There's a consubstantial unrepresentability to the mystical fable, founded on the experience of night, confrontation with the invisible, the eccentric experience of the collapse of the codes and institutions of the sign. The fable itself, defined in the classical language as " tale, fabulous narrative ", " invented to help the foiblesse des enfans ", " is also taken in a collective sense, to signify all the Fables of Payenne antiquity [...] ; it is the Theology of the Pagans1. " We are apparently at the antipodes of religious painting, governed by the strict specifications of institutional commissions, anchored to the biblical text, codified in a learned typology, mobilized for public edification.

Idiot, singular, erratic, the mystical fable seems to be defined precisely by its fundamental resistance to the apparatuses of representation and the visual devices that bear them. This, at least, is what Michel de Certaux suggests, when he evokes Marguerite Duras before the idiot of Histoire lausiaque :

" The beggar woman remains invisible in India Song. Nameless and faceless. Her shadow alone crosses the image [...]. She does not speak. She makes speak2. "

And in the same way, when Piteroum appears, the renowned anchorite before whom everything bows, the fifth-century madwoman-in-Christ, suffers the pain of the convent's back kitchens, doesn't show herself, refuses to appear, manifests herself as a mystic by her lack of presence, her resistance to representation :

" In contrast to the imagery that idealizes the Virgin Mother, unified by the Name of the Other, with no relation to the reality of the body, the idiot is all in the unsymbolizable thing that resists meaning3. "

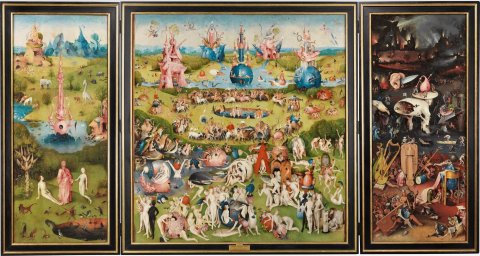

Garden of Delights triptych - Hieronymus Bosch

The purpose of this paper is to show that, on the contrary, because it is first and foremost against the institution of the Word that the mystical fable unfolds and organizes itself, the image, the theological icon, plays an essential role in it and, in an apparently anarchic field that resists any structural closure, provides the counter-system of the mystical fable with the device for its expression, its dissemination, its organization. Michel de Certaux himself invites us, despite this introduction, to follow this path, defining the fable as a place, its discourse as a topic of misguidance, its medium as a tableau qui regarde whose model would be Jerome Bosch's Jardin des Délices and theoretical support the mysticism of the gaze in Nicolas de Cues.

The aim here is not to explore the psychotic margins of painting, but rather, from the very heart of the religious institution of the image, what necessarily articulates, at the moment of transition from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, canonical imagery to its mystical deconstruction as fable.

Organizing invisibility : the closed polyptych

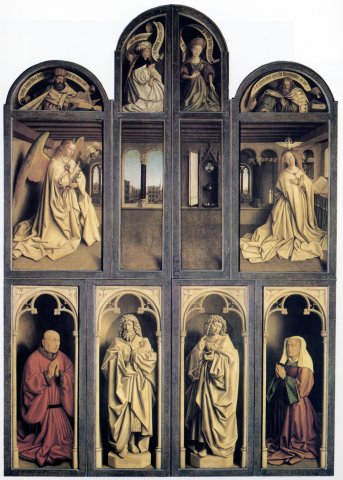

Annunciation (Mystic Lamb polyptych in Ghent, shutters closed) - Van Eyck

With its shutters closed, the polyptych of the Mystic Lamb by the van Eyck brothers gives no hint of its contents. In the lower register, four figures stand in their own compartment, like an iconostasis: on the outside - the donors, in the center, imitating statues - the two Saints John, the Baptist on the left, the Evangelist on the right, former patrons of Ghent Cathedral before it was dedicated to Saint Bavo. Slightly turned towards the center of the altarpiece, the pious patrons, Jodocus Vijd and Lysbette Borluut, pray before the statues of the saints. This lower register is that of the real thing, of the very church where the altarpiece stands.

