The engravings created by Gustave Doré for the Book of Genesis help us understand how he illustrated the Bible.

The distribution of engravings

While the first edition of December 1865 included only 27 engravings for Genesis, the 1866 edition, which serves as a reference, adds 3 on "an additional table" resulting in a total of 30. To these engravings must be added 10 drawings published in 1868 in the volume La Sainte Bible. Photographies, which were not engraved, but show the creativity of Gustave Doré, who thus created 40 drawings for Genesis.

Distribution of images in relation to text

The engravings are published following the order of the biblical text, but they are never opposite the corresponding verses. The "Creation of Light" is placed at the head of the volume, and it is the creation of Eve that opens Genesis; the other engravings follow each other every 6 pages, while the chapters of the text unfold more rapidly: thus the last plate of the story of Joseph is found, in the 1866 edition, p. 196, in chapter XIX of the Book of Numbers, a long way from that of Genesis. The engravings do not, therefore, strictly speaking illustrate the text opposite: they construct their own itinerary, followed but autonomous, in the book.

The engravings are divided according to the chapters of Genesis: 10 engravings and 3 supplements concern the first 11 chapters, from Creation to the Tower of Babel; then the next 10 engravings, with 3 supplements, concern the Abraham-Isaac cycle; finally 10 others with 4 supplements, are dedicated to the Jacob-Joseph cycle.

Episode selection

For Gustave Doré it wasn't a matter of systematically putting the Bible into pictures, but of highlighting a few passages through his engravings. He follows the main chapters and their heroes, favoring certain scenes and rejecting others in a very personal way.

Origins of the world and humanity

The representation of creation is limited to the creation of light.

The part about Adam and Eve is reduced to Eve's creation and their expulsion from paradise, without mentioning temptation or the fall.

But Abel and Cain are very much present through their offerings and Abel's murder.

Noah is virtually absent: in 1865, he is reduced to the stranded Ark; in 1866, Doré adds the curse of Ham. But neither the animals on the Ark, nor the rainbow of the Covenant, are depicted in images. The Tower of Babel, on the other hand, has its rightful place.

The Patriarchs

Gustave Doré focuses on the Patriarchs: Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and Joseph.

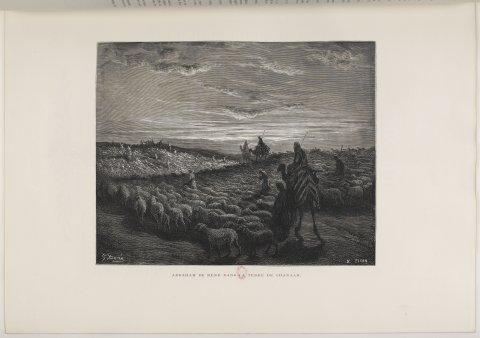

The Abraham cycle centers on Abraham's vocation, as he receives the promise of the land of Canaan, which he is to share with Lot. The angels' visit promises him offspring: Hagar, with her illegitimate offspring, is expelled. Isaac's sacrifice is somewhat forgotten. Eliezer goes to find a wife for Isaac, Rebecca, who is well received.

The final image concerns Sara's burial, an episode that is virtually never depicted in pictures. Gustave Doré, through his composition, establishes an unprecedented relationship between the two Testaments, between Sara laid in the tomb and the women in front of Christ's empty tomb.

The last image concerns the burial of Sara, an episode that has hardly ever been depicted in pictures.

Jacob and Joseph

For the Jacob cycle, the choices are more surprising. We have to wait until the 1866 edition to see Jacob's blessing by his father, the most famous episode of the cycle in iconographic tradition. Doré also adds the final reconciliation between Jacob and Esau, thus privileging the relationship between the two brothers: Jacob steals the blessing due to Esau, prays and is finally reconciled with him.

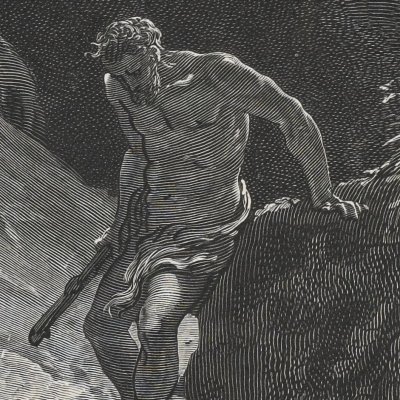

Jacob also dreams that he is privileged by God: this is Jacob's dream, in which a celestial ladder appears to him, an episode which for him is part of a long iconographic tradition. Here, Doré makes masterful use of his art of light and shadow, which he developed with the technique of standing woodcut: the effect of light surreally shrouding the landscape that surrounds the character is repeated in the following episodes of the departure to his uncle Laban's, where he meets Rachel, the night prayer, and the struggle with the angel of God.

