We know the situation: all over France, the literary streams in lycées are emptying out, and in universities, student numbers in humanities departments, after a sharp fall, are stagnating or continuing to decline. When questioned, students often explain their presence in these departments as a last resort, because they were unable to enroll in a more selective, more prestigious and more promising field of study. The teaching profession no longer appeals, and a few years later, these same students resign themselves to it rather than rush into it.

.This is clearly a phenomenon of society, and even of civilization: literature has lost the symbolic prestige that once assigned it a central position in the educational system, making the schoolteacher, the man of the book, the lever of social ascent, and mastery of the beautiful language - the necessary condition for a political or entrepreneurial career. There was no ascendancy over men without a mastery of letters; no social pre-eminence without the magistracy of culture.

.The first question we are asked today, then, not without brutality, is that of the utility of literature, not a moral or democratic utility1 pleaded in the form of lamentations and regrets, but a utility, a function that we might see in post-modern civilization. Even more radically, is it possible today to think of a society without literature and, which is not exactly the same thing, without books? From this first question follows a second, even more essential one: what do we mean by literature? In other words, if our civilization is losing something, what exactly is it losing? Is it an object it's losing (texts, books, culture), or a certain relationship to that object? This raises a third question, which reverses the previous one: can we transform this relationship to the object through our teaching? No longer lamenting a loss, but, shifting paradigm, grasping, accompanying an emergence?

And to begin with, let's put things at their worst: suppose a society that sought to get rid, systematically, of books, to eradicate literature. This is the hypothesis of Ray Bradbury's short novel, Fahrenheit 451, published in 1953: "451 degrees Fahrenheit - the temperature at which the paper of a book catches fire and burns2".

Bradbury imagines a society in which firefighters would be the linchpin, firefighters charged not with putting out fires, but with burning books and homes where there were any left. The novel's hero, Guy Montag, is one of these firemen. While his wife, Mildred, lives and breathes television, installed on three and soon four screens in the living room, Montag meets a number of people - an eccentric young neighbor, Clarisse McClellan, and an old professor, Faber - who make him question the wisdom of his job. Montag starts stealing books, trying to read them. Suspected by his captain, Beatty, and denounced by a friend of his wife, Montag has to burn down his house himself. He then kills his captain and runs out of town, where he joins other outsiders, while the war, announced as imminent from the beginning of the novel, causes the general bombardment of the world he has left.

.I. Perverse structure of antimodernity

Published at the height of the Cold War, Fahrenheit 451 reads primarily as a denunciation of totalitarian regimes. A 1977 French edition3, aimed at young audiences, drives the point home: the novel is followed by an unsigned educational dossier; yes, books have been burned in the history of the world. The burning of books ordered by Chi-hoang-ti, the first of the Tsin emperors, in 214 B.C., the burning of the Library of Alexandria in 641, an "auto-da-fé of documents in Chile just four years ago" are mentioned, but not a word about the literature designated as Jewish or dissident and burned by the Nazis in the spring of 1933 all over Germany. The death of books is distant in time and space. The discourse is reassuring: the rise of civilization is powerful, universal, inexorable. First, writing "preserved and exchanged information", "perpetuating" civilization. Then publishing "enabled the creation of data banks (libraries) and the spread of ideas and knowledge throughout the world". Finally, the telephone, telecommunication satellites, television and the computer ensured optimum security for this information:

."Finally, the complexity of communication networks, the dispersion and multitude of data banks - whether book-based or electronic - mean that it would be impossible for a dictator, such as the one described in Ray Bradbury's novel, to wipe out every trace of knowledge on the surface of the globe. The only thing such a dictator could do, momentarily, would be to control the spread of knowledge in a given region. This is what history shows us every day." (Last page of the dossier)

So, our young audience is reassured, ready to learn a lesson from literature: let's remain vigilant in the face of a political danger, dictatorship, which will certainly never strike down humanity, but can momentarily disrupt, regionally, the global system for disseminating human knowledge. To guard against this risk, the dossier promotes the development of communication techniques, one of whose flagships is the television screen.

Or, in Bradbury's novel, this screen, and in particular the famous fourth wall screen that Mildred desires to perfect and close in on itself her TV lounge, is the symbol of dictatorship, the means of gently triumphing over books and reading4. Bradbury's opposition is not, as in the dossier, between dictatorship and progress, but between a civilization of books and a civilization of television, between a literary heritage and a technological modernity. Montag's revolt is not a progressive emancipation; it's an anti-modern revolt.

With the counter-intuitive teaching it claims to draw from the novel, the dossier that follows it paradoxically points to its essential malaise, and at the same time its visionary significance: the books that are burned signal as scandal in the fight for Enlightenment; one thinks of the Dictionnaire philosophique burned over the body of the Chevalier de la Barre in Abbeville in 1766. The stakes seem clear to us, in a game whose right side is all but designated to us: on one side, tolerance, freedom of conscience, justice - books, literature are on that side; on the other, superstition, obscurantism, mockery of justice - that's the side of the pyre to books.