Above, the Annunciation introduces us, from the real, to religious history, with a central scene for the institution of Christianity : the archangel Gabriel bearer of the divine message stands on the left, a branch of lily in hand, uttering in golden letters the evangelical greeting : " Ave Maria | [gratia] plena dominus tecum " ; symmetrically to him, on the right-hand panel, the Virgin, hands crossed on her chest, turning away from the book she was reading set against the window, answers him, on the same horizontal line, with inverted characters running from right to left : " Ecce ancilla d[omi]ni ". She doesn't look at the angel, but with her eyes raised to heaven, she receives the Holy Spirit, whose dove stands on her head.

Finally, in the upper register of the closed altarpiece, the prophets Zechariah and Micah and in the center the sibyls of Cumae and Erythra announce the coming of Christ.

These three registers organize the real invisibility of Christ : the donors see only statues of saints the pagan world prefigures in aenigmate and the Annunciation announces in the mere suspense of the gold letters what will only be revealed once the panel is opened. The compartmentalization of the image by the interplay of the polyptych's panels underlines the fragmentary, veiled status of what precedes the mystical vision, and identifies the wooden panel with the wall that must be crossed to gain access.

The van Eyck brothers painted the altarpiece in the 1420s, and it was placed on May 6, 1432 on the altar of the commissioner's chapel, in the church then called St. John.

The wall, the veil, the cloud : topology of the image according to Nicolas de Cues

In 1453, on the border between Italy and Austria, Nicolas de Cues wrote the De icona, de visione Dei, improperly translated by Agnès Minazzoli as Le Tableau4, more aptly by Michel de Certaux as L'Image5. Victor Stoichita has in fact shown how the very notion of the painting was only very gradually established during the 16th century in our culture, which was then still a culture of the icon, where what stands before us is not an object we look at, move or manipulate, but an image that imposes itself on us as the image of God6.

Nicolas de Cues develops his theory of docte ignorance, which he applies to the relationship established with us by the presence before us of an image, an icon, a representation of the face of God :

" O too beautiful face of which, to admire its beauty, is not enough all that it gives to see of itself ! In all faces we see the face of faces veiled and enigmatic. And we don't see it in unveiling until, above all faces, we enter a kind of deep secrecy and silence, which has nothing to do with science and the concept of face. For there is a cloud, a fog, a darkness, or ignorance, where he who seeks your face enters, when he leaps over all science and concept, a cloud below which your face can only meet veiled. It is the cloud itself that reveals that there is there one face above all the veils7. "

The image does not immediately manifest itself to us : what it gives us to see of itself is not enough, its beauty exceeds the immediate visible. The closed altarpiece indicates this inadequacy. It shows us a series of figures, faces, but the only Face that really counts, that of God, is first veiled, before being revealed to us. It is only in a second stage, after the cloud has passed, in the cloud itself, that it is revealed : revelate videtur, we see it revealed, without veil and in the movement of revelation, we see it in unveiling.

This cloud, caligo, tenebra, ignorantia, refers to the cloud of Sinai that Moses crosses to receive the Tables of the Law :

" Then Moses went up on the mountain. The cloud covered the mountain. The glory of Yahweh settled on Mount Sinai, and the cloud covered it for six days. On the seventh day, Yahweh called Moses from the midst of the cloud. To the Israelites, Yahweh's glory looked like a consuming flame on the mountaintop. Moses entered the cloud and went up the mountain. And Moses remained on the mountain forty days and forty nights8. " (Exodus, XXIV, 15-18)

What was then given only to Moses to cross and approach, is accessible to the Christian through the intermediary of the icon. But this crossing involves a contradiction for it requires leaping over all science and concept (omnem scientiam et conceptum transilire), for the apprehension of God is sensitive, immediate it short-circuits the explanations, the developments of discursive knowledge. We access God directly, we understand him without knowing the content of knowledge to which this understanding should correspond : this is docte ignorance, founded on the coincidence of opposites9 in the vision of God God reveals himself as both visible necessity and intellectual impossibility, he makes God as necessity and God as impossibility coincide in this revelation.

