E tenebris autem quae sunt in luce tuemur.

(De rerum natura, IV, 337)

" It's not enough to hear me speak, I told her, you must also see me. - I believe," she replied, "that neither is necessary."(I, 15, 123.)

This banter between Garigues, a.k.a. Le Destin, and Mlle de Léri, a.k.a. Madame Madelon, in the garden of Saldagne, who is not only the brother of Verville's mistress, but also the failed abductor of Léonore, a.k.a. Mlle de L'Étoile, pretty much sums up the difficult relationship that the narrative of the Roman comique deftly maintains with sight : because of the darkness, we can't see a thing in the meetings she organizes, and when the light is there, it's a mask, a veil, a plaster that prevents us from recognizing characters whose complicated, blurred identities foster inextricable misunderstandings.

" Ce n'est pas assez de m'ouïr parler, il faut aussi me voir " : speech is here the supplement not only of visual recognition, but of a pleasure to see. Mlle de Léri, who enjoys Garigues' meagre conversation, and recognizes in his terseness the nobility of heart of her interlocutor, would benefit from seeing a well-made face. Yet she distrusts both, recognizing in them the trappings of seduction. You can't see it, because you'd be tipping over into romance. We see nothing, as a trademark of the comic novel, that is, of the low novel, ingeniously conjuring the solar visibilities of Baroque fiction.

From the outset, the sun falls :

" The sun had completed more than half its course and its chariot, having caught the inclination of the world, was rolling faster than it wanted. " (I, 1, 37.)

The dusk of the first part is outdone by " une nuit fort obscure " at the start of the second :

![Ragotin est renversé dans la boue, in <em>Vingt-six scènes piquantes du Roman comique de Scarron</em>, Paris, Desnos [1760?], copperplate engraving, Versailles, Bibliothèque municipale centrale, Rés. J-58](/system/files/styles/crop_thumbnail/private/notices/007/haute_def/007897.jpg?h=8e472d3a&itok=efA60ZIO)

" The sun gave lead over our antipodes and lent his sister only as much light as she needed to conduct herself in a very dark night. " (II, 1, 195.)

On one side, then, a sun chariot tilting to announce the late arrival of the comedians at Le Mans on the other, a moon chariot advancing, as it were, groping under a sparse light. In a way, these two parodies of baroque triumph foreshadow all the embarrassed, hurried vehicles of the rest of the novel : La Rancune's stretcher stuck in a quagmire (I, 7, 56) the abduction of the curé de Domfront and the stumbling horse on his stretcher (I, 14, 111) ; the story of the miser who, before dying in the hostelry, walked barefoot beside his unshod horse (II, 6, 221) Ragotin taken for the village fool because he was naked, kidnapped by the peasants, then poured into the mud (II, 16, 296).

I. Some /// something unrecognizable

The birth of the Count of Glarus

Loss of visibility or shameful fall, it's all one. Both darkness and fall taint the scene with perpetual suspicion. The trivial and the lowly lurk in the shadows. We fall so as not to have seen, so as not to have been seen the unrecognizable is at work. We've seen something something means we can't see anything. The something is sometimes marvellous, like the flash of a supernatural encounter just before the birth of the Count of Glarus. Destiny's father is on the road, in the middle of the night :

" ... he saw from afar, in the moonlight, something bright crossing the street. [...] The place where she was received enough moonlight to make my father discern that she was very young and very well dressed ; and this was what had shone to his eyes from afar, her habit being of silver cloth. " (I, 13, 93-94.)

The silver brocade of this dress from Peau d'âne attracts the concupiscent eye of the miser, who otherwise " didn't put much stock in what it was ". When you can't see anything, there's no identity, no possible identification reality gets bogged down in a blurred vision, and the eye finds a certain satisfaction in this bogging down. The brilliance of the " something " indicates what could be the beginnings of a noble fiction, which the narrative strives each time to conjure, to normalize.

Combat de nuit pour le mot de cocu

A few pages earlier, still in the middle of the night, but this time in the Le Mans inn, Destiny hears from his room a whole hullabaloo :

" He entered the room from which the rumor came, where he saw nothing, and where the thumping, bellows and several confused voices of men and women beating each other, mingled with the thud of several bare feet stamping about the room, made a dreadful rumor. [...] At the height of the fight, he felt himself being bitten in the fat of the leg he put his hands to it and, encountering something furry, he thought he was bitten by a dog " (I, 12, 89).

In the darkness, rumor, voices and stamping are a poor substitute for the geometrical arrangement of figures and places : the theatrical visibility of the scene cannot be established, the visual event of the encounter degrades into a sensation of bite ; Fate is confronted with " something furry ", an animal aggression, faceless, the brutal abjection of the relationship to the absolute Other, a relationship that is not even a face-to-face, because there is no face.