But the books Bradbury's firefighters burn don't exactly send the reader this differential play, this signal. They don't contain, or at least not specifically, the message of the Enlightenment, but rather contradictory discourses, seemingly meaningless phrases, i.e. literature insofar as it is not reduced to the communication of information, to knowledge, to progress5. And the world that burns these books is not a distant dictatorship ("in Chile, barely four years ago"), but, with its subways and expressways, its advertising and flat screens, it's the "gentle monster6" of our world, our civilization, rightly currently stricken by the disinheritance of literature. In his revolt and attempt to find his way back to books, Montag is accompanied by an old retired professor, Faber. Faber recalls the end of the old world, when he taught literature at the university:

Literature is not the only thing that's gone.

"It was the year I arrived in my class at the start of a new semester and found only one student to take O'Neill's Aeschylus drama course. Can you imagine? What a beautiful ice statue it was, melting in the sun. I remember the newspapers dying like giant butterflies. Nobody wanted to hear about them anymore. Nobody wanted them. On that, governments, seeing how advantageous it was to offer nothing in reading but passionate kisses and punches in the stomach, maintained this state of affairs with your fire-eaters7." (II, p. 91)

The teaching of literature is a "beautiful ice statue". No need for iconoclasts to destroy it. It's not the political power that takes the initiative for the end of literature; a disinherence has set in, a disinterest has become widespread8. The eradication of literature was already programmed before its institutional implementation, which Faber observes from the sidelines, with no desire to resist or fight: "Our civilization is turning to dust. Stand aside from the centrifugal force" (p. 909). We recognize here all the characteristic traits of what Antoine Compagnon designates as the antimodern attitude10.

First, the counter-revolutionary attitude: to the revolution instituted by "the governments" who have made a clean sweep of the past, Faber does not claim to oppose the resistance of an active struggle, the project of a counter-revolution. Rather, it's a matter of waiting for the inevitable collapse that this revolution has only precipitated11.