The novelty of De icona consists in identifying this contradiction with a place, the very place of the image, understood as an enclosure that must be broken in order to penetrate :

" And you breathed life into me, Lord, you who are the food of great souls, so that I would do violence to myself, for impossibility coincides here with necessity. And I've spotted the place where you are in the unveiling, a place surrounded by the coincidence of contradictories. And this place is the wall of paradise, where you live, whose door is guarded by the sublime spirit of reason: if it is not defeated, the entrance will not appear. Beyond the coincidence of contradictories, then, you can be seen, but never below it. If then impossibility is a necessity in your gaze, Lord, there is nothing your gaze cannot see10. "

The image is a murus paradisi, it is the enclosure of the walled garden of Eden, of the hortus conclusus, not the garden itself, but the wall of the garden : Et iste est murus paradisi. What counts is this crossing, the transgressive violence of this access : I do violence to myself, I cross the belt where the contradictions of learned ignorance coincide, I cross the wall of paradise, I pass through the door guarded by reason, I make manifest, by force, the passage, ingressus. It's all played out in the shift from the hereafter to the hereafter, from the citra to the ultra. And it's played out in the form of a battle against reason, which pits the logical contradictions of God's vision against the mind. This mystical forcing, clearly referred to the figure of Moses penetrating the cloud on Sinai, is part of a long theological tradition that identifies the image with the biblical Tabernacle, with its veil separating the Holy, visible, from the Holy of Holies, a priori hidden from view. In the Heavenly Hierarchy, Denys was already resorting to the metaphor of the veil and the paradox of an illumination that passes through concealment :

" It is indeed impossible for the ray of divine light to illuminate us in any other way than after having, under the variegation of sacred hangings, concealed itself for our elevation, and, having taken on, by the effect of a paternal Providence, a garment consistent with our familiar surroundings11. "

The variegation of the sacred hangings, ποικιλία τῶν ἱερῶν παραπετασμάτων, refers exactly to the decoration of the stretched fabrics of the tabernacle tent, while the concealment of the divine ray, περικεκαλυμμένην, is identified with cross-dressing through clothing, διεσκευασμένην. Nicolas de Cues therefore in no way invents the device, which is formulated from the very beginnings of mystical literature. But what Denys describes as an accommodation, as an economy of image12, becomes in the 15th century an experience of the limit and its transgression, a focus on this moment of crossing that is no longer simply identified with a revelation, but also with a struggle against reason, a logical forcing, a break with the discursive.

The opening as nuptial threshold : from image to device

Polyptych of the Mystic Lamb - Hubert and Jean van Eyck

The polyptych of the Mystic Lamb materializes this device in a very concrete way, by opening the panels. The center of the closed altarpiece exposes, in the gallery where the archangel and the Virgin stand, between them, two openings, one on the left overlooking an urban exterior, perhaps the very square of Ghent that we would see from the cathedral, the other constituting a simple niche equipped with a washbasin, with a towel hanging perpendicular to the wall. Above the washbasin, a small, three-lobed opening lets in a dim light : we understand from the arrangement to the right behind the Virgin of a second room that this opening does not open onto the outside.

.

The Coronation of the Virgin - Enguerrand Quarton

In other words, between the bearer of the divine message and the one who receives it, at the junction through which the altarpiece will open towards the contemplation of the mystic lamb, the van Eyck brothers arrange the beat of the open and the closed (the sky and the napkin veil), the pure and the impure (the city and the hand-washer), the profane and the sacred (antique column versus Gothic lacework of what could be a small sacristy tabernacle). The eye thus comes to rest on this threshold and cleft, in the in-between of the passage, from gallery to chamber place, where the Annunciation stands.