" ... but the Cavern and her daughter, who appeared at the door of the chamber with light, like St. Elmo's fire after a storm, saw Fate and made him see that he was in the midst of seven people in shirts who were undoing each other very cruelly and who decramped themselves as soon as the light appeared. [...] Fate wanted to separate them, but the hostess, who was the beast that had bitten him and whom he had taken for a dog, because she was bareheaded and short-haired, jumped out at him, assisted by two servants as naked and dishevelled as she. "(Continued from previous.)

The projection of light on this obscure mêlée introduces the distance of the scene : faced with the tumult, the abjection of darkness and its blows, the external gaze of the Cavern and her daughter establish a field, from which to unravel figures, a disposition. " Like Saint-Elme's fire after a storm ", the providential arrival of light re-establishes an order of things, that is, an order of visibilities : the two women " seen Destin and made him see that he was in the midst of seven people in shirts ". Saint-Elme's fire is an electrical phenomenon, generally observed at sea Saint Elme, or Erasmus of Formia is a patron saint of sailors the storm evoked by /// Scarron is a storm at sea it's not just a matter of metaphorizing the brawl it's the very place of the scene that's at stake, a place that, in darkness, slips out from underfoot, an unstable and shifting place that the arrival of light stabilizes and, in so doing, opens up to geometrical representation.

Of course, we mustn't exaggerate the distressing dimension, the nightmarish horror of this pre-scene night : the sequence is essentially burlesque, and comic. St. Elmo's fire is an element of epic decor, found in Ariosto, for example, and contrasts comically here with a ragpicker's brawl caused by Roquebrune's insomnia, when the poet gets up in the middle of the night to ask for candles and write "the two most beautiful stanzas one had ever heard" (I, 12, 90). We mustn't forget, however, that the mainspring of comedy is the sudden lifting of an underlying anguish what makes us laugh is the lifting of this hypothec, the conjuring of the liminal " on n'y voit rien ".

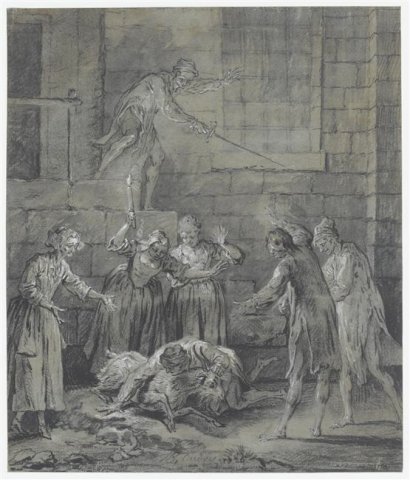

The scene is illustrated as early as the first iconographic program concerning Le Roman comique, by one of the paintings in the series executed in 1720 by Pierre Denis Martin for the Château de Vernie, near Le Mans. Martin admirably renders the effect of contrast, which casts a harsh light on a generalized disorder. The scene is not yet in order, and what comes into view is rather an obscure tumult, brutally delivered to the eye. Contrary to the indications in the text, the light comes from both right and left, to illuminate two parallel groups: on the left, Fate spanking the hostess who bites him; on the right, the host should logically be occupied with Roquebrune's behind, who has called him a cuckold, but it seems that Martin preferred, for the eye, to stage a woman's behind. The two playlets are separated by a chair; they each have their spectators, their play of chiaroscuro. One could almost cut the painting in two, as Martin has done elsewhere, representing two distinct episodes on the same canvas, separated by a line.

So, even with the light back on, we continue to see nothing there. A few years later, in 1727, Oudry redesigned the scene and brought order : the chair that cut the space in two falls to the ground, creating an intermediate visual clutch in the foreground a portrait placed on the back wall in the upper middle unifies the space, which is now polarized between left, with its ajar door from which the Rappinière arrives, who " stopped the blows in the name of the king " (I, 12, 91), and the right, where the fireplace now almost exclusively provides light, drawing in space the geometrical triangle from which the scene is ordered.

Oudry thus shifts the scenic moment, or more precisely concentrates it /// artificially : Fate on the left is still spanking the hostess, the innkeeper on the right is still busy with his antagonist, as when darkness reigned in the room in the background, the Cavern and Angelica have brought light, but in vain on the left, the Rappinière, right arm raised and index finger extended, pronounces the advent of law. There are three moments, of darkness, light and the return to order, condensed into one pregnant instant.

The stage space, now limited, contained, represents a symmetrical disorder : there are no longer two, but three groups of combatants, to which correspond three groups of spectators who frame them : the standardized scenographic model, which became generalized in the pictorial and theatrical representation of the Enlightenment, is now in place.