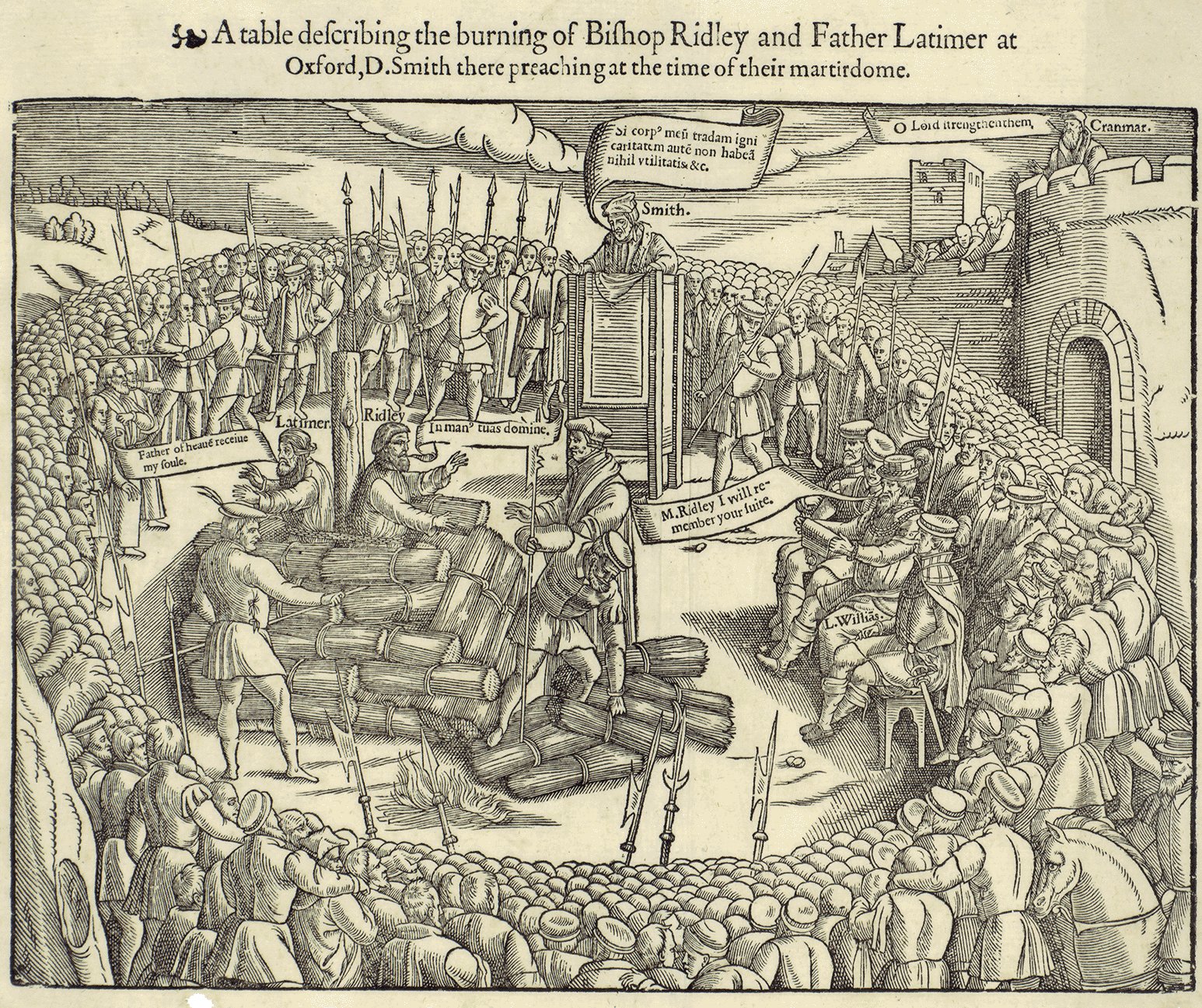

This political passivity is coupled with an attitude of rejection towards the Enlightenment and its ideology of progress. Faber hasn't installed a large wall-mounted TV screen in his living room, but a tiny12 set. He and his kind don't work. Last but not least, the books that are evoked as heritage in the process of being lost draw a curious canon. The first sentence that emerges as a shred of this lost knowledge is that of Hugh Latimer to his companion Nicholas Ridley, on the stake of Oxford's Protestant martyrs in 1555: "Be a man, Master Ridley! we shall on this day, by the grace of God, light a torch in England which I am sure will never be extinguished" (p. 48)13. This sentence, from Foxe's book of Martyrs14, is spoken by the old lady whose door the firemen have just broken down. A few pages earlier, Montag was rereading the firemen's charter in front of his comrades: "Founded in 1790, to burn English-influenced books in the colonies. First fireman: Benjamin Franklin." (p. 43)15. Bradbury parodies the American myth, the clean slate that is made of its English, Protestant, schismatic origins. While the caricature of Benjamin Franklin, the man of the Enlightenment, the drafter of the 1776 Declaration of Independence, the first U.S. ambassador to France, is sided with the dictatorship of the bookless world, it's Latimer and Ridley, moderate Protestants victimized by Marie la Catholique16, who become the tutelary figures of opposition to the bookless world. The old lady, repeating Latimer's phrase to Ridley as they both went up to the stake in Oxford in 155517, keeps his eyes lost in the vague18, addresses no one, takes no one to task, is not itself a person speaking, but a mere detached, desubjectivized language19. The sentence in the Foxe's book draws us into a position of withdrawal: the woman who utters it withdraws into this world of books that is about to burn; she ostensibly places herself on the side of erased memory; she is, as it were, already dead. Since this withdrawal, the pyre of martyrdom does not accuse; it haunts, it fascinates, it develops the image of a fire that is not that of the Enlightenment. It's the firemen now, founded by Benjamin Franklin, who embody a totalitarianism of the Enlightenment, while the flame of the partisans of the Book is identified with the fire of the stake, with that justice of the Inquisition praised by Joseph de Maistre20.

So it's fire against fire, the fire of the firemen against the pyre of the heretics, that Ray Bradbury builds the ideological opposition that structures his novel. But is it really an opposition? In the face of Faber's discourse on literature, or more precisely, his attitude of pessimistic withdrawal, the discourse of Beatty, Montag's captain, merely draws out the cynical and perverse framework of an identical relationship to the world.

"With educational establishments training more and more runners, jumpers, tinsmiths, tinkers, pilots, swimmers, and so on, instead of teachers, critics, scholars, artists, the word 'intellectual' has, of course, become the insult it deserved to be. We're always afraid of the unusual; surely you remember the kid in your class who was the strongest in theme, who always put himself in the spotlight to recite or answer while the others, sitting like leaden idols, hated him. Wasn't it that brilliant subject you chose to bully and torture him after study hours?" (p. 63-64)21

On the one hand, the athletes, who run, jump, swim, the workers who tin and tinker, virile and positive figures of socialist realism; on the other, the intellectuals, infatuated and torturous, destined to shine and suffer. This imaginary is no different from the one that haunts Faber; a single perverse sado-masochistic imaginary inhabits Montag's two antagonistic mentors. This perverse structure of antimodernity has been clearly identified by Antoine Compagnon22, who does not, however, draw all the consequences: the pervert denies otherness, crushes the Other or constitutes him as an other himself, only dreams or perpetrates the collapse of the Other to feed on it as his own abjection.