The Coronation of the Virgin (Uffizi version) - Fra Angelico

Once the altarpiece is opened, the slit reveals Christ in Majesty blessing at the top, flanked by the Virgin and John the Baptist. It is indeed Christ he wears the red mantle of the Incarnation and, placed next to the Virgin, offering a crown at her feet, he is part of the then flourishing topicality of the Coronations of the Virgin : those by Fra Angelico in Florence, for example the one in the Uffizi dated 1434, those by Sano di Pietro in Siena, for example the one in the Pinacothèque Nationale painted in 1440, the one by Enguerrand Quarton in Villeneuve-lès-Avignon in 1454, with the same red cloaks as the one in Ghent13.... The series has its origins in the gold-ground mosaic executed in 1140 in the apse of the Basilica of Santa Maria del Trastevere14, where Christ welcomes at his side his mystical Bride, identified by the text she unrolls before her with the Bride of the Song of Songs : Læva ejus sub capite meo, et dextera illius amplexabitur me, His left hand under my head, and his right will embrace me (Ct, 2, 6). But the Book of Christ bears Veni electa mea et ponam in te thronum meum, Come my chosen one, and I will place my throne in you, a formula found in Bartholomew of Trent and James of Voragina, and used in liturgical chants15 : she then points to the Virgin. Above Christ, the hand of the paternal God holds a wreath of foliage destined to crown the Virgin-Bride-Church. Beneath the mystic couple, a line of sheep represents the Church's flock, with the mystic lamb haloed in red at its center. The combination of the Virgin's coronation and the allegory of the mystic lamb prefigures the layout of the Ghent polyptych. In Trastevere, Christ is not yet facing the Virgin, as would become commonplace in the Coronations of the Virgin of the 15th century. Imperial, he faces the viewer, like that of the Van Eyck brothers : the arrangement of the figures is enough to signify this enthronement, with which John the Baptist is associated as the figure of the mystic lamb.

The Coronation of the Virgin - Sano di Pietro

In fact, the mystical lamb is extrapolated from an exclamation found at the beginning of John's Gospel : "... he saw Jesus coming to him, and he said Behold the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world " (ecce agnus Dei qui tollit peccata mundi, Jn 1,29). John the Baptist preaching to his disciples in the desert signifies to them through this vision of Jesus that he is not himself the Messiah, merely announcing him in ænigmate through his preaching.

The Coronation of the Virgin (Santa Maria del Trastevere)

In the Ghent altarpiece, the presence of John next to Christ and the Virgin again emphasizes the threshold that the image invites us to cross, and the violence against reason that this crossing implies : John remains in the discourse, his open book on his lap places him on the side of the text, below the contradictorium coincidentia16. But with his index finger he indicates the vision of God, i.e. the leap to be made, from one compartment of the polyptych to the next, from his preaching to the mystical face-to-face. Here, the Van Eyck brothers mobilize another topic, that of the Ecce agnus dei. Following in their footsteps is one by Giovanni di Paolo, executed around 1455-1460, in which John and his disciples stand on a square of desert, while Jesus appears on another square, opposite them. Between these zones, these territories, runs a darker band, a depression in the ground even more neutral than the desert, a breakdown in the very texture of the representation. Jean indicates the leap to be made by the eye from one zone to the next, a leap exacerbated by the compartments of the polyptych and insisted upon by Nicolas de Cues. In Dirk Bouts' work, Christ stands squarely on an island in the Jordan, so that the vision foreshadows his baptism by John.

Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (Ghent Altarpiece) - Jean van Eyck

In the Ghent polyptych, the vision is of a literal agnus around which the faithful who have come to adore him are spread out in a star-like pattern. All commentators17 emphasize the medieval encyclopedic architecture of this starburst : the van Eyck brothers did not depict a motley crowd of spectators, but arranged homogeneous groups, like syntagms whose sequence makes sense as a totality of the world. Starting from the left and turning counter-clockwise, we first recognize the Jewish prophets with their turbans and two-pointed beards imitating the shape of the tablets of the Law. Kneeling before them, the pagan writers hold their books. On the right, still in the foreground, we pass to the twelve apostles in their robes, behind whom stand the Fathers of the Church and the saints, St. Stephen, the first martyr, carrying in front of him, in his chasuble, the stones with which he was stoned, and behind him, further to the right, St. Liévain, evangelizer of Flanders and patron saint of Ghent, holding in a claw his torn-out tongue. In the background on the right, displaying their palms, the women martyrs, and facing them on the left, the men, first the ecclesiastics, and behind them the monks, recognizable by their tonsure finally, the simple laymen emerge from the bush of martyrdom roses.

It's immediately striking that they're not looking at the mystic lamb. They are not spectators around a stage : they are there not to see, but by state, that is, to be seen. God sees them : the mystic lamb first, and the crowning Christ above him, both painted from the front, darting from the frozen center of their impassive pupils the gaze of the One who sees all, omnia videntis, omnivoyeur.

