is not an absolute sign of femininity in the dress code of the early eighteenth century.

The text of the 1734 edition attempts to bridge this hiatus from scene to novel by adding, at the start of scene 7 a didascalia: "Dom Garcie, looking through the door that Élise has left ajar ". But, let's remember, it's Dom Garcie who's on stage, and Élise by leaving allows him at a pinch to catch a glimpse of Elvire outside.

Boucher thus rediscovers the central device of the novel scene, inherited from the short story: the neighbor spying on the husband frolicking with his mistress in her garden, in La Servante justifiée ; Joconde surprising the queen with her dwarf, in Ariosto and in La Fontaine; Valville surprising M. de Climal at Marianne's feet in Marivaux's novel. Molière overturned this device by turning it into a fantasy: Dom Garcie believes that things happen as they do in novels, he thinks he's seeing a scene from a novel and experiences a kind of romantic deception. The theater feeds on this testing, this failure of the novel.

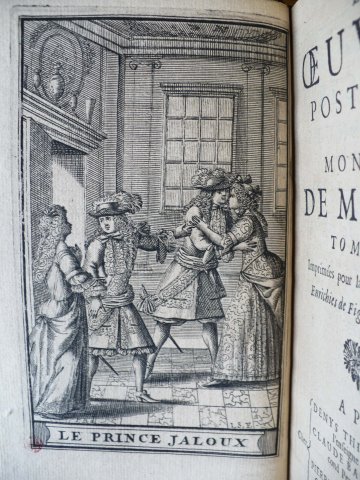

The original 1682 engraving, by Jean Sauvé after a drawing by Pierre Brissart, was obviously used as a model by Boucher, who therefore did not work directly from Molière's text, and was unable to see the play performed: created in 1661, Dom Garcie was unsuccessful and, after a few performances in 1662 and 1663, the play disappeared. Brissart's engraving depicts the same moment in the play, but in the theatrical sense: Dom Garcie is center stage, acting as mediator; as he leaves Élise, foreground left, he sees Elvire in the corridor, background third, in an equivocal situation. The performance emphasizes the skilful sequencing of the two scenes, with no break in continuity. The actors are divided into three planes, bounded on the left by the door opening and on the floor by the paving: Élise stands against the open door, Dom Garcie in the opening, Elvire and Ignès near the windows. In Jacobus Harrewijn's engraving, the effect is even clearer: the two silhouettes are silhouetted against the leaded bars of the window, behind which the vague space of the city can be seen. They are painted as set pieces, that is, as objects rather than subjects of the theatrical performance. Boucher's reflection on the overmantel, where the joints of the glass panes fade and melt, remains from this capture of fantasy in the tableau of a gridded representation. The difference between the place of the scene and the tableau of the vision fades away.

Why is this vision of Dom Garcie, which manifests itself only in the interstice between two scenes, chosen as an emblem for the play? The whole play is inhabited by a dysfunction of speech: Dom Garcie should keep quiet, control himself, shut himself away; but inquisitive speech, jealous questioning, can't help gushing out. At the threshold of Molière's theatrical production, Dom Garcie posits an overflowing word to which corresponds an overflowing image, a phantasm in place of the stage, a fleeting tableau that is immediately faded. The mechanism of the Molière scene then emerges, as a coincidence of an overflow of speech and an overflow of tableau, playing with the codes and topics of instituted representation, which he summons up and turns upside down. Boucher recovers as a model what Molière had provided as a phantasmatic interstice: this recovery, this novelistic institution of theatrical scenic overflow consecrates the tipping over and transgeneric universalization of the stage as a medium of representation.

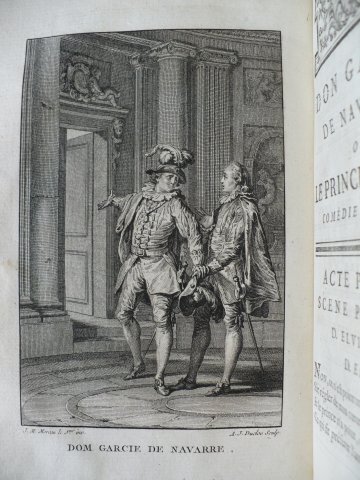

The drawing by Moreau le jeune in the 1773 edition is a commentary on the theatrical impossibility of the scene drawn by Boucher: from the stage, Dom Garcie taking Dom Alvar as witness can only point to a half-open, empty door. The painting of Elvire embracing a stranger cannot take on any visible consistency, and can only be held together by the delirious words of the Jealous. The stage opens onto a void, the void of the tragic chamber, which in 1773 could be represented as empty. The time is no longer ripe for unifying the scenic medium and insisting on fluid scene transitions, as with Brissart a century earlier. Triumphant, the stage closes in on itself and reveals its rift of silence and invisibility, through which the whole substance of classical representation will unravel.