La Rappinière skewered by a goat

With Scarron, this model is only emerging. To the measured regulation of visibilities, Le Roman comique prefers the power of emergence from the " on n'y voit rien ". In the night fight, Fate is captured, sketched " encountering something peeling ". Similarly, in chapter 4, in the darkness of his home where he already imagines his wife is having a tryst with Fate, Rappinière encounters something sharp :

" As he left his room, he heard walking ahead of him, he followed the noise he heard for a while and, in the middle of a small gallery that led to Destin's room, he found himself so close to what he was following that he thought he was stepping on her heels. He thought of throwing himself on top of his wife, grabbing her and shouting: Ah whore ! His hands found nothing and, his feet meeting something, he gave his nose in the ground and felt something sharp being driven into his stomach. " (I, 4, 46.)

Thinking he's grabbing his wife, Rappinière gets skewered by a goat. Once again, we can't see : the uproar mimics a rape for laughs, a rape in reverse with nose and horns. The " something sharp " crystallizes what is not yet a scene, but will serve as a fulcrum for the deployment of visibilities, when " the maid, with a candle ", appears. An analysis of Martin's painting and Oudry's drawing would confirm the same process of emergence of the scenic device: in the compartment that occupies half of Martin's canvas, the visual effect is one of violent chiaroscuro contrast between the white nightgowns and the red half-light of the gallery. The figures form a homogeneous circle, in which the Rappinière is included, like Fate, above his wife, brandishing his sword. Oudry, on the other hand, distinguishes three planes: the scene itself, in which the Rappinière is one with the goat; around the scene, the spectators form a circle and, through this circle, delimit it; above the scene, finally, Fate appears with his sword, unifying the space as did the portrait on the back wall in the night fight. Once again, the distinction of the three planes allows for the amalgamation of three temporalities: the encounter with something sharp in the darkness, then the irruption of light that turns this encounter into a tableau, and finally the brandished sword that puts an end to the tumult: this hierarchy is not perceptible in Martin's composition. In Scarron's case, it's only in the making:

." ... everyone came to his aid at once : the servant, with a /// chandelle, la Rancune and le valet en chemises saleses, la Caverne en jupe fort méchante, le Destin l'épée à la main et mademoiselle de la Rappinière vienne la dernière et fut bien étonné, aussi bien que les autres, de trouver son mari tout furieux, lutterant contre une chèvre qui allaitait, dans la maison, les petits d'une chienne morte en couche. " (I, 4, 46.)

Scarron hesitates. At first, he describes a tumultuous, simultaneous arrival : " everyone came to his aid at the same time ". But in a second step, he hierarchizes this arrival, the enumeration of characters becoming a succession in time, and even a hierarchical gradation : " mademoiselle de la Rappinière came last " so she didn't come at the same time. Unlike Oudry, who makes Destiny the last to arrive, Scarron gives this role to La Rappinière's wife. She has the prerogative of the distanced gaze, which circumscribes and recognizes the scene, giving it signifying visibility. Scarron calls her " mademoiselle " : she's a woman of a certain rank, whose nobility obviously contrasts with what La Rappinière has taken her for.

Scarron doesn't, however, evoke Mademoiselle de la Rappinière's look. Not yet : there will be a whole semiology of the gaze in Le Roman comique, but later, in the second part. What's important here is first and foremost the succession of misunderstandings : the Rappinière has mistaken a goat for his wife ; but the goat itself has mistaken puppies for her kids. You never meet who you're supposed to meet.

II. La déconnue

The invisible lover

![Contes et nouvelles de Marguerite de Valois, reine de Navarre, mis en beau langage accommodé au goût de ce temps [...], Amsterdam, Georges Gallet, 1698, 1708, Versailles, Bibliothèque municipale centrale, F.A. in-8° E431e, engraving by Romeyn de Hooghe for the 43rd short story](/system/files/styles/crop_thumbnail/private/notices/007/haute_def/007672.jpg?h=9c202610&itok=B9MrBmai)

This adage could serve as the title of the first of the Spanish short stories embedded in le Roman comique, entitled " Histoire de l'amante invisible ". Strictly speaking, the short story is not by Scarron, but by Solorzano, whom he translates so it is not as a narrative invention, but as a fictional reference in Scarronian creation that it signifies.

Once again, it must be said that the fictional basis of " L'Amante invisible " is the observation that we see nothing. Dom Carlos falls in love with " la dame inconnue ", " la dame masquée ", " son amante invisible " (I, 9, 61-62), " la dame invisible ", " l'invisible " (p. 63) precisely because he cannot see her. In the first encounter in the church, it's his mind that pricks him, replacing the visual surprise of /// the inamoramento :

" ... dom Carlos remained as piqued by the unknown lady as if he had seen her face, so much power does the spirit have over those who have it. " (I, 9, 62.)