The mystical fable, between icon and stage

If we return to Nicolas de Cues' De icona, we now understand that its subtitle, de visione dei, indicates not so much the vision we may have of God as the vision God exercises over us. This is what the preface to De icona insists on. In it, Nicolas de Cues addresses the monks of Tegernsee, to whom he sends, along with his work, a painting depicting the Holy Face, icona Dei :

" I have found nothing more suitable for my purpose than the image of an omnivoyant whose face is painted with such subtle artistry that it seems to look at everything around it. [...] Stand at an equal distance from her and look at her: from any angle, each of you will experience that you are the only one to be seen by her. [...] Knowing that the image is always fixed and motionless, he will be astonished by the movement of this motionless gaze. If he fixes his eyes on it and makes the journey from west to east, he will discover that the image continually attaches its view to him, and that it doesn't leave him either if he makes the reverse journey18. "

The monks are invited to take part in an exercise: they will turn around the painting, and they will notice that the eyes of the portrait, although perfectly fixed, will give them the illusion of turning at the same time as them, of following them with their gaze.

Through this exercise, a struggle seems to be waged between the affirmation of a subjectivity, of a gazing singularity, and the fascinating power of the face to which the image seems to be summed up : face of the One who, whoever I am, wherever I am, is looking at me. The vision of God is concomitantly subjective (I look at Him as I turn around) and objective (omnia videntis visio, it looks at me), it receives illumination and it produces, at its periphery which it traverses, the image as gaze seen. This circular radiance of visionary fascination, which emanates and directs its rays from a center, is found in the Ghent Mystic Lamb, where it is manifested by the epiphany of the Holy Spirit at the top center of the panel, projecting its golden rays Pentecost-style onto the figures arranged in a star around the lamb. Under the celestial mandorla, the projection is redoubled by the spray of the Lamb's blood into the Eucharistic cup on the altar, and repeated below by the gushing of the fountain. When the worshipper enters the church, the font and baptismal font welcome him with their water, the altar faces him, and the light from the stained glass overhangs him: the space described here is that of the church, and the event is the Eucharist. The panel represents both, statically, the Church community, starred into compartments constituting its orders, its categories, and, dynamically, the faithful's path through the church, from its entrance below to the communion it offers in the center and the revelation it promises above. A path thus emerges at the midpoint of the image, at the cut of the polyptych, where it opens and closes. In front of the altar, the two angels waving their censer identify the place of the altar with the Holy of Holies, whose entrance is protected by the two cherubim of the mercy seat. Behind them, the cross and the column of flagellation, instruments of the Passion, designate this center as a trial, a violence of passage.

The De icona of Nicolas de Cues is tense between these two conceptions of the image : the old one identifies the image with an objective vision of the Church community ; the new one, which would triumph with the invention of scenic perspective (Alberti's De pictura dates from 1436), brings the image into being at the end of a journey in the church towards vision, after having confronted it with the test of the screen, with this crossing of the belt where, in Nicolas de Cues' expression, contradictories coincide. What Nicolas de Cues imagines here identifies the image with a mystical fable, with the narration and unfolding of a journey, whose horizon is the advent of a device of representation, the setting in space of a system of gazes: the revelation of the divine gaze and the journey of the mystical gaze meet. Michel de Certeau highlights, in this conjunction of gazes, the geometrical topology of a space that is both of vision and intellection :

.

" The gaze of the painting constitutes a point. [...] A space is thus generated thanks to the equal lines drawn from the point19. Equidistant from the painting, the monks represent this property. They make the semicircle. They construct a mathematical figure in view of operations of the mind20. "

In this mystical space of the image, we recognize both the experience imagined by Nicolas de Cues, walking in a circle around the image of God, whose gaze, though fixed on the drawing or painting, seems to follow us, and the revelation of the mystical lamb in the Ghent altarpiece, arranging its figures from the fixed point of the frontal gaze, that of Christ in majesty and that of the lamb. It's not yet the optical space of the scene, but it's already a space that unfolds as representation and organizes itself as an enclosure to be crossed, as a pathway from the vague, nebulous beyond to revelation, to light, in a space beyond, restricted, circumscribed, unreal. The actual border of the image thus enters into the intrinsic layout of the icon : the space of the icon is no longer the image alone sent by Nicolas de Cues to his correspondents at Tegernsee Abbey it includes, as the geometrical foundation of the symbolic belt where opposites coincide, the circular path by which the preface to the De icona accompanies this dispatch. In this device, the monks are not yet the characters of a painting, but already the topological property of this painting, i.e. this game of " generating a space thanks to equal lines drawn from a point " from which the classical stage will emerge, with its single focal point, its ramp and backstage boundaries (heirs to the cloud, the mystical wall that must be crossed), and its mute but profound connection with the parterre, which looks at it only on condition that the representation denies it.