.II. Commentary on the text kills the text: lessons from Misanthrope

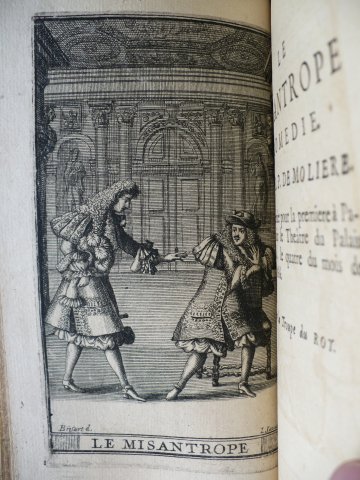

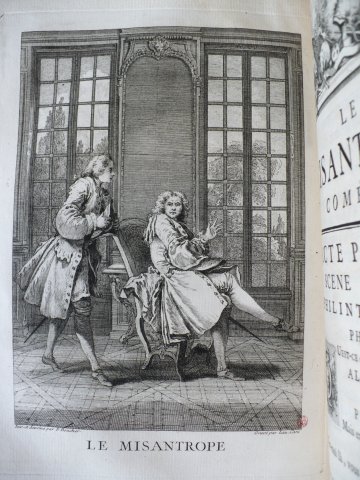

The failure ofDom Garcie commits Molière to a clear break with the tragic model. But the material of Dom Garcie would feed into all his later work, and in particular Le Misanthrope. Sauvé's original engraving after Brissart depicts an elegant man on the left, wearing a gentleman's sword and an abundant wig, holding under his arm a plumed hat provided and in his hand gloves trimmed with lace. The lace also spills over his sleeves, as he gracefully curtsies to his antagonist. The character on the right, whose figure can be identified with that of Molière himself, is the exact antithesis of the comely courtier: the graceful entrechat on the left is opposed by the engrossed ennui on the right, a small man, withdrawn into himself, sitting awkwardly on the corner of his chair, deranged.

The text of the Misanthrope soberly states that "the scene is in Paris": but the presence of the chair and the ornate coffered ceiling let us know that we are inside a house, despite the pompous luxury of the background decor, which is reminiscent of a palace facade. The engraving is generally interpreted as illustrating the first scene of the play, between Alceste and Philinte. "What is this? What have you?" asks Philinte of his friend Alceste, the misanthrope, who evades him by replying, "Leave me be, I pray you."

I don't think this identification is accurate. "Laissez-moi là, vous dis-je, et courez vous cacher", exclaims Alceste: the text gives the feeling of a first scene in motion, Alceste is furious, exalted, he pursues Philinte with his anger, he is standing, and the chair would have no scenic justification there. Faced with Alceste, Philinte is not the swaggering courtier, but the friend at heart, moderate, speaking frankly and not in the midst of bows. Another frontispiece from an English edition, signed by Gerard Vander Gucht, depicts the same courtier salute on one side, with Alceste's posture of wrathful refusal from his chair, and bears the explicit indication "Act 1st Scene 2d". The engraver, who copied Brissart as the inverted layout betrays, has therefore interpreted the elegant figure not as Philinte, but as Oronte coming to read his sonnet to Alceste and beg for his approval:

"I heard there that, for some shopping

Éliante went out, and so did Célimène;

But as I was told you were here,

I went up to tell you, and with a true heart,

That I have conceived for you an incredible esteem" (I, 2, v. 250-4)

Oronte has just entered, spouting his courtier compliment, he hasn't yet taken his sonnet out of his pocket; unlike Oronte, Alceste is already on stage, he's just got carried away, his fury at his friend Philinte succeeded by melancholy and despondency. For this reason, he sits down, exhausted and wishing to be left alone. Oronte comes up behind him and surprises him:

"It is to you, please, that this speech is addressed.

In this place Alceste looks all dreamy, and seems not to hear that Oronte is speaking to him.

To me, Monsieur?