Dom Carlos is then attracted by a voice, which calls to him from behind a jealous :

" He approached the window, which was grilled, and recognized from the voice that it was his invisible lover " (ibid.).

Finally, the lover's invisibility completely disorients dom Carlos, paralyzes him, and creates amorous stupor :

" She withdrew as she finished these words, leaving dom Carlos with his mouth open and ready to reply, so surprised by the sudden declaration, so enamored of a person he could not see, and so embarrassed by this strange procedure and which could go to some deception that, without leaving a place, he was a great quarter of an hour making various judgments on so extraordinary an adventure. " (I, 9, 63-64.)

The lover's invisibility creates an imbalance. Dom Carlos made a spectacle of himself all over the city : " He did wonders with his person in public spectacles " ; he " dressed as well as he could and found himself with a quantity of other tyrants of the hearts in the church of gallantry " (I, 9, 60), " who mirrored themselves in their beautiful feathers like peacocks " (p. 61) ; he found himself " in all the barrier fights and all the ring races " ; he " made it seen by his black and white liveries that he was not in love " (ibid.). Scarron describes, not without humor, the peacock's parade, and the visual lure he holds out to the assembly of women, whom he makes see that he is to be married. The brilliance of the parade, however, clashes with the mask, then with the grille, and finally with the simulacrum of the other woman, hyper-visibility versus invisibility, the blind offer of a virile given-to-see versus the entrenched gaze of the invisible lover. Dom Carlos formulates this imbalance :

" for," he added, "you see me and know who I am, and I do not see you and do not know who you are. " (I, 9, 63.)

The narrative here implements a fundamental separation, constitutive of the scenic device. There is no stage without the implementation of a theatrical visiblity ; but this visibility, in the theater, and from there in the scenic devices that the novel imports, is a cleaved visibility. On the one hand, the spectator watches the stage without being seen, he is the invisible lover ; on the other, the actor produces spectacle, he gives to be seen, like don Carlos, but does not see the spectators, who, to use Diderot's formula, must remain " the ignored witnesses of the thing ".

The undifferentiated tumult of the " on n'y voit rien " is thus replaced by this cleavage : on one side the spectator, the invisible lover, establishes an overhanging but subtracted gaze, deploys the field of a gaze, which orders, arranges visibilities. It is she, the invisible one, who drives the narrative, arranges the encounters, orders the cunning. On the other hand, the actor, Dom Carlos, produces the visible, deploys the amorous parade, and lays out the traps and lures of the scopic. But these are only lures, and here, they lend themselves to laughter the scopic function is an induced effect of the field of the gaze it has no autonomy of its own it is a response, downstream, to the field of the gaze that has opened up upstream.

.Between the lover's gaze and don Carlos's given-to-see, the narrative interposes a mask, a grid, then an avalanche of masks. The whole story lies in this interposition, in this screen, which is the screen of representation.

A narrative model : Jambicque

Scarron is certainly translating here Los efectos que haze el Amor (The Effects that Love Produces), the third of the short stories in Solorzano's collection, Los Alivios de Casandra (The Entertainments of Casandra). /// Cassandre), published in Barcelona in 1640. The change in title is significant : the Spanish title focuses on the content of the narrative Scarron concentrates all the attention on the device.

.Solorzano is not, moreover, the first to exploit what constitutes a veritable narrative topos. In the 43rde short story of L'Heptaméron, Marguerite de Navarre recounts how the prudish Jambicque, having fallen in love with a gentleman, gives him masked appointments to preserve her reputation for wisdom and virtue, " having put on her low cornette and her nose touret ". The little merry-go-round lasts for some time, without the gentleman being able to guess who the lady is:

" Et continuerent longuement ceste vie, sans ce qu'il s'apperceust jamays qui elle estoit : dont il entraent en une grande fantaisye, pensant en luy-mesme qui se povoit estre ; car il ne pensoit poinct qu'il y avait femme au monde, qui ne voullut estre vue et aymée. "

Finally, driven by curiosity, he unknowingly marks Jambicque's back with a line of chalk, and runs to post himself in the bedroom of the princess with whom they are both staying :

" incontinant qu'elle fut partye, s'en va hastivement le gentil homme en la chambre de sa maistresse, et se tint aupres de la porte pour regarder le derriere des espaules de celles qui y entroient. Among other things, he saw Ceste Jambicque enter with such audacity that he feared to look at her like the others, being very sure that it couldn't be her. Mais, ainsy qu'elle se tournoit, advisa sa craye blanche, dont il fut si estonné, qu'à peyne povoit-il croire ce qu'il voyoit. " (Op. cit., pp. 505-506.)