Thus, the mystical fable plays, in the genesis of the modern image, its role of conjointure and supplement : eccentric experience, mystical derailment of the vision of God that it subjectifies, that it hypostasizes at the obscure moment of passage rather than at its luminous fulfillment, it ensures by the device it deploys the passage from the theological icon to the scene of the painting.

Key words : Van Eyck - Nicolas de Cues - image - coincidence of contradictions - vision - mystical lamb - crowning of the Virgin - scenic device

Notes

Dictionnaire de Trévoux, Nancy, 1738-1742, p. 620-621.

Michel de Certaux, La Fable mystique, I. XVIe-XVIIe siècle, Gallimard, 1982, Tel, 1987, p. 48.

Michel de Certaux, op. cit., p. 51.

Nicolas de Cues, Le Tableau ou la vision de Dieu, trans. Agnès Minazzoli, Cerf, " La nuit surveillée ", 1986 [2007, 2009].

Michel de Certaux, La Fable mystique. XVIe-XVIIe siècle. II, ed. L. Girard, Gallimard, Nrf, 2013, " Le regard : Nicolas de Cues ", p. 51sq. Michel de Certaux emphasizes the contemporaneity of Van der Weyden (cited by name in the preface to De icona), Van Eyck and the Master of Flemalle with Nicolas de Cues (op. cit., p. 65).

Victor Stoichita, L'Instauration du Tableau. Métapeinture à l'aube des Temps Modernes, Paris, 1993 ; Geneva, 1999.

My translation. " O facies decora nimis, cuius pulchritudinem admirari non sufficiunt omnia, quibus datur ipsam intueri. In omnibus faciebus videtur facies facierum velata et in aenigmate. Revelate autem non videtur, quamdiu super omnes facies non intratur in quoddam secretum et occultum silentium, ubi nihil est de scientia et conceptu faciei. Haec enim caligo, nebula, tenebra seu ignorantia in quam faciem tuam quaerens subintrat quando omnem scientiam et conceptum transilit, est infra quam non potest facies tua nisi velate reperiri. Ipsa autem caligo revelat ibi esse faciem supra omnia velamenta " (Nicolai de Cusa De visione Dei, ed. Adelaida Dorothea Riemann, Hamburgi, F. Meiner, 2000, VI, §20-21).

Translation of the Jerusalem Bible, Cerf, 1998. In the Vulgate : " cumque ascendisset Moses operuit nubes montem | et habitavit gloria Domini super Sinai tegens illum nube sex diebus septimo autem die vocavit eum de medio caliginis |erat autem species gloriae Domini quasi ignis ardens super verticem montis in conspectu filiorum Israhel | ingressusque Moses medium nebulae ascendit in montem et fuit ibi quadraginta diebus et quadraginta noctibus ". The Vulgate terms, caligo, nebula, are the terms taken up by Nicolas de Cues. Nubes seems reserved for the cloud of Sinai.

See Christian Trottmann, " La coïncidence des opposés dans le De Icona de Nicolas de Cues ", in Nicolas de Cues penseur et artisan de l'unité, ed. David Larre, ENS éditions, 2005, p. 67sq.

" Et animasti me Domine, qui es cibus grandium, ut vim mihi ipsi faciam, quia impossibilitas coincidet cum necessitate. Et repperi locum, in quo revelate reperieris, cinctum contradictorium coincidentia. Et iste est murus paradisi, in quo habitas, cuius portam custodit spiritus altissimus rationis, qui nisi vincatur, non patebit ingressus. Ultra igitur coincidentiam contradictorium videri poteris et nequaquam citra. Si igitur impossibilitas est necessitas in visu tuo, Domine, nihil est, quod visus tuus non videat " (De icona, IX, §37).

