Montage and dismantling of the tableau

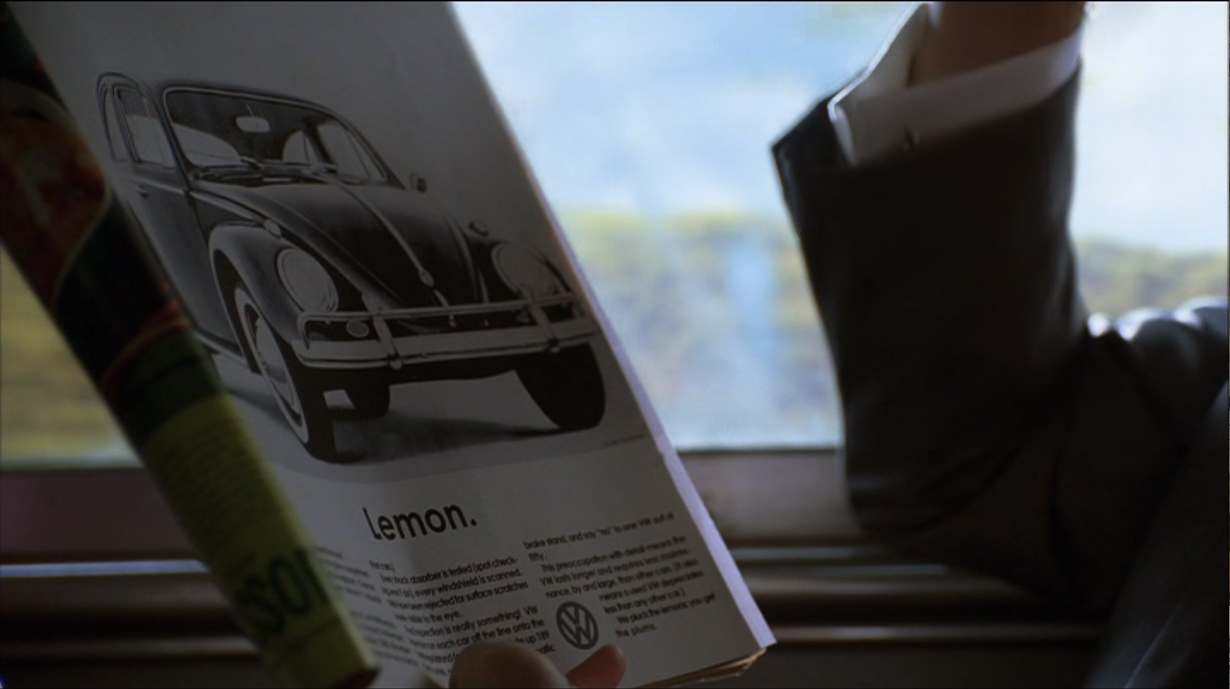

In the beginning, a magazine page held by an elegant man (fig. 1), we see only his right arm leaning against the window sill of a train, and at the end of that arm, protruding from the sleeve of his suit, the musketeer cuff of a crisp white shirt, closed by a cufflink. Behind the glass, the vague green and blue of an indistinct countryside and sky. The same acid green is found on the turned page of the magazine, another advertisement, where vegetables are arranged in a stewpot. The one we're looking at is occupied by a full-page advertisement. It depicts Volkswagen's famous Beetle and bears an enigmatic title, Lemon, made explicit by a text, too briefly shown, in type too small for us to read.

In the next shot (fig. 2), the man appears whole, absorbed in his meditation on this page, comfortably seated, knees crossed, in the train's plum armchair. Don Draper, the brilliant advertising man from the Sterling-Cooper agency, takes a puff on his cigarette, making a tableau : blue suit, plum armchair, green landscape and magazine, blue-striped tie against a metallic beige background, between the beige of the window blind and its brushed aluminum frame. The man steps back from the image on which he is meditating, but which we can no longer see, stepping aside to gently blow out the smoke. This backward movement is countered by the train's advance, which the blurred landscape makes palpable. Perfectly harmonious and balanced, too perfectly perhaps, this painting gives itself away like a glossy image, like a kind of meta-advertisement.