We can discuss the ideological configuration that Antoine Compagnon draws in the literary history of the nineteenth century, reorganized, between Joseph de Maistre and Maurras who serves as a repulsor and, in the process, a perverse legitimization, around hatred of equality, contempt for the republic, detestation of the Enlightenment. Indisputable, however, is the identification of part of today's academic community with this anti-modern position, which could be defined as detestation of Beatty's discourse, which is at the same time adherence to it. Antimodernity is above all anti-dialectical: it reduces the contradictory to the Same, hating the sadistic position of the Other in his discourse, without questioning the structure that assigns him the masochistic posture. She thus amalgamates Roland Barthes and Joseph de Maistre in the same fascination for their detestation (of the Revolution in Maistre, of the Avant-gardes in Barthes), which is first and foremost the modern literature professor's detestation of modern society, ideologically recuperated in a Maurassian-sweetened vision of the world, which literature would come to legitimize.

II. Temporality of literature: the hermeneutic mirage

How does literature come to legitimize this vision of a world in which it is destined to disappear? For it's not simply a question of a malaise in the teaching of literature, but of the very conception we have of literature, as if literature signified the malaise in civilization, occupied, within it, the point from which it was destined to collapse. In Fahrenheit 451, this sign of malaise, this point of collapse, is represented by Montag's irrational, incomprehensible movement towards books. The point is to understand what Montag goes looking for in books, what relationship he forms with them, what in literature unfolds that is absolutely irreducible and at the same time profoundly linked to the collapsing world in which he lives.

.What radically differentiates literature from the modern world is, first and foremost, its relationship to time: the depth and slowness of book time is contrasted with the speed and superficiality of world time. Montag doesn't access books directly: he comes to them through Clarisse McClellan's conversation.

"Have you ever watched the jet cars go by on the boulevards in this direction? [...] They always go so fast. If you show a passing driver a blurry, green patch, he has to say, 'Oh, yes, that's grass! A pink spot? Those are roses in a garden! White spots are houses. The brown ones, cows." One day, my uncle drove slowly along an autostrade. He was going seventy miles an hour. They put him in jail for two days. [...] Have you seen the hundred-meter-long signs in the countryside just outside town? Did you know that before, they were only ten meters long? But cars go by so fast now that they've had to lengthen them so that the advertising still retains its effect23." (p. 20)

Since the speed of the modern world, with its ever faster transport, its boulevards and freeways criss-crossing a territory they ignore, the other world is reduced to insignificant patches of color, gradually covered over, obscured by the growing surface of advertising billboards24. The other world, that of grass, roses, houses and cows, is no more real: it differs rather in the meaning it gives to things, in the slowness of their deciphering, their interpretation. Green, pink, white and brown cease to be stains and become signs to be read by those who experience slowness, itself a propaedeutic to the experience of reading. The world of speed is thus opposed by the world of reading, not as an artifice to reality, but as a scopic reality to a hermeneutic reality, as a system of stains to a system of signs25.

Entering literature, then, would be, even before reading, to experience this other, slow temporality, which interprets nature, which derives its value from this interpretation, that is, from this subjective appropriation of things through the meaning we give them. When Montag is about to burn the books in the old lady's attic, a book falls into his lap, a first line, inaugural for him, offers itself to his reading:

"In the rush, Montag had only a second to read one line, but it blazed in his mind for the next minute, as if branded with a red-hot iron: Time fell asleep under the afternoon sun. He dropped the book. Immediately another fell into his arms26."(p. 45)

The sentence that stands out is taken from an essay by Alexander Smith, entitled Dreamthorp, an imaginary burg whose quietude the narrator describes. In the next sentence, with his fingers arranged in a rectangle, the narrator detaches for his eye the frame, the snapshot of a photograph: I make a frame of my fingers, and look at my picture. But Bradbury retains only the first sentence, isolates the expression of time and removes the optical device in which Alexander Smith came to inscribe this representation of temporality.

It's a question of telling the story of time: telling the story of time would be the proper role of literature. Here we are at the heart of the hermeneutic conception of literature, as defined by Ricœur in the third volume of Temps et récit27. According to Ricoeur, there is an aporia of time, expressed first in the opposition between the Aristotelian conception of time as "something of movement" and the Augustinian conception of time as an apprehension of the soul. Aristotelian time is a time of the objective, physical world, a time of speed; Augustinian time is an inner, subjective experience, an intimate sensation of duration. Between these two relationships to time, no equivalence, no logical mediation is possible.

Ricœur extends and complicates this aporia by then contrasting Husserl's time with Kant's time: Husserlian phenomenology develops a conception of time as retention and protension, which introduces, into the succession of instants, the depth of memory, i.e. the intimate awareness of time. But Husserl, according to Ricoeur, "fails to represent the identity of the distant and the profound, which makes instants that have become other uniquely included in the thickness of the present instant" (p. 57): in other words, consciousness of the past and the past itself are at once the same moment and two completely different realities, a distant and a profound, a radically other instant and something caught up in the thickness of the present instant. Time thus continues to be splintered between a subjective and an objective apprehension, and the introduction of a depth of time does not reduce the aporia.