I translate. Καὶ γὰρ οὐδὲ δυνατὸν ἑτέρως ἡμῖν ἐπιλάμψαι τὴν θεαρχικὴν ἀκτῖνα μὴ τῇ ποικιλίᾳ τῶν ἱερῶν παραπετασμάτων ἀναγωγικῶς περικεκαλυμμένην καὶ τοῖς καθ' ἡμᾶς προνοίᾳ πατρικῇ συμφυῶς καὶ οἰκείως διεσκευασμένην. (Περὶ τῆς οὐράνιας ἱεράρχιας, chap. 1, §2, 121 b-c)

On the Byzantine notion of economy, see Marie-José Mondzain, Image, icône, économie, Seuil, 1996.

See on Utpictura18 records B1043 to B1045.

Notice B1046.

" advenit ejus Filius cum multitudine angelorum, hac voce eam ad se invitans : Veni, electa mea, ponam in te thronum meum, qui cuncupivi spem tuam. " (her Son came with the multitude of angels, inviting her close to him with these words : Come, my chosen one, I will place my throne in you, I who have longed for your hope). We find the formula with a few variations in Jacques de Voragine : " Iam prior ipse Ihesus inchoavit et dixit : Veni, electa mea, et ponam in te thronum meum, quia concupivi speciem tuam. " (And the first Jesus began and said : Come, my chosen one, and I will place my throne in you, for I have desired your image). See Barbara Fleith, " Le compilateur Jacques de Voragine, in De la sainteté à l'hagiographie : genèse et usage de la Légende dorée, dir. B. Fleith and F. Morenzoni, Droz, 2001, p. 63. We also encounter ponam te in thronum meum, I will place you on my throne, lectio facilior.

The inscription above John's head presents him thus : " Hic est Baptista Johannes, major homine, par angelis, legis summa, Evangelii sacio [sanctio?], Apostolorum vox, silentium prophetarum, lucerna mundi, Domini testis ", this is John the Baptist, greater than man, the equal of angels, sum of the Law, sanctification of the Gospel, voice of the Apostles, silence of the prophets, light of the world, witness of the Lord.

See Valentin Denis, Van Eyck, Arnoldo Mondadori, Milan, 1980, Fernand Nathan, 1982, p. 58 ; James Snyder, Northern Renaissance Art, Harry N. abrams, New York, 1985, p. 92 ; Cyriel Stroo and Maurits Smeyers, " Hubert et Jean van Eyck ", Les Primitifs flamands et leur temps, La Renaissance du livre, 2000, p.300-301...

Nicolas de Cues, preface to the De icona, trans. Michel de Certaux, La Fable mystique. 2, op. cit., p. 71-72.

Understand : the lines drawn between the painting of the Holy Face and each of the monks circling around the painting, in an arc.

Michel de Certeau, La Fable mystique, II, op. cit., p. 80.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Iconologie de la fable mystique. Le retable de Gand à la lumière du De icona de Nicolas de Cues », Fables mystiques. Savoirs, expériences, représentations, du Moyen Âge aux Lumières, dir. Chantal Connochie-Bourgne et Jean-Raymond Fanlo, PUP, coll. Senefiance, 2016, p. 13-25.

Critique et théorie

Archive mise à jour depuis 2008

Critique et théorie

Généalogie médiévale des dispositifs

Entre économie et mimésis, l’allégorie du tabernacle

Trois gouttes de sang sur la neige

Iconologie de la fable mystique

La polémique comme monde

Construire Sénèque

Sémiologie classique

De la vie à l’instant

D'un long silence… Cicéron dans la querelle française des inversions (1667-1751)

La scène et le spectre

Dispositifs contemporains

Résistances de l’écran : Derrida avec Mallarmé

La Guerre des mondes, la rencontre impossible

Dispositifs de récit dans Angélique de Robbe-Grillet

Disposition des lieux, déconstruction des visibilités

Physique de la fiction

Critique de l’antimodernité

Mad men, Les Noces de Figaro

Le champ littéraire face à la globalisation de la fiction

Théorie des dispositifs

Image et subversion. Introduction

Image et subversion. Chapitre 4. Les choses et les objets

Image et subversion. Chapitre 5. Narration, récit, fiction. Incarnat blanc et noir

Biopolitique et déconstruction

Biographie, biologie, biopolitique

Flan de la théorie, théorie du flan

Surveiller et punir

Image et événement