Alceste's gesture, disturbed in his melancholy despondency, corresponds to this "À moi". In the engraving after Boucher, the pompous decor has disappeared: Oronte advances timidly behind Alceste, whose averted face (this is exactly the moment of the "À moi") comes to be inscribed on the mirror's overmantel, between the two bay windows. The mirror, echoing that of Dom Garcie, reflects nothing: Alceste's mind is empty. The emptiness of the mirror, very lightly squared by the joints of the tiles that make it up, figures Alceste's empty absorption, abstracted from the social space where he sits.

At Boucher, Alceste is no longer disturbed at the corner of his chair: he sits masterfully, crossing his knees nonchalantly, a crumpled plaid behind him. By the window, he meditates, and is disturbed. Behind the windows, it's not Paris, but a park. Alceste already prefigures Carmontelle's portraits, where the physiognomy is captured in the carelessness of an unadorned snapshot, where the frame of the scene falls away and space opens onto the vague elsewhere of a site. Alceste listens, Oronte attentively watches for his reaction: it's a boudoir conversation, like those found in Marivaux and Crébillon at the time Boucher was drawing. But Alceste is seated upside down, with his back to his visitor, rather than facing him: with this upside down position, Boucher immediately reveals Molière's scenographic intention, which assumes a ritual of sociability and turns it on its head: as Philinte points out in the next scene, Oronte came simply to be flattered, there was no question here of Alceste sincerely giving his opinion on the sonnet. All the dramatic tension of scene 2 rests on this departure from the expected ritual with what Alceste ultimately withholds, then delivers: an incongruous sincere word, which can't help but spill over.

"Monsieur, I am ill-suited to decide the matter;

Please excuse me. - Why?

- I have the defect

Of being a little more sincere in this than is necessary." (v. 298-300)

Alcestis defends himself foot to foot against the catastrophe to which the very ritual of flattery pushes him, and elicits a beautiful imaginary spirit to address the irrepressible bile of his remonstrances:

"But one day, to someone, whose name I'll keep quiet,

I said, on seeing verses of his,

That a gallant man must always have great empire

On the itches that take us to write;" (v. 341-6)

In a way, the imaginary other is the inverted reflection of Alceste himself, who since his misanthropy can only imagine the worldly man as a man inhabited by vain speech that he cannot curb: worldly overflow and melancholy overflow proceed from the same movement.

Between the two interlocutors, then, is this imaginary being that Alceste constructs in his inverted image, and in which Oronte recognizes himself. What makes up the tableau in the scene is invisible, carried by Alceste's speech, imaged in Boucher's work by the empty mirror, which here plays the same semiological role as the mirror in the print illustrating Dom Garcie.

In the 1773 edition, the print engraved by Duclos after Moreau le jeune illustrates an entirely different scene, Act IV, scene 3, where Alceste, brandishing an unsealed letter from Célimène, which he thinks is addressed to Oronte, accuses the young woman of infidelity. Alceste, on the left, almost steps on Célimène's dress, whom he obsesses; she, who had her back to him, half-turns, her right hand pointing to the ground with a folded fan in annoyance. Between them and the back door, an interposed screen blocks any possible intrusion.

Moreau le jeune doesn't choose a new scene from the text. Each new illustrated edition comments on the previous ones, interprets the choices made by their illustrators, and adapts these choices to new tastes. The choice of illustrator does not obey a specific textual logic, but, more globally, a logic of device: in the theatrical machine of a play, the aim is to isolate a scenic device that will represent the whole play, and give an exclusively visual legibility to a composite whole, where enter a text with its articulations of plot and reasoning, a staging with its sets, backstage and lighting, an acting set with its postures and gestures, mimics and voice inflections. The illustration is a visual reduction of this whole, of which the text is only one element.

Moreau le jeune's drawing parallels Boucher's: Oronte approached Alceste, who had his back to him, and pretended to read him a sonnet; Alceste approached Célimène, who had her back to him, and pretended to read him a letter. Oronte disturbs Alceste, who disturbs Célimène. Between Oronte and Alceste, a text interposed the screen of a presence as invisible as it was importunate; between Alceste and Célimène, the same invisible screen, the same importunity. Narratively, morally, the situations have nothing to do with each other; scenically, it's the same set-up, with, for the scene illustrated by Moreau le jeune, the merit of clarity. If we pay attention, the designer even winks at us with a mischievous wink: it's not exactly the floor, but the seat that Célimène points to with her fan, i.e. the spot from which, in act 1, scene 2, Alceste insulted Oronte. Since Moreau the Younger, Célimène has been pointing at Boucher; since the 1773 image, she's been pointing at the 1734 one.