Finally, the Heideggerian conception of time as enveloped in Worry displaces the aporia without resolving it: "the have-been seems called by the to-come and, in a sense, contained within it"; we become aware of time whenever, more or less directly, we confront the idea of our own death. That's why this awareness emerges from our preoccupation with the to come, which then leads us to worry about what has been, as something in which our responsibility is engaged. It is only from this initial linking of the future with the past, of concern with responsibility (which are modalities of Souci), that we can access the most concealed dimension of time, the present, which preoccupies us as situation (p. 128). But if the Worry allows us to think the journey from the to the futureto the that has been, from there to the present as situation, and then to articulate these three dimensions of time, what is constituted in this journey draws either an individual destiny, or a collective destiny, and from there a history. Yet the passage from intra-temporality (my destiny) to historicity (the history of a people), from individual time to communal time, remains virtually unthinkable, with Heidegger suggesting at most a homology with dubious political implications (p. 138).

For Ricœur, only literature makes it possible to resolve the aporia of time, to operate this passage from an inside to an outside, from a psychology to a physics, from everyday life to history. This would be the function of literature: this is the process that Ricoeur designates as refiguration; to say that literature refigures temporal experience is to define literature as that passage that philosophy barred as an aporia of time: "the key to the problem of refiguration lies in the way in which history and fiction, taken together, offer to the aporias of time brought to light by phenomenology the replica of an poetics of narrative." (p. 181)

According to the model drawn by Ricœur, the world Ray Bradbury imagines, this world where firemen burn books, refigures the history of our civilization, that is, it transforms the data of our history, the historical configuration we are in, into figures of fiction. The aporia of time manifests itself between the speed of the world and the soul's demand for slowness: on the one hand, the autostrades, the lengthened posters, the world's patches of color; on the other, Time has fallen asleep under the afternoon sun. To this aporia, the narrative offers a rejoinder, the figure of books being burned. And this very figure is aporetic: either the books are burned because they have value, but the picture is meaningless of a civilization deserted by literature even before any political decision has been taken; or the books no longer have value, and the story of the books being burned has neither interest nor meaning. But it is precisely this logical contradiction in the figure of the books being burned that gives it its power of dreamlike, perverse fascination. This would seem to be a fundamental aporia of fiction, covering up, or supplanting, the aporia of time.

There is a profound, necessary, historical and ideological solidarity between the anti-modern, perverse superstructure of literary education and the hermeneutical infrastructure of a conception of literature founded on the aporia of time. This solidarity rests on a logical circle: once we consider all literature, all good literature, as fundamentally antimodern, we presuppose that literature necessarily proceeds to a detachment of fiction from modernity, that, faced with the to come of modernity, it retrojects its preoccupation with a that has been, according to the Heideggerian process of becoming aware of time. A contrario, if the fundamental function of literature were to be one of refiguration coming to cover the aporias of time, refiguration necessarily expresses the dehiscence between lived time and historical time, an anti-modern dehiscence to which the aporia of time always returns. Refiguration can only signify the divorce between the writer's creative consciousness and the world from which this consciousness feeds, the impossible passage from consciousness to the world, and, hence, the necessarily anti-modern character of the writer's posture.

.III. From time to space: towards a theory of devices

The rigor of the demonstration Ricoeur constructs does not prevent us from questioning its presuppositions: the first concerns the aporias of time, which constitute the prerequisite for the establishment of literature as refiguration. We understand the philosophical and critical approach, which consists in articulating, on the theme of time, the entire history of philosophy in a structure that Ricoeur designates as the "aporetics of temporality". But it's surprising that, in terms of physics, Ricoeur sticks to an Aristotelian conception of time, and regularly returns to the notion of "cosmic time28", which the theory of relativity, never mentioned, has definitively swept away. There is no longer, in physics, any absolute, cosmic time, and above all time is now a dimension of space, of a space which, according to the most recent developments in physics, would be endowed with much more than four dimensions.

.The irreducibility of time to space is forcefully upheld against the very philosophers Ricoeur reviews: for if Aristotle reduces time to movement (τι τῆς κινησέως, Physics, IV, 11, 219 a 10, p. 22), this is already a way of spatializing it; in Kant, Ricoeur notes that the representation of space, based on geometry, crushes that of time, which conditions the appearance of things, but itself remains invisible (p. 83). Doesn't the aporetic of temporality, beneath its logical and technical exterior, stem rather from an ideological refusal to assign time to space? For to think of time as a dimension of space reduces the literary fact to a question of representation, a question that does not specifically or exclusively engage literature. While the spatial paradigm dissolves literature as a separate field, narrative ceases to be the necessary form of literature, history ceases to be the necessary referent it refigures, refiguration ceases to be the necessary process of literary creation.