A passenger about to get off the train suddenly jolts Don out of his reverie. His name is Larry Krasinsky, a jovial, expansive, slightly fat, indiscriminately dressed regimental buddy. Krasinsky's familiarity is at odds with the viewer's: he calls him Richard Whitman, not Don Draper. The recognition scene is short-lived; the man has to get off, he gives his card, urges his former comrade-in-war to call him.

Ticket control, a new shot of the Volkswagen advertisement, on which the ticket inspector stops with an amused glance, and we return to the initial tableau, Don Draper leaning against the train window, smoking. But all tranquility, all meditation, is gone his tense, taut face expresses deep annoyance.

The editing of this sequence introduces a parallel between the two paintings the Lemon Beetle on one side, Don Draper at the train window on the other. In both pictures, something doesn't fit, a steeple of the image intrigues, that fascinates and repels, the whole holding together only in the concordance, or at least the proximity of the steeples.

The ad tells a story : this Volkswagen didn't take the boat from Germany to America. You may not have noticed, but the chrome on its bumper has a flaw. Inspector Kurt Kroner has seen it. The customer can rest assured the car he buys will be the fruit of meticulous vigilance. And to conclude : We pluck the lemons ; you get the plums, literally, we pluck the lemons, you get the plums, which could be translated as You reap sweet what we sowed sour. The picking, the acidity of the lemons, is Volkswagen's meticulous work, which is what we see in the image, /// lemon, the eliminated car, what we won't buy. Consumption, the sugar of plums, is the enjoyment promised to the customer, the spectator, and it's again what we see in the image, the beetle, the fruit car, lemon. You don't want this car, and that's why it's been withdrawn from the market. The ad foils your expectations and defense mechanisms; what you want is the fruit, and we make this fruit coincide with the car you're looking at, which becomes desirable because it's been withdrawn. The montage that associates the Beetle as image with the lemon as word makes two parochialisms coincide, the bad car for the good one, the lemon for the plum, the drudgery for the fruit.

Don Draper ponders the Beetle sitting at the window of his train. But he's challenged, recognized as Richard Whitman : the harmonious picture of the elegant man, serene and distinguished, doesn't coincide with the ghost that Richard's name conjures up, with the mystery of that previous, vulgar life, which comes to register in the image as a tense, frowning, collapsing, imposture of type.

But the type emerges paradoxically strengthened: the man we see is not the Don Draper we believe, just as this Beetle is not the Beetle we'll buy but it's precisely by not being what he appears to be, by carrying within him the mystery of a collapsed identity that Don Draper exerts the magnetic fascination that guarantees his success. The montage, which reveals the steeple on which this fascination rests, must therefore itself be backed by a story, a story to tell why Volkswagen promotes its car by showing its flaws, to tell how Richard Whitman became Don Draper. In both cases, the war looms large: the memory of the war arouses a hostile prejudice in the American consumer for a German product, and brings Don Draper back to the moment when he swapped his identity with that of a dead man to be repatriated from the front. The emphasis of fiction shifts from narration to montage; montage presupposes an underlying narration that nourishes, sustains and renews it. But this presupposition tends towards pretext, the link distends : narration is not, or is no longer, the fundamental structure of fiction.

What's the reason for this ? Not the editing, but the dismantling : Larry Krasinsky's irruption dismantles Don Draper. The brainstorming at Don's Sterling-Cooper office dismantles the Volkswagen ad, while the " creatives ", Romano, Kinsey and Crane, struggle to come up with ideas for a Seacore laxative campaign. " This ad, we've been talking about it for a quarter of an hour " remarks Don : criticized, mocked, we always come back to it ; its dismantling is the spring of its effectiveness.