The letter scene, taken directly from Dom Garcie de Navarre, is closed in on itself by the illustrator: the empty depth of Brissart's parlor, Boucher's windows and the open phantasmagoria of a park taking shape behind the latticed windows are succeeded by the clutter of a boudoir embarrassed by furniture and barricaded by a screen. The progression of the sequence, the transition from one scene to the next, no longer produces its flowing effect: Alceste stumbles against Célimène's dress, which, with its fan pointed at the ground, puts an end to the movement. The scene freezes into a tableau, becomes a fixed, standard model of representation.

Verbally speaking, the entire scene is tense between the text of the letter, to which Alceste would always like to return, and the code of gallant conversation, for which Célimène makes herself a bulwark. Alceste would like to stick to the text: "Ce billet découvert suffit pour vous confondre" (v. 1325); "Vous ne rougissez pas en voyant cet écrit?" (v. 1328); "Tous les mots d'un billet qui montre tant de flamme" (v. 1354); "Ce que je m'en vais lire" (v. 1356); "De me justifier les termes que voici" (v. 1360). Molière's art lies in showing that there is more to theater than the words that mislead Alceste. Alceste gets carried away, his words overflowing from the letter that was supposed to confound Célimène simply because it is shown, to the need to read the letter, then to the need to interpret it, finally, from interpretation to the sheer brilliance of reproaches:

"My pain and suspicions are pushed to the limit,

They let me believe everything, they glory in everything" (v. 1375-6)

The poem, the letter are, in the image, what of the text, not resists towards a higher meaning, but quite the contrary dies for the representation for having resisted its theatrical, spectacular, visual conversion. At the end of the scene, Célimène notices the defeated face of Du Bois, Alceste's servant, who comes to the door to announce to his master the loss of his trial, ruin, the risk of prison:

."Here is Monsieur Du Bois, pleasantly figurative." (c. 1435)

To the figure of Du Bois, where Célimène disregards the external, real catastrophe, correspond the figures of the letter, the "words", the "terms" that Célimène refuses to confess. It's necessary to leave the figure to speak the real; but this overflow carries with it the loss of who triggers it and the incomprehension of who receives it.

III. Dehors est dedans: L'École des femmes

Moliere's theatrical project is inscribed in this tension: on the one hand, the institution of speech, the normalized, policed, ritualized practices of language, the compliment, the gallantry, the diagnosis, the contract, which lie, disappoint, resist, designate the foundation of representation as the dead foundation of the text's textuality. On the other hand, the overflow of speech, the irrepressible movement of expressing what has been contained, the impossibility of stopping oneself from speaking, as the living force of theatrical play, as an irruption outside the norm of character, of type: but this overflow is not of truth either, it swells, spills out, disfigures speech into the madness of language and wallows in the pas-de-sens of paranoid delirium. This tension of speech is embodied in the visual device of the stage: from the stage, something forms a tableau, but as an interstitial image (Elvire glimpsed with Ignès), as the body and object of the crime: a sonnet, a letter, a book, ridiculous, illegible, indecipherable. The stage play stops at the threshold of this image, this object, and orders itself around this invisibility. In this way, the screen of the performance is established: the stage shows this threshold and its beyond; it stops the characters at the threshold, condemning access to what they see. And yet this invisible that they see constitutes the mainspring of theatricality.

Tragic fate at its core, since vision is traded for madness, and visibility comes at the price of sacrifice. Molière doesn't simply choose to laugh about it: where tragedy pits aristocratic heroism against the worldly institution, Molière substitutes madness for heroism. The logical aberration of the discourse is then matched by a visual aberration of the stage, echoed to some extent by the illustrations.

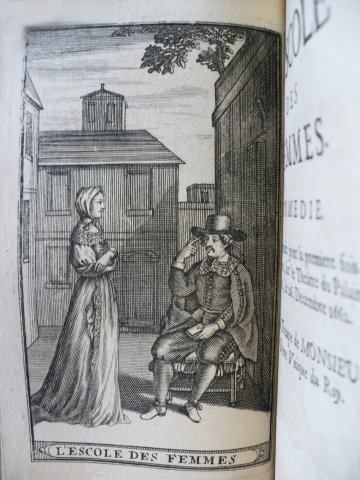

To illustrate L'École des femmes, Brissart depicts, in the typical town square of the comedy set, Arnolphe seated on the right, Agnès standing on the left. We're at the start of Act III, Scene 2, and the didascalia specifies that Arnolphe is seated:

ARNOLPHE, seated.