At the end of Bradbury's novel, Montag, who has killed his captain Beatty by turning his flame thrower against him, is pursued by the police, who unleash one of their electronic dogs against him to track him down. The hero has taken refuge at Faber's, and it's from his little TV set that he discovers that the dog is after him, and that the manhunt will be filmed:

."If he felt like it, he could linger here, and, comfortably, follow the hunt in all its phases, along the cul-de-sacs, through the streets, across the wide deserted avenues to the burning house of Mr. and Mrs. Black, and finally to this house where he and Faber sat drinking while the Robot, sniffing at the end of the trail, silent as the wing of death, would come to rest behind this window. Then, if he wished, Montag could get up, walk over to the window, without losing sight of the TV screen, open the window, lean out, turn around and see himself emerging like a theatrical hero, on the small luminous screen, a drama to be contemplated with an objective eye, knowing that in other living rooms, he appeared life-size, in color, his exact replica in three dimensions! And if he had a keen enough eye, he could still see himself, for a moment before falling into oblivion, pierced for the benefit of the countless spectators who, roused from sleep a few minutes earlier by the sirens wailing from the walls of their living rooms, had settled down to watch the wild hunt, the 'organized battue against a hunted man, a lonely man29. " (p. 133)

The manhunt organizes the integration of the two worlds through television. This integration is indeed that of two temporalities: on the one hand, the comfortable idleness of the television show, inside the home, lazily unrolls the glitter of its sleepy nocturnal slowness; on the other, breathless, unbridled, the race outside, from the machine to the fugitive, from the fugitive to death, precipitates a terrifying countdown. Speed and slowness no longer correspond respectively to modernity and anti-modernity; the technique of the robot dog is opposed by the technique of television, Montag pursued, Montag a viewer; the other world is reduced to the same, the sadistic game is enveloped in its masochistic contemplation, according to a perverse device.

.But above all, the time of the manhunt, that of the streets and that of the screen, the real and the represented, comes to be inscribed in a device that settles its aporia.

A device, not a narrative: here, there is neither succession nor event, but precisely the opposite: a falsification of the event, with the camera finally filming, from afar, a fictitious killing while Montag is, on the other side of the river, out of reach. The device encloses time in a space whose trajectory it organizes up to a tilting surface that ensures the junction of the real and the represented. This surface is the window from which the robot dog is supposed to leap, towards which Montag could step forward in the face of his death. The device is tended towards this encounter, which is at the same time a dead point, the locus of the aporia of time: "And if he had a sharp enough glance, he could still see himself, for a moment before falling into oblivion"; the glance, the optical device, not the narrative, are the means of representing the impossibility, at this point, of a temporal join, and the identification of this impossibility with the face-to-face with death.

Or this time whose conjunction is not made is neither the external time of history, with its succession of events, nor the internal time of subjectivity, with its depths and retentions. "Then, if he wished... it's a time of hypothesis, unfolding in a countdown, that is, in a system of reversed accounting. Fragmented, splintered time of the televisual spectacle, virtual time of subjective conjecture, time is a lure framed by the device, just as Dreamthorp's sentence about time, spouted to Montag's eyes in the old lady's house, was in fact immediately framed by the narrator's fingers fixing it as a tableau: I make a frame of my fingers, and look at my picture...

What does the device do? It inscribes the antimodern into modernity, not as its masochistic victim, but as the possibility and surprise of a thwarting. In the device, there's a game of the game, a way out. A system of control, a hegemonic automatism that normalizes the world, the device is also a way out, a means of playing with structure. Literature is the exercise of this game: the freedom of the game is conditioned by the symbolic community or communities that the device establishes, the viewing public on the one hand ("Would he have time to make a speech?"), the community of the marginalized on the other.

What's the point of this game? Perhaps it doesn't, but rather introduces a new relationship, always already there, of which jouissance is the foundation. And isn't it the Platonic teaching that all teaching proceeds from jouissance, that from it it arranges its winged carriage? Not for withdrawal, but for elevation.

Notes

See, from this apparently generous, actually ultra-conservative perspective, the debate launched by Martha C. Nussbaum's book, Not for Profit. Why Democracy Needs Humanities, Princeton University Press, 2010.

" Fahrenheit 451 - the temperature at which book paper catches fire, and burns..." (Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451, A Del Rey Book, NewYork, The Random House Publishing Group, 1953, 1991)

Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451, French trans. Henri Robillot, nrf, Gallimard/Denoël, 1955, collection 1000 soleils, 1977. References to the French translation are given in this edition.

Beatty explains to Montag: "The fact is, we hardly had a role to play before the advent of photography. Then came cinema... at the beginning of the XXe century. Then radio. Then television. The masses element then entered the scene." (p. 60; "The fact is we didn't get along well until photography came into its own. Then - motion pictures in the early twentieth century. Radio. Television. Things began to have mass.", p. 54.)