With Marguerite de Navarre, the fall of the narrative is achieved by a return to a masculine mastery of the gaze. There's no schize : the masked woman is unmasked, turned ; it's from behind that Jambicque betrays and reveals herself. In the end, it's the one who was watching who is made visible.

Contre Jambicque, Urgande la déconnue

With Scarron, the invisible remains unknown : she must elicit another woman, Princess Porcia, endowed with a face and an identity, and refer to herself as this Porcia to put an end to the fiction. Of course, there are only two women for the deceived Dom Carlos, and these two women are really just Porcia masked and Porcia unmasked. But the magical power of the story lies in this fictional invisibility, which is maintained for as long as possible: in the end, and in the logic of fiction, which is also that of the heroic and marvellous models that Scarron solicits, Porcia is no more than a mirage created by the invisible. Witness his comparison of Porcia with the famous sorceress from Amadis des Gaules :

" Never had our Spaniard seen a better-looking person than this Urgande la déconnue. He was so delighted and so astonished at the same time that all the curtseys and steps he made as he gave her his hand to a nearby room where she let him in were as many bronchades. " (I, 9, 70.)

Once again, the misstep, the stumble, the fall mean that we can't see a thing, even in the brightest moment of the fairy-tale scenography organized by Porcia to put dom Carlos to the test. Scarron intervenes in the narrative, referring to Porcia as " cette Urgande la déconnue ", Urganda la Desconocida, who in Amadis rules over la Insola no Hallada, the untraceable island, the invisible island. Desconocida translates today as unrecognizable, or unknown.

Urganda is a female Proteus. She introduces herself as follows when she first appears before Gandales, Amadis 's mentor:

" My name is Vrgande la Descogneuë : & à fin que me coignoissez vne autre fois, regardez moy biê à présent. At the moment she who showed herself in Gandales beautiful, young & /// fresche, comme de dix huit ans, se fait tant vieille & si cassée, qu'il s'estônoit comme elle pouuoit se tenir à cheual. If he was then amazed, you may think so: but when she was a little in this shape, she drew some oil from the box she was carrying, and rubbed herself, and soon regained her first shape, saying to Gãdales: Well, what do you think? in your opinion, could you find me beyond my will hereafter, no matter how diligently you try? Pourtant ne vous en donnez peine : car quãt tous les viuans l'entreprêdroient ilz y perdroiêt leurs pas si bon ne me sembloit. " (Amadis de Gaule, translation-adaptation by Nicolas Herberay des Essarts, 1540-1548, F°XVII.)

At the moment when the invisible lover reveals herself to Dom Carlos under her true face of Porcia, by which the latter virtuously misrecognizes her, i.e., repels her as not being the invisible lover to whom he has sworn fidelity, Scarron tells us that Porcia is an Urgande la déconnue, meaning not only that she is misrecognized by Dom Carlos, but that she masters a perpetual misrecognition. Such was Urgande's fame that Cervantes places at the head of his first part of the Quichotte, after the prologue and by way of dedication, ten poems in versos de cabo rato (with the last syllable missing) supposedly written by her. Among them this advice :

" Think it's very imbé[cile]

Under glass roof very fra[gile]

To take a stone in [hand]

To throw it on the voi[sin]. "

This glass roof is the ancestor of the grid, the veil, the screen of stage performance.

The invisible lover on stage

Once the " Histoire de l'amante invisible " is completed, Ragotin, who is supposed to have recounted it before the assembly of actors, boasts that he can transpose it to the stage :

" Destiny told him that the story he had told was very pleasant, but that it was not good for the theater. My mother was a goddaughter of the poet Garnier and I, who am speaking to you, still have his writing case at home. Destiny told him that the poet Garnier himself would not come to his honor. And what do you find so difficult ? asked Ragotin. " (I, 10, 80.)

And the quarrel drags on until suppertime. Underneath its comical exterior, the question is also serious : we have tried to show that it is precisely the modern stage device, with its division of the given to be seen and the looked at, with its screen, that emerges as the hegemonic device of representation and is put into representation in this fiction. Literary history, moreover, vindicates Ragotin against Destiny, with a whole theatrical production exploiting the motif of the invisible lady : it's La Belle invisible ou la constance éprouvée by Le Métel de Boisrobert (1656), L'Amante invisible by Nanteuil (1673), L'Esprit follet ou La Dame invisible by Lebreton de Hauteroche (1684) and finally, closest to Solorzano and Scarron, Don Carlos ou l'amante invisible, an opera given in Paris in 1778.