Agnès, to listen to me, leave your work there.

Lift your head a little and turn your face:

There, look at me there during this interview,

And print every word of it.

Arnolphe has placed a small opuscule on his lap: it's the Maximes du mariage, which he's about to have Agnès read. Facing him, attentive and obtuse, Agnès looks at him, as her mentor instructs with the index finger of her right hand, pointed at his eye. The space of the scene is aberrant: Arnolphe is seated and talking inside his house, or at least in his garden; but by convention, the comedy stage is a town square, a public space, and therefore external. The wall on the right, with its overhanging foliage, metonymically designates the interior where things are supposed to take place, while the houses in the background, in foreshortened perspective, symbolize the city but in no way represent it realistically: the actors wouldn't crawl in there... Between the side facades and the backdrop, a space is left: we can certainly imagine a street, but in practice this space is necessary to hang the various set elements from the backstage racks. The very aberration of the space tells us that Brissart isn't imagining his drawing from the text, but from a real, concrete representation of the play in the theater.

Boucher copies Brissart, as indicated by the inverted arrangement of the figures; but he de-theatricalizes the space of representation, or more exactly he normalizes it, bringing it back to the conventions of the pictorial scene. The public square has disappeared, the figures are arranged in the patio of a townhouse overgrown with vegetation, linear Italian perspective has been restored: this is the rococo setting of the pastoral, familiar to Boucher, and the site of a novel scene as found, for example, in Paméla. Arnolphe is no longer outside: he's put his hat back on the corner of the back of his chair, spread a plaid on his lap, let his back flow backwards; he's neglected.

Boucher no longer understands Arnolphe's gesture, intimating with his index finger that Agnès should look at him, and speaking to her by signs as if, completely idiotic, she were inaccessible to language. He thus shifts the index finger from his eye to the fool's forehead; at the same time, the 1734 edition adds the didascalia: "Mettant son doigt sur son front" ("Putting his finger on her forehead"). It is on her forehead that Agnès must imprint the maxims of marriage; it is no longer a living word that we hear, but its visual translation as text and as sign.

The text of the Maximes is the instituted word that attempts to reduce Agnès: it should be possible to explain this text, to develop it, Arnolphe is constantly tempted to do so: "Je vous expliqueai ce que cela veut dire" (v. 752), "Je vous expliquai ces choses comme il faut" (v. 303). But to explain it is to pervert it, to give the idea, to develop the imagination, to open up the possibility of the transgressions he represses. The whole scene is tense between this absurd text, incomprehensible to Agnès, and the outburst of speech that Arnolphe refrains from. Molière's theatrical machine tends to identify the text with the death of desire, the meaninglessness of textuality with the gagging of femininity. The text forbids writing to the woman who, in addition to prohibiting gallant commerce, must not become a precious: "There must be no writing-table, no ink, no paper, no quill" (v. 781). Between Arnolphe and Agnès, the text acts as a screen, as a place where the living word tips over into dead textuality, the woman of desire into the sequestrator of marriage.

.But this tension of restrictive speech and its paranoid overflow is only visually converted into the screen of representation in Moreau the Younger, who introduces the third, missing term of desire, Horace as beyond the face-to-face between Arnolphe and Agnès. In both Boucher and Brissart, the resistance of the text remains the interpreter of the scenic device. Yet Molière, through Horace's voice, insists heavily: it is through the screen device that Agnès gains access to desire.

Sure, Agnès has thrown a sandstone at Horace from her balcony, but Horace guesses that Arnolphe was behind her ordering this gesture: from the presence of this ordering witness to the scenic break-in comes the shared enjoyment of the two young lovers.

"And I understood at first that my man was there,

Who, unseen, was driving all this." (III, 4, 394-5)

Horace then joins Agnès in her bedroom, but the baron appears:

"And all she could in such an accessory,

Was to lock me up in a large wardrobe.

He came in first: I couldn't see him,

But I could see him walking, without saying a word, with great strides" (IV, 6, 1152-1155)

Hidden Horace becomes the blinded voyeur, separated from the scene where Agnès and Arnolphe are, and constituting that scene from that separation, in terror and jubilation. Finally, when he returns a third time, climbs the ladder and, surprised by his assailants, slips and falls, Horace is once again caught in a device where he makes himself known to Agnès while he passes for dead in the eyes of the others (V, 2).