" books tell nothing. Nothing you can believe or teach others. If they're novels, they're about beings that don't exist, products of the imagination. If they're not, it's even worse. Each teacher calls the other an idiot. [...] You come out of it completely lost." (p. 67; "the books say nothing! Nothing you can teach or believe. they're about nonexistent people, figments of imagination, if they're fiction. And if they're nonfiction, it's worse, one professor calling another an idiot [...]. You come away lost.", p. 62)

Raffaele Simone, Le Monstre doux : l'occident vire-t-il à droite?, trans. française Katia Bienvenu, Gallimard, Le Débat, 2010. Raffaele Simone takes his inspiration for this expression from a text by Tocqueville: "I want to imagine under what new features despotism might occur in the world: I see an innumerable crowd of similar and equal men who turn restlessly on themselves to procure small and vulgar pleasures, with which they fill their souls. [...] Above them rises an immense and tutelary power, which alone assures their enjoyment and watches over their fate. It is absolute, detailed, regular, far-sighted and gentle. [...] It willingly works for their happiness; but it wants to be the sole agent and arbiter of it; it provides for their security, foresees and assures their needs, facilitates their pleasures [...]; what can it not do to remove from them entirely the trouble of thinking and the trouble of living?" (Alexis de Tocqueville, De la démocratie en Amérique, 1840, Gallimard, 1968, p. 347-348)

" That was the year I came to class at the start of the new semester and found only one student to sign up for Drama from Aeschylus to O'Neill. You see ? How like a beautiful statue of ice it was, melting in the sun. I remember the newspapers dying like huge moths. No one swanted them back. No one missed them. And then the Government, seeing how advantageous it was to have people reading only about passionate lips and the fist in the stomach, circled the situation with your fire-eaters." (p. 89)

Compare with Beatty's speech: "There you go, Montag, the government had nothing to do with it. No decree, no declaration, no censorship at the starting point. No! Technology, exploitation of the mass factor, pressure on minorities, and, thank God, the whole thing was played out." (p. 63; "There you have it, Montag. It didn't come from the Government down. There was no dictum, no declaration, no censorship, to start with, no! Technology, mass exploitation, and minority pressure carried the trick, thank God.", p. 58)

" Our civilization is flinging itself to pieces. Stand back from the centrifuge." (p. 87)

Antoine Compagnon, Les Antimodernes, de J. de Maistre à R. Barthes, Gallimard, nrf, 2005.

"Let's think it over, we'll see that the revolutionary movement once established, France and the Monarchy could only be saved by Jacobinism", wrote Joseph de Maistre (Considérations sur la France, in Écrits sur la Révolution, ed. Jean-Louis Darcel, PUF, 1989, p. 106; see A. Compagnon, op. cit., p. 29).

"I've always wanted a small post, one I could approach without risking being deafened by bellowing, a surface I could mask with my hand if necessary." (p. 132; "He took Montag quickly into the bedroom and lifted a picture frame aside revealing a television screen the size of a postal card. "I always wanted something very small, something I could walk to, something I could blot out with the palm of my hand, if necessary, nothing that could shout me down, nothing monstrous big."", p. 132-133)

" Play the man, Master Ridley; we shall this day light such a candle, by God's grace, in England, as I trust shall never be put out" (p. 36). The exact text is: "Be of good comfort, Master Ridley, and play the man! We shall this day, etc"

John Foxe, Acts and Monuments of these latter and perillous days, touching matters of the Church [...], popularly known as the Foxe's Book of Martyrs, ed. John Day, London, 1563, enlarged English edition (1800 pages in-folio) compared to the original Latin edition of 1559. The Foxe's Book of Martyrs is considered the most important publishing venture of the period, and marks the beginning of printed English literature. The famous phrase did not appear in the first edition of Foxe's Book.

" Established, 1790, to burn English-influenced books in the Colonies. First Fireman: Benjamin Franklin." (p. 34)

Ridley, Bishop of London, had made a name for himself in the vestments controversy sparked by John Hooper in 1550: Hooper refused his ordination in priestly vestments, and refused to declare his faith in all the saints. Ridley, himself committed to the Reformation, did not accept this independence from the institution of the Church. The King and his Council declared the matter "indifferent". The controversy escalated, however, Ridley turned the Council in his favor, Hooper was arrested in 1551 and submitted: he was ordained Bishop of Gloucester and preached before the King in priestly vestments.

But it was the Catholics who led Ridley to the stake. When Edward VI died, Ridley defended the deceased king's will and Lady Jane Grey's estate. When Mary the Catholic was proclaimed queen, he was arrested along with Jane Grey's supporters, and the heresy trial served as a pretext for their elimination.

" as they were being burnt alive at Oxford, for heresy, on October 16, 1555 ", p. 40.

" her eyes seemed to be trying to remember something ", p. 36.

" her tongue was moving in her mouth [...] her tongue moved again ", p. 36.