The meeting of Garigues and Léonore

The fictional integration of the new scenic device that the " Histoire de l'amante invisible " extrapolates from Solorzano takes place a few chapters later, in the " Histoire de Destin et de mademoiselle de l'Etoile ", which unlike the Spanish short stories is Scarron's own invention. Garigues' first encounter with Léonore is a failed rape scene in the Roman vineyards, which the narrator (Garigues-Le Destin) observes, then interrupts :

" I saw at the bend in an alley two fairly well-dressed women, whom two young Frenchmen had stopped and wouldn't let pass unless the younger one lifted a veil that covered her face. One of these Frenchmen, who appeared /// be the master of the other, was even insolent enough to uncover his face by force " (I, 13, 99).

The narration parallels the two women's halting journey with the veil that stops the gaze on Leonore's face. Getting past Saldagne, the aggressor, means Leonore has to discover his face. Brutality and rape are foreshadowed, signified first by the interposition on the path, then by the torn veil. The arrangement of the figures in the space is thus linked to both a scopic issue (discovering the face of the desired woman, reveling in the sight of her, the gift of sight she can offer) and a symbolic transgression (the chivalric, courteous respect due to women). This double articulation, scopic and symbolic, is symptomatic of a deployment of the scenic device, which had hitherto only emerged. It translates into the dramatization of the lifting of the veil:

Scopic and symbolic linkage is symptomatic of the deployment of a scenic device that had hitherto only emerged.

" After this, as if to reward me for the service I had rendered her, she added that having prevented her daughter from being seen in spite of herself, it was only fair that I should see her willingly. Lift your veil, Leonore, so that Monsieur may know that we are not altogether unworthy of the honor he has bestowed on us by protecting us. No sooner had she finished speaking than her daughter raised her veil, or rather dazzled me. I've never seen anything more beautiful. She looked up at me two or three times, as if on the sly, and as she met mine, her face flushed red, making her more beautiful than an angel. I saw that the mother was extremely fond of her, for she seemed to share in the pleasure I took in looking at her daughter."(I, 13, 99-100.)

You'd think that lifting the veil would abolish the schize of the eye and the gaze and homogenize the field : it doesn't. The lifting is theatricalized as an eroticization of the threshold. It dazzles Garigues, i.e., Leonore's eye blinds him, and keeps him unaware of the gaze that doesn't see. Léonore's eye rests on Garigues " as if by stealth " that is, as if he were still crossing an obstacle to get to him, as if a virtual veil had replaced the one that had been lifted. Leonore blushes this is yet another way of becoming unrecognizable " more beautiful than an angel ", she interposes between her person and that of her lover the screen of a celestial, blinding vision, which keeps her more than ever in invisibility.

Garigues never ceases to ignore Léonore. When his host invites him to dine at his mother's, he first insists on his blindness: " J'étais si interdit que je ne voyais goutte " (p. 101). The celestial vision that imposes itself on him prevents him from recognizing the person of Leonore, whom he does not greet :

" Finally, mind and sight returned to me and I saw Leonore more beautiful and charming than I had yet seen her, but I had no assurance of greeting her. " (Ibid.)

Without greeting, there is no recognition: paralyzed, stupefied (" I was always the same stupid "), the lover experiences scopic neantization, which perpetuates the screen of representation and the schize of eye and gaze, even when the field seems free for sight : " I did nothing with assurance but look incessantly at Leonore. I think she was annoyed by this and, to punish me, she always had her eyes downcast." " (P. 102.)

The problem of Leonore's identity

The device then swarms throughout the narrative : Leonore's identity remains mysterious until the end daughter of a clandestine marriage, she would have to be recognized by her father. This recognition is only possible by presenting her father with her own portrait, the image of which will prove her resemblance to his daughter, and possession of which will legitimize her filiation. But the portrait stolen by La Rappinière (I, 18, 156; II, 15, 292), the father still away /// further afield, first in Holland, then in England, delay this recognition indefinitely. The utopian scene of the portrait's presentation to the father constitutes the fiction's horizon of expectation through it, the system of visibilities could close in on itself, putting an end to the game of misrecognitions through the mise en abyme of recognition in the portrait there would now be only one image, only one filiation and only one law, of the father of course.

Garigues and Mlle de Léri : generalization of misrecognition

Léonore is thus another Porcia, another Urgande la déconnue : she delays, she fails to gain recognition she derives her appeal from this constantly renewed misrecognition. In the same way, in the story of Verville's love affairs, Garigues' encounter with Mlle de Léri, Saldagne's sister, whom he is given to understand as a "madame Madelon", is based on the same misunderstanding. Garigues, warned, announces the schize to the woman who is given to him, by force, as a companion during Verville and Mlle de Saldagne's clandestine rendezvous in his brother's garden:

" There are girls in Paris," I interrupted, "whose marks I'd be delighted to wear ; but there are also some I wouldn't want to even consider, lest I have bad dreams. " (I, 15, 123.)