Montage and dismantling of the scenic object

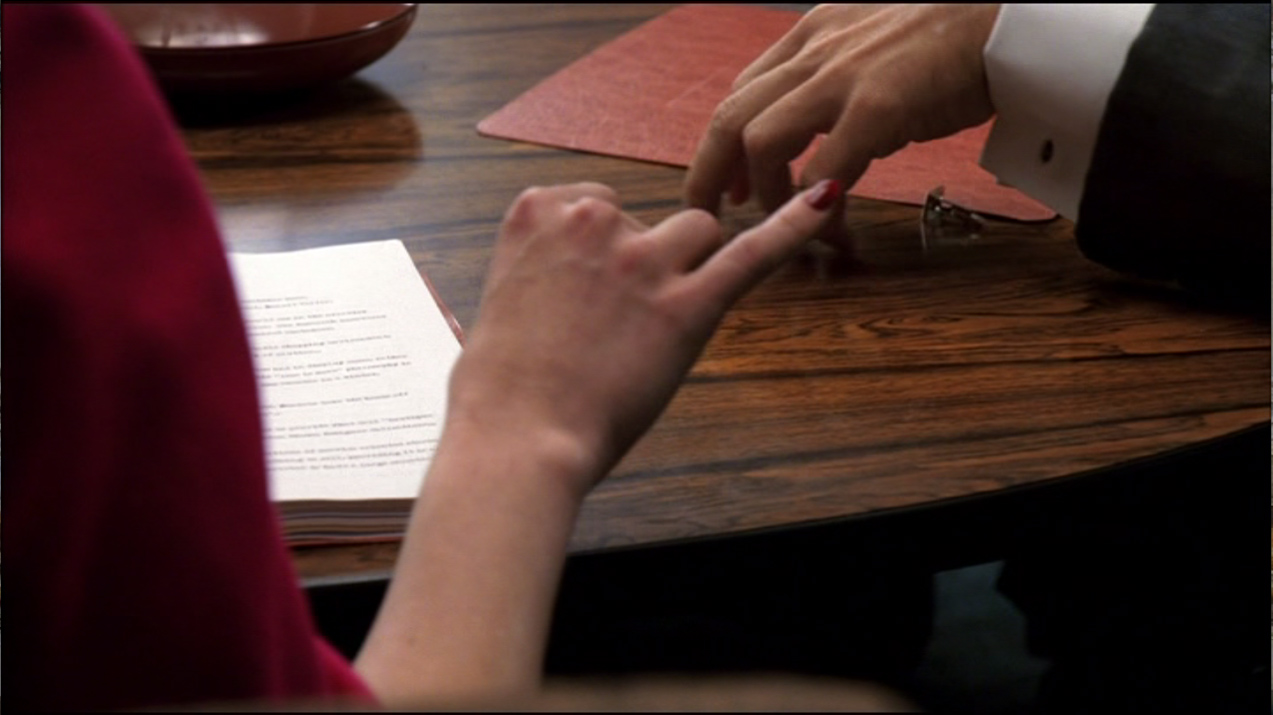

The effectiveness of disassembling sometimes only becomes apparent in the long run, through the enigmatic, unexpected resurgence of a scenic object which, once removed from the stage, changes its meaning, or even becomes incongruous. After the work session in Don's office, Peter Campbell, who has just returned from his honeymoon, takes advantage of his colleagues' departure to have a private conversation with the man he has difficulty accepting as his superior, and whose position he covets. Don doesn't hide his annoyance. He adjusts the sleeves of his jacket and drops one of his cufflinks. The button that falls off, that won't stay on, represents the hollowness, the disjointedness of the scene. Pete Campbell awkwardly counters this mise en défaut of the all-too perfect Don Draper with his new wedding ring, which he shows off, jewel against jewel, jewel that fits against jewel that doesn't fit. The marriage of Pete Campbell, the despised, penniless heir to one of New York's oldest and most prestigious families, to the daughter of a parvenu, is precisely that: a mésalliance.