Jacob also dreams that he is privileged by God: this is the dream of Jacob, in which he sees a heavenly ladder, an episode that is part of a long iconographic tradition.

For the episode in which Joseph, Jacob's favorite son, is sold by his brothers to nomads who will take him to Egypt, Doré once again departs from iconographic tradition by depicting neither, or not directly, Joseph thrown into a well, nor Joseph's tunic, falsely stained with blood, returned to Jacob.

For the episode in which Joseph, Jacob's favorite son, is sold by his brothers to nomads who will take him to Egypt, Doré again departs from iconographic tradition by not depicting Joseph thrown into a well: he also produced a drawing depicting the presentation to Jacob of Joseph's falsely blood-stained tunic, but did not have it engraved.

For the Egyptian episodes that follow, the interpretation of Pharaoh's dreams, the reunion of Joseph, now powerful, with his brothers, and the coming of Jacob, Doré constructed settings hitherto unseen in biblical iconography, which he borrowed from the archaeological descriptions of Egypt made during Napoleon's campaign.

Modes of representation

The taste for the tragic

Biblical illustration comes under the heading of history painting, and as such a whole classical iconography developed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries identifying the biblical episodes represented with scenes of tragedy, implying a certain framing of the action, a condensation of narrative time, a system of looks ensuring the tragic effect with theatrical means.

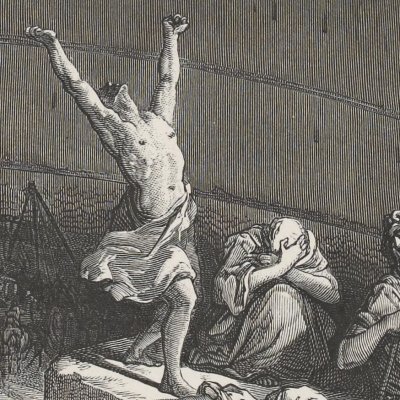

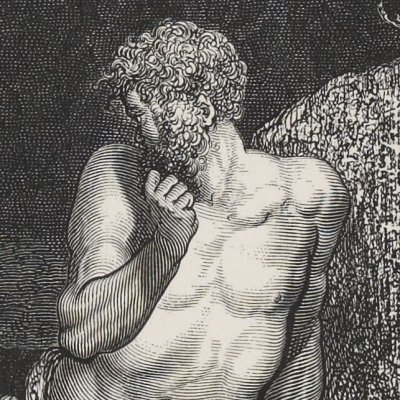

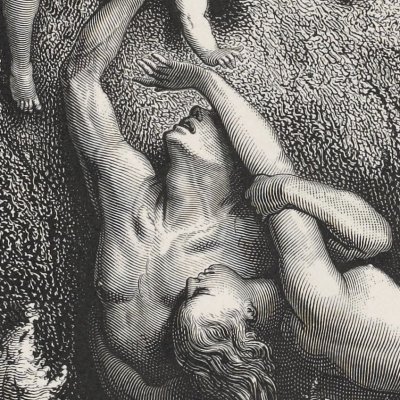

Classical tragedy is no longer necessarily the reference model for Gustave Doré, who produces tragedy with other means, plunging his characters into vast dreamlike landscapes drowned in shadow or, on the contrary, bathed in a strangely disquieting light. For Adam and Eve expelled from Paradise, for example, Doré hesitated between two drawings, which do not accord the same respective place to the man and woman, and thus do not focus the tragedy on the same character: but in both cases, the personal expression of the figure in despair produces its effect by immersing the viewer in a wordless nightmare, far removed from the theatrical stage and its declamations.

.

The tragic scene is an autonomous unit, deriving its coherence from respect for the unities of place, time and action. Gustave Doré, for his part, does not refrain from creating two successive images and developing the tragic in this succession. In Cain and Abel, for example, he depicts first the offerings to God, then the completed murder, not simply as milestones of a narrative, but above all as a gradual darkening, and a worsening of the solitude of Cain, whose posture in front of his slain brother repeats and accentuates that in front of his sacrifice: jealousy has not only caused the murder; it has in a way anticipated its postures and device.

In the Abraham cycle, Doré resorts to the same play of cause and effect with his two engravings concerning Hagar, first driven away by Abraham, then abandoned in the desert, with the same effect of repetition or echo, of darkening and dreamlike precipitation towards death.