On the one hand, Garigues is ready to wear the marks, i.e., the colors, the insignia of the woman he would love, to make himself the image of his Lady, to abyss himself in scopic neantization, to figure the schize through these marks he would wear On the other hand, he refuses to look into the face of the one who may be ugly, as if to protect himself from a possible nightmare vision, from the threat of scopic abjection, as if to interpose the screen of a protective cut. In both cases, it's a matter of maintaining ignorance, of oneself under the marks or of the other under the veil: to the simulacrum of " madame Madelon ", Garigues will oppose the simulacrum of the Bas-Breton valet dispatched in broad daylight to the ladies, " ce gros sot ", " notre lourdaud " (p. 124), shielding Garigues' invisible face, which is redoubled, in the frame story, by the plaster on Destiny's face, supposed to protect him from Saldagne's vengeful fury.

.III. Recognition

The meeting in Nevers

While in Le Roman comique a generalized economy of misrecognition is established, which is no longer exactly that of liminal tumult and disordered invisibility, but maintains visibility in a cleavage that prohibits the fulfillment of the gaze, the meeting in Nevers of Garigues and Léonore with his mother introduces an upheaval that is not only of the order of narrative peripety, but engages the entire semiology of novelistic representation.

The two women stroll across the " great stone bridge that crosses the Loire River " (I, 18, 147) ; Garigues arrives in the opposite direction, also strolling :

" I greeted them without looking at them as I passed by them and strolled along the bridge for some time, thinking of my unfortunate fortune and more often of my love. I was fairly well dressed, as is necessary for those whose condition cannot excuse a bad habit. " (P. 148.)

On the surface, it's always the same visual misunderstanding that presides over the encounter. But the brilliance of good looks has changed sides : while Mlle de la Boissière, Léonore's mother, is now ruined and ill, Garigues has put on his bright clothes, parading his figure to make up for a failing condition, in a strategy that prefigures that of Marivaux's Marianne. Garigues is not dazzled absorbed in himself, he neglects to look at two women who do not form a tableau on the bridge on the contrary, it is he who is recognized : " ... I heard said half aloud : /// As far as I'm concerned, I'd believe it was him if he hadn't died" (Ibid.). Never mind this false news of the young man's death during the Parma war Garigues' ghost, the Garigues guaranteed by the scopic game of misrecognition, acts as a screen for a moment before dissipating before the solar appearance of the one who is to become Destiny.

The narrator then dwells at length on the complacency towards him of the beleaguered Mlle de la Boissière. Léonore's face is her last card : " the state she was in did not allow her [...] to make me a bad face " (p. 149) ; " the girl appeared to me with a face as sad as I had found her cheerful a moment before " (ibid.) ; " I was no longer that odious man who had been refused the door into Rome and for whom Leonore was not visible " (p. 150) ; " Leonore appeared to me that day dressed with more care " (p. 151). Exposed, Léonore is the object of recognition, which does not resolve the symbolic misrecognition of the father but, on the imaginary level, lifts the scenic screen, puts an end to the schize :

" She came to love me as much as I loved her ; and you may well have recognized, in the time you've been seeing each other, that this reciprocal love is not yet diminished. What ! interrupted Angélique ; mademoiselle de l'Étoile is then Léonore ? " (Ibid.)

Narrative recognition puts an end to fictional " on n'y voit rien ". It fixes the figures, assigning them positions and identities, but by the same token puts an end to the scenic game, i.e. both to the effects of the novel scene in narrative and, in fiction, to the floating status of actors temporarily borrowed by the protagonists.

Ragotin and Roquebrune fall off their horses

More precisely, the passage from misrecognition to recognition completes the scene : it sets its rules, it stabilizes its play of visibilities. The adventure, the accident, the occasion, the encounter will henceforth take place in a space around which the spectators have been arranged. Replacing the pre-scenic "you can't see a thing", the "given to be seen" will serve as a means of recognition, for a risk-free show. The establishment of this new economy is very clear in the double scene in which Ragotin gets into the saddle sitting on his rifle, then Roquebrune, performing the same exercise with the same clumsiness, loses his shoes :

" Ragotin's accident hadn't made anyone laugh, because of the fear they'd had that he'd hurt himself ; but Roquebrune's was accompanied by great bursts of laughter that were made in the carriages. " (I, 20, 164.)