A few moments later, Rachel Menken, manager of a Fifth Avenue department store, is ushered into the agency's large meeting room, where she is to be presented with a transformation program designed to attract a more upscale clientele. As she listens to the totally platitudinous presentation by the project manager, who hasn't even bothered to visit her store, Don's cufflink falls onto the table right next to her; she flicks it back at him (fig. 3).

The falling button then no longer represents Don Draper's repulsion for Peter Campbell, but both his disinterest in the speech he's attending and his attraction to his neighbor. The speech, like the button, doesn't hold; the button falls towards Rachel and is flicked back from Rachel to Don. Something unravels and something else knots.

That very afternoon, when Don Draper visits Rachel's store, Rachel chooses new cufflinks for him, in the shape of a knight's helmet. By doing so, she signifies the role she assigns him as a servant knight, but also the figure she denies him: perpetually helmeted, Don Draper is the knight without a figure.

Finally, when Don Draper wakes up at home the next morning, between his wife arranging the bedroom curtains and his daughter rushing in overexcited because her birthday is about to be celebrated, and stares at the cufflinks on his bedside table, these cufflinks send him back to Rachel, whom he kissed the day before, to another world of transgressed desires and prohibitions that he chooses to ignore, to cover up, to stifle (fig.4).

However, there is no narrative progression, from the old cufflink that falls off to the new one that holds Don Draper doesn't move from one woman to another, he has always been unfaithful, he is the type of man inhabited by the steeple of disassembly. The cufflink is what holds and what doesn't, the discreet extra of elegance and the secret flaw of the yawning garment, the indentation that opens, but opens without gravity, at the margin, at the anodyne, peripheral place of the wrist.

The cufflink is an innocuous object : it serves as a support for montage only because it itself metaphorizes assembly, juxtaposition, what holds things together. The montage function of the object is more unexpected when the object is incongruous. Returning from his honeymoon, Peter Campbell is astonished by the thoughtfulness of the agency staff, gathered in the open-space of the secretaries, in front of his desk, to welcome him. Only in retrospect does he understand the reason for this interest : when he opens his door, he finds himself face to face with a Chinese family eating their rice in the company of their chickens, much to the hilarity of his colleagues, who have reserved this farce for him (fig. 5). The ambitious Campbell, haughty with the secretaries, always cold or caustic, is thus brutally brought back to reality. /// It's a montage that makes sense by contrasting the characters with the place (the hen on the back of the chair, the rice pot next to the telephone). This squat for laughs is a montage, making sense by contrasting the characters with the place (the hen at the top of the chair back, the rice pot next to the telephone), the scene in the office with the spectators in the open space, the hilarity of the spectators with the bemused fury of Peter Campbell.

But the hen in the foreground somehow continues its own life after this sequence, beyond which it has no reason to exist : when, after the fiasco of the presentation made to Rachel Menken for the renovation of her store, Don escorts her towards the exit, Rachel encounters the hen on her way, heading as she does, in the corridor behind the partition and glass doors, towards the elevator (fig.6). The hen then changes meaning completely. Rachel's fuchsia dress and daring long-haired hat create an effect of provocative ostentation, somewhere between femme fatale and femme facile: the hen is certainly incongruous in front of Rachel, whose path she seems to be clearing, but it is Rachel who forms a tableau behind the hen, hen against hen, like an indictment not of Rachel herself, but of the way people at the agency look at a store manager who is a director, and a Jewish one at that. The hen is Rachel seen as a hen by Sterling Cooper. The hen wandering through Sterling Cooper's glass corridor is a montage that dismantles the play of figures. Rachel hears the message it is in a banal, laborious beige suit, which Don ostensibly notices (" You've changed... "), that she will receive Don, that very afternoon, at the store.

In the foreground on the right an older man, seated, smokes a cigarette he is anonymous. He observes the scene with indifference; he is the indifference of the world. Don stands at the threshold of the glass door, which Rachel crosses. At the threshold of this glass screen, the painting arranges for Don the sublime woman and the hen, the scopic coming and going from one to the other, the possibility of a crossing for this coming and going. The montage holds to this glass wall, beyond which the mystery of the woman is dismantled.