Abraham's sacrifice of Isaac is a famous and customary depiction, abundantly exploited by classical theatrical tragic iconography, to which it offers all the ingredients of the scene: constricted space of the representation, at the top of Mount Moriah, dramatic suspense of Abraham's knife raised against his son, but stopped by the angel, mixed expressions of horror, submission, even revolt by the protagonists.

But Doré was looking for other effects, and the tragic for him lay elsewhere. He executed the drawing of the Sacrifice but did not retain the image for engraving. Instead, he chose Isaac carrying the sacrificial wood, internalizing the tragedy.

The same goes for the story of Joseph: once sold by his brothers, we wait for the scene where they bring a bloody robe to Jacob to confirm his son's death. Doré did produce the drawing, but did not retain it for the engraving.

With the Deluge, the tragic becomes morbid: the event takes on great prominence, as it is given two successive engravings, "Le Déluge" and a "Scène du Déluge", which is a kind of close-up from the previous image : Doré does not proceed by narrative succession, but by intensification.

The two images are strong, sinister and despairing, and on the third, entitled "Noah sends a dove to earth", we see only the Ark, above the corpses: the hero is barely sketched at a window.

An open, mysterious space

If the tragic refers to Doré's romanticism, the landscapes also invite it. These are vast landscapes, which open up to dreams and whose infinity calls for meditation.

"He needs [...] steep mountains. Mysterious faraway places. Strange creatures, dragons or otherwise. Twisted trees. Natural cataclysms. Generally speaking, Gustave Doré's images appear overloaded with detail. But these details never detract from the overall composition. There's a kind of balance in the unstable and harmony in the excessive1."

Several scenes allow you to build large spaces without limits. Some are published in "landscape" format, such as "Abraham entering Canaan", which doesn't help when handling the book! For "Jacob's fight with the angel", Delacroix's forest is replaced by a wide-open landscape. And for "Abraham and the three angels", Doré made two drawings, one where the divinity is at the center of the infinity, and the other where everything is tightened on the event of the visit.

The taste for theatricalityé

The tragic effect developed by Gustave Doré thus differs from classical tragedy and its theatrical stage model. This does not mean, however, that Doré renounced theatricality. He has even been criticized for an overemphasized taste for dramatic intensity in his compositions.

How can we define this theatricality, which is not that of classical tragedy, and which is not structured, framed by the enclosed, or semi-enclosed, space of the theatrical stage?

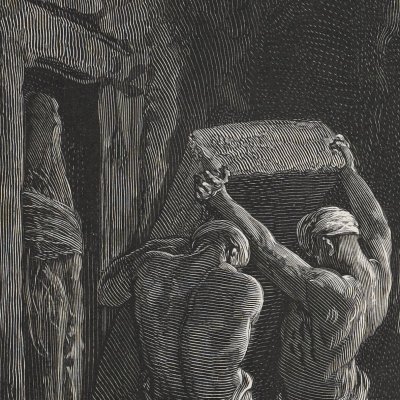

First and foremost, it's a theatricality of crushing. We see this clearly in the scene of Abel's murder, in that of Hagar in the desert, or in the episode of the Tower of Babel, where man appears crushed by the tower he magnifies.

It's a theatricality of crushing.

This is then a theatricality of illumination: theatrical scenes are built on strong contrasts between celestial light and disquieting darkness, with powerful chiaroscuro effects. In "Adam et Eve chassés", divine light illuminates the whole scene against the light, turning every tree branch into a danger for the couple. In "Jacob Goes to Egypt" and even more so in "Jacob's Prayer", chiaroscuro is brought to maximum effect.

In "Cain and Abel offering their sacrifices", the character of Cain turning back to Abel to look at him jealously is particularly enchanting and disturbing.

Sometimes, Doré seems to sacrifice to classical theatricality: set against a backdrop of flames and smoke, the protagonists of "Loth's Flight" seem to take on the grandiloquent attitudes of great tragedy tirades. Yet on closer inspection, it is essentially Lot's wife who adopts a theatrical posture: frozen like a mute salt statue, she represents the dead world from which Lot and his daughters are escaping. To paint the old world, Doré resorts to the old modalities of the tragic: but Loth and his two daughters fleeing in the foreground repeat the composition of "Adam and Eve driven out", with the same tragic effect, drowned in a vast nightmare landscape and internalized in the figures' expressions.