"there is nothing so just, so learned, so incorruptible as the great Spanish courts [...], there can be nothing in the universe more calm, more circumspect, more human by nature than the tribunal of the Inquisition." (Joseph de Maistre, Lettres à un gentilhomme russe sur l'Inquisition espagnole, in Textes choisis présentés par E. M. Cioran, Monaco, éd. du Rocher, 1957, p. 166; quoted by Antoine Compagnon, op. cit., p. 142-143, and at greater length by Roland Barthes as an epigraph to his course on Le Neutre, 1977-1978, Seuil/IMEC, 2002, p. 28)

" With school turning out more runners, jumpers, racers, tinkerers, grabbers, snatchers, fliers, and swimmers instead of examiners, critics, knowers, and imaginative creators, the word "intellectual", of course, became the swear word it deserved to be. You always dread the unfamiliar. Surely you remember the boy in your own school class who was exceptionally "bright", did most of the reciting and answering while the others sat like so many leaden idols, hating him. And wasn't it this bright boy you selected for beating and tortures after hours? " (p. 58)

A. Compagnon, op. cit., p. 146 ("de Maistre qui aime les effets pervers") and especially p. 418 ("l'antimoderne est toujours pervers").

" Have you ever watched the jetcars racing on the boulevards down that way? [...] "I sometimes think drivers don't know what grass is, or flowers, because they never see them slowly," she said. "If you showed a driver a green blur, Oh yes ! he'd say, that's grass ! A pink blur ! That's a rose garden! White blurs are houses. Brown blurs are cows. My uncle drove slowly on a highway once. He drove forty miles an hour and they jailed him for two days. [...] Have you seen the two hundred-foot-long bill-boards in the country beyond town? Did you know that once bill boards were ony twenty feet long? But cars started rushing by so quickly they had to stretch the advertising out so it would last." (p. 9)

Compare with the billboards put up in Russian villages by Potemkin as Catherine II passed.

In the same vein, Clarisse praises history painting against abstract painting: "And in museums, have you been there by chance? Nothing but abstract, period. My uncle says it used to be quite different. A long time ago, paintings sometimes expressed things or even represented people." (p. 39; "And at the museums, have you ever been? All abstract. That's all there is now. My uncle says it was different once. A long time back sometimes pictures said things or even showed people.", p. 31)

" In all the rush and fervor, Montag had only an instant to read a line, but it blazed in his mind for the next minute as if stamped there with fiery steel. "Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine." He dropped the book. Immediateley, another fell into his arms. " (p. 37)

Paul Ricœur, Temps et récit, 3. Le temps raconté, Seuil, 1985, Points, 1991. References are given in the "Points" collection edition.

Ricœur speaks successively of "cosmological conception of time" (p. 21), "cosmological thesis" (p. 22), "cosmological theory of time" (p. 25), "cosmological instant" (p. 36), "time of physics", or "physical time" (p. 43), "objective time" (p. 44, 73, 75), "objective course of world time" (p. 45 quoting Husserl)...

" If he wished, he could linger here in comfort, and follow the entire hunt on through its swift phases, down alleys, across streets, over empty running avenues, crossing lots and playgrounds, with pauses here or there for the necessary commercials, up other alleys to the burning house of Mr. Black. and Mrs. Black, and so on finally to this house with Faber and himself seated, drinking, while the Electric Hound snuffed down the last trail, silent as a drift of death itself, skidding to a halt outside that window there. Then, if he wished, Montag might rise, walk to the window, keep one eye on the TV screen, open the window, lean out, look back, and see himself dramatized, described, made over, standing here, limned in the bright small television screen from outside, a drama to be watched objectively, knowing that in other parlors he was large as life, in full color, dimensionally perfect! and if he kept his eyes peeled quickly he would see himself, an instant before oblivion, being punctured for the benefit of how many civilian parlor-sitters who had been wakened from sleep a few minutes ago by the frantic sirening of their living room walls to come watch the big game, the hunt, the one-man carnival. " (p. 134-135)

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Critique de l’antimodernité : l’espace contre le temps de la littérature, Fahrenheit 451 », Enseigner la littérature aujourd’hui, resp. Claude Pérez, Fabula, novembre 2011

Critique et théorie

Archive mise à jour depuis 2008

Critique et théorie

Généalogie médiévale des dispositifs

Entre économie et mimésis, l’allégorie du tabernacle

Trois gouttes de sang sur la neige

Iconologie de la fable mystique

La polémique comme monde

Construire Sénèque

Sémiologie classique

De la vie à l’instant

D'un long silence… Cicéron dans la querelle française des inversions (1667-1751)

La scène et le spectre

Dispositifs contemporains

Résistances de l’écran : Derrida avec Mallarmé

La Guerre des mondes, la rencontre impossible

Dispositifs de récit dans Angélique de Robbe-Grillet

Disposition des lieux, déconstruction des visibilités

Physique de la fiction

Critique de l’antimodernité

Mad men, Les Noces de Figaro

Le champ littéraire face à la globalisation de la fiction

Théorie des dispositifs

Image et subversion. Introduction

Image et subversion. Chapitre 4. Les choses et les objets

Image et subversion. Chapitre 5. Narration, récit, fiction. Incarnat blanc et noir

Biopolitique et déconstruction

Biographie, biologie, biopolitique

Flan de la théorie, théorie du flan

Surveiller et punir

Image et événement