The glass door of Sterling Cooper corresponds to that of the Menken's store, from inside which, in the next sequence, we see Don Draper getting out of a cab (fig 7). We think we see Don through the glass, just as Rachel had disappeared behind Sterling Cooper's glass. Don's silhouette looms transparently behind the letters of the store's name, as if placed behind an Art Nouveau grille or a whimsical hedge, held at a distance therefore, controlled. But in the next shot, Don arrives from the left, and we realize that what we took for transparency was in fact a reflection, that the apparent outside was a door leaf against a wall. The structure of the montage (the inscription Menken's, the glass door of the store, Don, which can be compared to the montage of the first shot of the episode, with the advertising page, the train window, Don) is thwarted by the reflection, the real Don deconstructing, by his emergence from the left, the arrangement of the reflected Don.

Mise en abyme of the montage

Don is always as close as possible to reality, between the flat and the mysterious, between the insignificant and the senseless. In the first episode of the series, where he has to come up with the slogan for the Lucky Strike cigarette campaign, his genius is to stick as close as possible to the reality of the manufacturing process : it's toasted, the tobacco is toasted. His genius is not his own style it's the very genius of advertising, which creates fiction neither outside nor even from its object, but within it, and to do so accompanies, arranges, edits, and therefore dismantles the real.

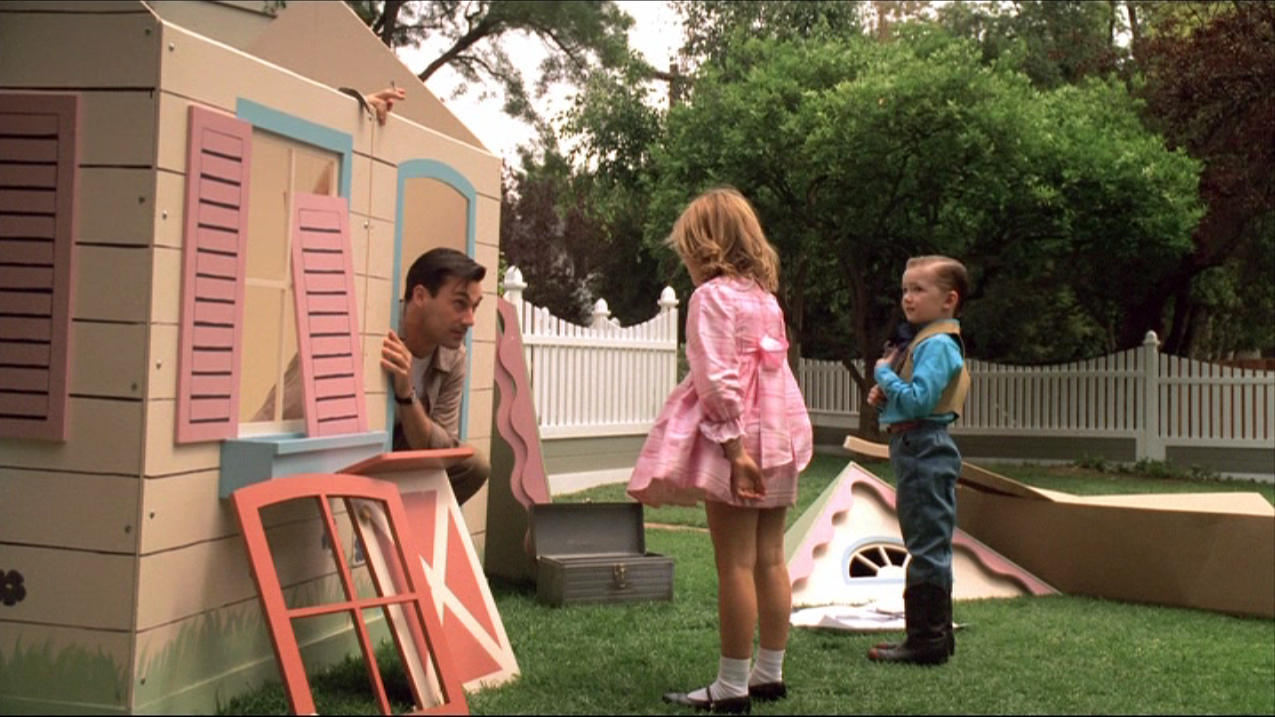

The second part of the episode recounts the following Saturday, devoted to celebrating the birthday of Don and Betty Draper's daughter, Sally, with family and neighbors. Sally's gift is a toy house, which Don is asked to assemble in the garden (fig. 8). The montage of the house constitutes an initial mise en abyme of the episode's sequential montage, itself thematized by the series' subject, advertising, and by its hero, Don Draper, who is a montage of figures.

Don, dressed in chic weekend DIY casual wear, perplexingly reads the house's assembly instructions, crouching between the lid of the packing carton, which reads Girls Playhouse, and the carton itself, where the loose parts are piled. Just behind him, we can make out his khaki toolkit, which forms a graceful cameo from brown to green with his shirt and pants, while the scene is delineated, in the distance, by the new, immaculate white garden fence, behind which, between the trees, we can make out a plush neighboring house.