Contrary to the tumultuous episodes at the beginning of the novel, this double fall is painted in the open air and in public, " in view of the carriages that had stopped to rescue him or rather to have the pleasure ". The /// The scene is thus naturally ordered, with its restricted space delimited by the stopped carriages. The first time, there's a real fear of an accident: something of the anguish of fictional invisibility remains. The second time, the show is purely gratuitous, and can trigger general laughter. It's a tried-and-tested device.

List of illustrations :

Fig. 1 : Jean Baptiste Oudry, La Rancune en brancard abbatu dans un bourbier, in Vingt-six scènes piquantes du Roman comique de Scarron, Paris, Desnos [1760?], copperplate engraving, Versailles, Bibliothèque municipale centrale, Rés. J-58

Fig. 2 : Pierre-Denis Martin, L'Enlèvement du curé de Domfront, 1720, oil on canvas, 86x116 cm, Le Mans, Musée de Tessé

Fig. 3 : Jean Baptiste Oudry, Ragotin est renversé dans la boue, in Vingt-six scènes piquantes du Roman comique de Scarron, Paris, Desnos [1760?], copperplate engraving, Versailles, Bibliothèque municipale centrale, Rés. J-58

Fig. 4 : Pierre-Denis Martin, Combat de nuit pour le mot de cocu, 1720, oil on canvas, 85x114 cm, Le Mans, Musée de Tessé

Fig. 5 : Jean-Baptiste Oudry, Combat dans l'hôtellerie pour le mot de cocu. La Rappinière puts an end to the fight, black ink, gray and black wash, blue paper, black stone, brush, signed and dated lower left " JB. Oudry 1727 ", Paris, Musée du Louvre, RF1689

Fig. 6 : Pierre-Denis Martin, La Rappinière skewered by a goat and la Rancune spills her pot on her bedfellow, 1720, oil on canvas, 85x114 cm, Le Mans, Musée de Tessé

Fig. 7 : Jean-Baptiste Oudry, Le Destin tombe sur la Rappinière embroché par une chèvre, black ink, gray and black wash, blue paper, pierre noire, brush, signed and dated lower left " JB. Oudry 1727 ", Paris, Musée du Louvre, RF1686

Fig. 8 : Contes et nouvelles de Marguerite de Valois, reine de Navarre, mis en beau langage accommodé au goût de ce temps [...], Amsterdam, Georges Gallet, 1698, 1708, Versailles, Bibliothèque municipale centrale, F.A. in-8° E431e, engraving by Romeyn de Hooghe for the 43rd short story.

Fig. 9 : Jean-Baptiste Joseph Pater, Ragotin on horseback with his rifle, 1729-1732, oil on canvas, 28.7x38.3 cm, Berlin, Nouveau Palais de Sans-Souci.

Fig. 10 : Jean-Baptiste Joseph Pater, Le Poète Roquebrune perd ses chausses, 1729-1732, oil on canvas, 28.7x38.3 cm, Berlin, Nouveau Palais de Sans-Souci.

///Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « On n’y voit rien : l’invisibilité fictionnelle à l’épreuve de la scène dans Le Roman comique », Fictions de la rencontre : Le Roman comique de Scrarron, dir. S. Lojkine et P. Ronzeaud, Presses de l’Université de Provence, « Textuelles », 2011, p. 157-170.

Fiction, illustration, peinture

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Fiction, illustration, peinture

La scène de roman

La scène de roman : introduction

Renaud dans le jardin d’Armide

Rastignac chez Mme de Restaud

Gilberte derrière les aubépines

La poignée de porte de tante Berthe

La double aporie du topos

Illustrer la fiction

Molière, une parole débordée

Marillier, l’appel du mièvre

On n'y voit rien

Illustrations de l'utopie au XVIIIe siècle

Le temps des images

Du conte au roman graphique

Déconstruire l’illustration

Régimes de la représentation dans la gravure d’illustration classique

Penser la fiction depuis la peinture

Une sémiologie du décalage : Loth à la scène

Introduction à la scène comme dispositif : Paolo et Francesca

La main tendue, le regard démasqué

De Silène molesté à la chair blanche des nymphes

Chambres de la représentation

L'intimité de Gertrude

Brutalités invisibles

Parodie et pastiche de Poe et de Conan Doyle dans Le Mystère de la chambre jaune de Gaston Leroux

Le dispositif de la chambre double dans Les Démons de Dostoïevski

Scène pour voir et chambre des brutalités

La Princesse de Clèves

L’invention de la scène dans le roman français

La canne des Indes

L'aveu

La princesse, la religieuse et l'idiot

Richardson

Entre scandale et leurre

Introduction aux Lettres angloises, ou histoire de miss Clarisse Harlove, par Samuel Richardson