It's as if, each time, Doré gave himself the choice of theatricality, only to reject it. For Rebekah and Eliezer's encounter at the well, he produced two drawings. The more theatrical of the two was rejected. The same goes for the two drawings of Joseph being recognized by his brothers. Sometimes, even when the biblical story mobilizes real theatrical resources, Gustave Doré refuses to exploit them: he treats the "Blessing of Jacob by Isaac" as if there were no trickery involved. The meeting of Jacob and Rachel ("Jacob at Laban's"), gave rise to three images: none of them plays on the emotion of love.

Between romanticism and realism

Despite this detachment, this refusal of too easy effects, Émile Zola criticized him as "closer to the Romantics than to contemporary artists2 ".

But Gustave Doré, supported by Théophile Gautier, willingly placed himself in a second-generation Romantic movement, one that had rediscovered Rembrandt and his chiaroscuro, one that cultivated the imagination, and one that remained very much alive in England: Doré's success across the Channel and then across the Atlantic, including for his pictorial productions, is largely explained by this particularity.

But the romanticism of chiaroscuro does not exclude a certain realism of environments. Doré is not interested in social milieus and the types they produce, but in natural and urban environments; he is attentive to the landscapes, architectures and costumes in which scenes are set. Gone are the days in the nineteenth century when the artist portrayed biblical characters dressed like his contemporaries, surrounded by the factories, plants and vegetation of his homeland. Now it's a matter of inventing a biblical milieu, a local color, the settings and clothing that a few decades later will be those of the first peplums.

So, for the construction of the Tower of Babel, Doré intends to technically recreate an ancient building site from Babylonian times (even if he makes the mistake of placing horses there...). For Rebecca's arrival, he designed a caravan like the orientalist painters of the time could paint in Morocco or Algiers, Egypt or Jaffa. For Joseph, living in the heart of Pharaonic Egypt, he called up the engravings and early photographs arriving from Karnak, Louksor or Thebes. The scene depicting Joseph interpreting the king's dreams takes place in a temple with lotus columns, whose back wall is carved with bas-reliefs: Doré stuck as closely as possible to the images he received from Egypt. He produced two drawings, similar except for the back wall: for the engraving, he chose the one in which he drew the ankh, a symbol similar to the Latin cross, which enabled him to inscribe the Christian genealogy even in the most apparently faithful archaeological reproduction. For the scene of "Joseph recognized by his brothers", Doré took an archaeological drawing of Karnak as his setting and décor.

Doré never went to the Near East or Egypt. Nor was he the initiator of this new way of depicting biblical times: shortly before him, the engraver and geographer Otto Delitsch (Illustrirte Pracht-Bibel, 1862) had introduced this concern for the environment. Doré sometimes imitated him, for the Deluge for example, with its clusters of men and women trying to escape death, and above all with its Ark resting on dry land. But he also imitates Jules Schnorr de Carolsfeld (Die Bible in Bildern, Leipzig, Wigand, 1860) who, only a few years earlier, still resorted, in the neo-classical vein, to elegant stylization: we find the inspiration in "The Creation of Eve", "The Arrival of Rebekah" or "The Blessing of Isaac".

Prehistory

It's not just a question of greater fidelity to history, but of a revolution in the way we think of history, no longer as a narrative, but as a world and a milieu.

Acknowledging environments allows Doré to go beyond history. Prehistory was emerging at the time. Linné and especially Buffon, by moving back the date of the earth's creation, had begun to think of the world before men, and men before the invention of writing. From 1838 to 1841, Boucher de Perthes, considered one of the inventors of Prehistory, published De la création: essai sur l'origine et la progression des êtres, followed, from 1847 to 1864, by Antiquités celtiques et antédiluviennes. L'Univers avant les hommes, by Pierre Boitard, was published in 1861, with numerous illustrations by the author, including depictions of prehistoric animals.

When Doré drew the Deluge, he set it in this environment, with its disproportionate vegetation and fantastic animals. The drawing chosen for the Deluge engraving shows a man and his horse; the other, very close in composition, enhances an imaginary monster: did Doré finally eliminate the depiction of antediluvian fauna that didn't conform to the dogma of the Creation of the world in 6 days?

Did Doré finally eliminate the depiction of antediluvian fauna that didn't conform to the dogma of the Creation of the world in 6 days?

Notes

Alix Paré, Fantastique Gustave Doré, Éditions du Chêne, 2021, p. 295.

Émile Zola, Écrits sur l'art, ed. Jean-Pierre Leduc-Adine, Gallimard, Tel, 1991, p. 55.

Illustrer la Bible

Dossier dirigé par Serge Ceruti depuis 2023