Don's concentrated crouching posture echoes the liminal one of Don on the train, meditating in front of the Lemon Beetle. The turquoise blue of the leaflet, whose contents we can't see, echoes the blue of the poster on the lid. Don is encircled by what he has to ride, he rides the object in, from the object, he rides it in the uncertainty of being able to ride it. Don's place is the central void of the house, between cardboard and lid, between tools and parts, within the garden fence. Don is going to create the house, an artificial house that is already oppressing him, undoing him, suffocating him. The montage reveals the potentiality of a structure to be made: the obvious remains below the structure, and the obvious overhangs the structure. The vertigo of mise en abyme : it's impossible to decide whether we're being directed towards a takeover or a dispossession.

Sally and her brother Bobby couldn't resist coming to see the progress of the house (fig. 9). Don addresses his daughter from inside the toy house, whose front he holds with his right hand, which is pinching a cigarette: " Normally, you wouldn't see it ". Sally stops at this threshold of invisibility. The editing process is obscene, as if the prohibition of representation has shifted from the trivialized, omnipresent image to the editing, which is not so much its secret as its point of failure. Bobby doesn't look at the house, but at Sally looking at her father, slightly worried, alert to the limit she might cross.

From inside the family home, in the kitchen, Betty and her friend Francine watch Don at work. " What a man ! " exclaims Francine tenderly in front of Betty, proud /// and amused. Cigarette and screwdriver forward, Don mounts the facades, and makes tableau as icon of virility, as facade on facade, ob-scene.

Later in the afternoon, when the guests have arrived, Don has taken refuge in the garden, watching the children play around the toy house. He's soon joined by Helen Bishop, the neighborhood divorcee, literally driven out of the house by the persiflage of the wives' council. " There are some pretty big numbers inside. - It's the same outside." Immediately a silent affinity is established, by juxtaposition of rifts and suffocations. Don and Helen make a tableau from the kitchen for the wives (fig. 10), and the virile obscenity of the tableau this time no longer amuses : it scandalizes.

The montage competes with the scene : from the kitchen, the window with its white muslin curtain and latticework, screens Don and Helen's intimacy surprised by the wives' break-in. This is the archetype of the most topical classical device. Perhaps too much so: this surprised intimacy is itself a fake chromo, an inconsistent advertising pose, mounted on the theatrical facade of the toy house on the left, on the facade of the suddenly inexplicably close neighboring house on the right. What fascinates and oppresses in this picture is the extraordinary proximity of the facades, the crushing of these upside-down silhouettes between, by these facades. In the classical scene, the voyeur, the husband surprising his adulterous wife, is indeed in the position of the women who surprise their supposed lovers from behind, from whom the faces of the figures escape: the voyeur is ultimately the one who sees nothing.