Agnès first writes a letter with the sandstone she has discarded; she then locks Horace in to spare Arnolphe's silence; she finally flees with him: the text is still the interpreter of the device in the first attempt; silence is achieved, but sight is not yet established in the second; the third slips from reported narrative onto the theatrical stage to complete the visual shift.

This is the scene that Moreau the Younger decided to illustrate. The scene depicts the driveway leading to Arnolphe's house, which we can imagine is on the left, behind the high tree-lined wall. Arnolphe, wrapped up in his cloak so as not to be recognized by Agnès, pulls her towards the back of the stage, while the young girl, turned towards her lover, resists, delays the moment of separation, wanting to express her tenderness and concerns. The stage tension is physically represented by the two arms pointing in opposite directions, the right one held by Horace's hand, the left one grabbed and pulled by Arnolphe. Moreau le jeune thus recaptures the layout of Boucher's engraving for Dom Garcie de Navarre.

We started with a little-known play, which in a way gave us the topical basis from which Molière deployed his talent. The jealous man who has to hold back his questions, the overly sincere misanthrope, the baron who wouldn't want his white goose to get any ideas, are all characters inhabited by the same relationship to speech. It's not exactly a voluble, overflowing speech; it's a speech that overflows in spite of themselves and that the stage objectifies as a game: an overflowing speech.

This vivid speech, which runs to catastrophe, focuses on, attaches itself to the text it brandishes, questions, stigmatizes: it's a letter, a sonnet, it's Maximes du mariage ; elsewhere - a contract. The stage designates, from the living, catastrophic word, the dead word, as the institution of artifice, as the fundamental lie of the text. From this lure, the theater unfolds its fantasies, imagined by Boucher's mirrors, Moreau le Jeune's gaping door, Brissart's high walls: the real stage, the one that haunts the characters, therefore lies well offstage, in the text. The trick, beforehand, is to put it to death...

Notes

I would like to thank Stéphanie Clérissi, literature teacher at Lycée Bristol in Cannes, and her Première students for their intense and active collaboration in this experiment, which resulted in the production of a DVD. Thanks also to Marie-Lucile Milhaud and Isabelle Polizzi, IPR of the Académie de Nice, for making this collaboration possible. I'd also like to thank Elisabeth Maisonnier, from the Versailles municipal library, who enabled me to photograph the engravings for Utpictura18, and Aurélie Bosc, from the Méjanes library in Aix-en-Provence, thanks to whom the students had access to the books. Finally, this work was presented in a workshop at the second Séminaire national des lettres co-organized by the Inspection générale des lettres and the Bibliothèque nationale de France on November 23 and 24, 2011. May Catherine Becchetti-Bizot, who enabled us to present our work there, receive here the expression of my gratitude.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Molière, une parole débordée », atelier du Séminaire national des lettres, Les Métamorphoses de la lecture : lire, écrire, publier à l’heure du numérique, novembre 2011.

Ce travail a également fait l’objet d’une conférence à l’université Bar-Ilan le 28 décembre 2011.

Fiction, illustration, peinture

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Fiction, illustration, peinture

La scène de roman

La scène de roman : introduction

Renaud dans le jardin d’Armide

Rastignac chez Mme de Restaud

Gilberte derrière les aubépines

La poignée de porte de tante Berthe

La double aporie du topos

Illustrer la fiction

Molière, une parole débordée

Marillier, l’appel du mièvre

On n'y voit rien

Illustrations de l'utopie au XVIIIe siècle

Le temps des images

Du conte au roman graphique

Déconstruire l’illustration

Régimes de la représentation dans la gravure d’illustration classique

Penser la fiction depuis la peinture

Une sémiologie du décalage : Loth à la scène

Introduction à la scène comme dispositif : Paolo et Francesca

La main tendue, le regard démasqué

De Silène molesté à la chair blanche des nymphes

Chambres de la représentation

L'intimité de Gertrude

Brutalités invisibles

Parodie et pastiche de Poe et de Conan Doyle dans Le Mystère de la chambre jaune de Gaston Leroux

Le dispositif de la chambre double dans Les Démons de Dostoïevski

Scène pour voir et chambre des brutalités

La Princesse de Clèves

L’invention de la scène dans le roman français

La canne des Indes

L'aveu

La princesse, la religieuse et l'idiot

Richardson

Entre scandale et leurre

Introduction aux Lettres angloises, ou histoire de miss Clarisse Harlove, par Samuel Richardson