But the scenic device doesn't in principle adopt the voyeur's point of view on the contrary, it reverses it: placing the voyeur at the back of the stage, it reverses the point of view (fig. 11), to offer the viewer the totality of what there is to see, while the body of the crime, the object of curiosity is almost entirely denied to the gaze by which we are nevertheless supposed to become acquainted with it.

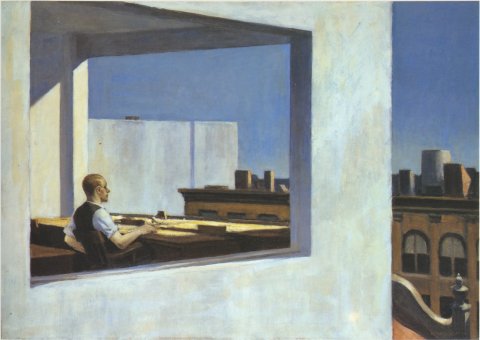

Here, the camera's point of view is that of the wives : we see nothing more. The scenic break-in therefore doesn't deploy a stage, doesn't turn around for the spectators the characters the wives see from behind. These characters, suspended in the vagueness of an objectless reverie, should be facing a view, an expanse, a landscape, a sky, the sea. Instead, facades rise up before them, blinding their vision, oppressing their reverie. Here, the camera is inspired by the windows and facades of Edward Hopper, whose factory maintains, /// perpetuates the empty form, the structure of the scenic device, but evades its content, diverting it into the existential metaphysics of montage, the montage of facades as the dismantling of figures. In Night Windows, in 1928, Hopper takes us inside a bedroom where a woman is undressing, through the wide picture windows of her corner apartment. In Summertime, in 1943, a young girl stands dreamily on the first steps leading up to the entrance to a building. In High Noon, in 1949, the same posture at the threshold, but of a white wooden house as if cut out of the emptiness of the Middle West plain. In Morning sun, 1952, from the bed of her bare bedroom, a woman absorbs herself in empty, vague contemplation of the light streaming in through her wide window. In Office in a small city (fig. 12), 1953, the man seated at his table is as if caught in a vice between the two bay windows of his office. The opening, the light, the space, don't function as the depth of the classical wave that frames the scene, but quite the opposite as flattening, hollowing out, reducing space to an oppressive interplay of surfaces, as assembling and disassembling these surfaces. Mad Men recovers this montage function of absorption, emptiness, vagueness, but it departs a little further from the classical stage, blinding it : we no longer see it, it is no longer delivered to us : not that it is deliverable ; but the stage artifact that slips away from us is only a lure, only a reflection, only a montage effect.

When Betty asks Don to film the birthday party, the camera's play only doubles that of the toy house : the filmed mini-sequences pile up around Don, who is summoned to record them like so many pieces of an impossible-to-assemble puzzle (fig.13). Should we film the hysteria of children running and screaming around the house? Helen's embarrassment at not daring to give herself up to the council of wives, where she knows in advance she'll be torn apart ? The foolishness of husbands imbibing alcohol ? Helen's altercation with Carlton Hanson, Francine's husband, who has come to offer Helen's children the help of a surrogate father, which she interprets, rightly or wrongly, as an offer of adultery ? The tender kiss of another neighboring couple, caught them in a true intimacy that has no place on the anniversary façade ?

Don has turned on the radio, which is playing The Marriage of Figaro, starring Robert Merrill and Joan Sutherland. (Truth be told, while Joan Sutherland sang both the Countess and Cherubino, it was as Figaro in Rossini's Barbier that Merrill shone). In fact, it's Cherubin's aria that we hear, in Act II Scene 3:

Voi che sapete Vous qui savez

Che cosa è amor Ce que c'est que l'amour

Donne, vedetta Belles dames, voyez

S'io l'ho nel cor Si je l'ai dans le cœur.

Quello ch'io provo What I feel,

Vi ridirò I'll tell you

È per me nuovo, It's new to me

Capir nol so. I don't know how to understand it

Chérubin has composed a romance for the Countess, which Suzanne has surprised. Together with the countess, Suzanne forces Chérubin to sing this romance in front of her, while she accompanies him on the guitar. Chérubin declares his love, deferring the knowledge of it to the ladies, who are in love with him. /// gently mock him : Voi che sapete...

Always perfectly smooth, clean, elegant, Cherub's tune resonates with Helen Bishop's sentimental wreckage, but also with Don's existential doubts and cracks. It produces the same face-off as the Lemon Beetle, as the cufflink, as the toy house in pieces. Perhaps it's even this air that drives Helen and Don out of the house. The sequence is saturated with shots whose juxtaposition each time brings into tension a montage that makes sense and a dismantling that points to the emptiness of the characters, caught in the web of a hyper-ritualization of social life. The ritual must be broken: summoned to fetch the cake by Betty, who intends to separate him from Helen, Don leaves, only to return at night. The montage collapses through shot saturation.

The montage cannot therefore be reduced to the structural form of the series. In Mad Men, montage thematizes the subject of the series, and in the process immerses itself in fiction as an object that can itself be taken apart, and makes sense, for the story, to be taken apart. Each time, montage stumbles upon the emptiness, the vagueness, the failure that it brings to light and to work. Another function is therefore at work, upstream of it, overhanging it, organizing the saturation of shots, their collapse. This is the function of the device. This device is not the classical one of the stage, systematically hollowed out, overturned by editing, de-emiotized by the virtualization of the screen, replaced by a glass wall, a façade artifact. Another device is at play, which identifies this figural void it installs with a knowledge of love : Voi che sapete, sings Joan Sutherland and, during the end credits, Frank Sinatra gives the contemporary translation : at the edge of the scene, at its glass threshold, something is said at the edge of the void, something like a P. S. I love you. Perfectly aestheticized, seemingly empty, and yet at the edge of a silent revolt.

Illustrations

All screen captures are from Mad Men, season 1, episode 3, Marriage of Figaro. The series was created and produced by Matthew Weiner, with the first two episodes directed by Alan Taylor, one of the masterminds behind Sopranos. The script for episode 3 is not by Matthew Weiner himself (who only signs or co-signs 7 of the 13 episodes), but by Tom Palmer, and it was directed by Ed Bianchi ; 1st broadcast on AMC August 2, 2007.

The " pilot " episode was shot at Silvercup Studios and various locations in New York. Subsequent episodes were shot at Los Angeles Center studios.

///

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Les Noces de Figaro », Le Montage comme articulation. Unité, séparation, mouvement, dir. Jonathan Degenève et Sylvain Santi, Presses de la Sorbonne nouvelle, 2014, p. 175-188.

Critique et théorie

Archive mise à jour depuis 2008

Critique et théorie

Généalogie médiévale des dispositifs

Entre économie et mimésis, l’allégorie du tabernacle

Trois gouttes de sang sur la neige

Iconologie de la fable mystique

La polémique comme monde

Construire Sénèque

Sémiologie classique

De la vie à l’instant

D'un long silence… Cicéron dans la querelle française des inversions (1667-1751)

La scène et le spectre

Dispositifs contemporains

Résistances de l’écran : Derrida avec Mallarmé

La Guerre des mondes, la rencontre impossible

Dispositifs de récit dans Angélique de Robbe-Grillet

Disposition des lieux, déconstruction des visibilités

Physique de la fiction

Critique de l’antimodernité

Mad men, Les Noces de Figaro

Le champ littéraire face à la globalisation de la fiction

Théorie des dispositifs

Image et subversion. Introduction

Image et subversion. Chapitre 4. Les choses et les objets

Image et subversion. Chapitre 5. Narration, récit, fiction. Incarnat blanc et noir

Biopolitique et déconstruction

Biographie, biologie, biopolitique

Flan de la théorie, théorie du flan

Surveiller et punir

Image et événement