Michel Foucault published Surveiller et punir in 1975, almost fifteen years after his first major book, the Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique (1961). Although the link is not explicitly made, these two investigations respond to each other, and to a certain extent, the challenge of Surveiller et punir is to provide a theoretical response to the methodological problems raised by Histoire de la folie.

I. Purpose of Surveillance and Punishment: a history of the soul

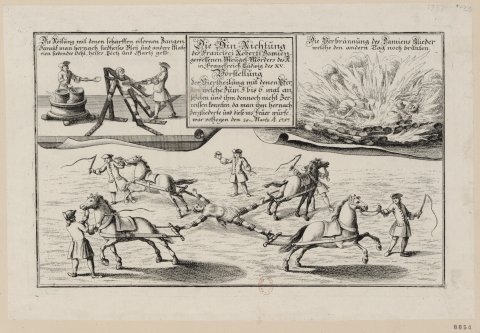

At the start of Surveiller et punir, two examples: on the one hand, the torture of Damiens, the failed assassin of Louis XV in 1757; this is the last great French public torture; on the other, a timetable, dating from 1838, and setting the day for prisoners at the Maison des Jeunes détenus in Paris: the times have changed and are introducing discipline in place of the old scenography of punishment. Between these two realities, these two eras, Michel Foucault intends to describe a history, a passage, an essential transformation.

"The aim of this book: a correlative history of the modern soul and of a new power to judge; a genealogy of the current scientific-judicial complex1."

Objective unclear: what object, concretely, is it describing? It's not exactly punishment, it's not a penal history. In fact, one of the book's aims is precisely to show that punishments are playing an increasingly less important symbolic role in our society: not that they've disappeared, but that they've become shameful, detached as it were from the general social machine, where something else has taken their place. That something else is the prison, which is not just a place where prisoners are punished, but a system for taking control of souls that proves that justice has changed its purpose: torture left its mark on the body of the condemned, marking it with pain, reserving the soul for God's justice. Although prison leaves its mark on the body, it is not the body that it targets, but rather, through the discipline it inflicts on the prisoner, the souls that it intends to control, straighten and reform. Justice no longer ritually repairs the wrong committed; it prepares for reintegration, intends to become pedagogical.

The object of Surveiller et punir has thus changed along the way: from the pain of bodies (the torture) we move on to the hold on souls (the prison), as the birth, the expression of a "new power to judge". The aim is not, however, to describe the judicial system, to trace the history of institutions and laws, or to draw up statistics on convictions, their duration, hierarchy and effectiveness. Michel Foucault's inquiry is in a way sociological: he would rather like to identify, from the techniques and structures of the administrative machine used by the judicial system, how society manages its relationship with individuals. This is what he calls a history of the modern soul, and why he links this history to the emergence of a "new power to judge".

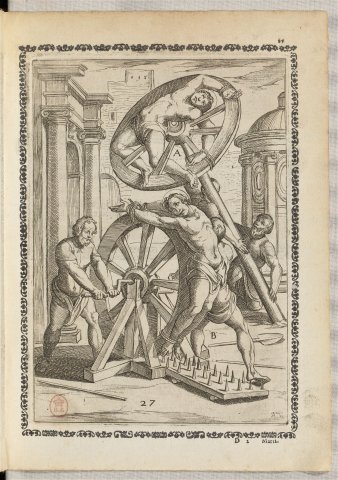

In fact, he refers to this soul essentially as the body. Between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, we move from the body to the soul as the object of the "scientific-judicial complex" that is taking shape. This transition took place through gradual transformations: the former body of the criminal became a sacred body, subjected to the ritual of justice, to the dazzling performance of torture and torment. This brilliance presupposes a theater: the stage is exacerbated by it in the eighteenth century; what it gives to see, the audience it aims at, the effect it expects from its representation become the object of all discourse and attention.

II. Theatricalizing punishment: semiotics of the torture scene

This hyper-theatricalization is in fact a first dematerialization. What counts is no longer the symbolic effect of the suffering inflicted, the brilliance of the torture as a symbol of the power of the avenging prince; it's the imaginary effect of the scene, not the suffering actually given, but the image of the suffering received, the spectacle of which must strike imaginations and serve as an example. The classic martyred body is a glorious body: the saint on the wheel or cut into pieces, the tortured criminal, and even the victims of Sade's libertines, produce immaculate bodies, without a trace of insult, and faces without grimace, impassive or ecstatic. The torture leaves its mark (of glory and infamy) but no trace, or at least none that society wants to see. The transition from the classical glorious body to the post-revolutionary fallen body, disfigured and damaged by avanities, is also the transition from a symbolic performance to an imaginary representation. The sight of this spectacular defilement is unbearable. Thus, the penal code published in the autumn of 1791 reads:

"Article 4. Anyone sentenced to death for the crime of murder, arson or poison, will be taken to the place of execution clad in a red shirt.

The parricide will have his head and face veiled with a black cloth; he will only be uncovered at the moment of execution.

Article 28. Whoever has been sentenced to one of the penalties of irons, confinement in a house of strength, discomfort or detention, before undergoing his sentence, will first be taken to the public square of the town where the indictment jury will have been convened. There, he will be tied to a post placed on a scaffold, where he will remain exposed to public view, for six hours, if he is sentenced to the penalties of irons or confinement in the house of strength; for four hours, if he is sentenced to the penalty of discomfort; for two hours, if he is sentenced to detention. Above his head, on a sign, will be inscribed in large characters his name, profession, domicile, the cause of his condemnation, and the judgment rendered against him2."

On the one hand, everything is organized in view of the edifying spectacle: red shirt for the most serious crimes, installation of a scaffold in the public square, sign noting the culprit of infamy. On the other hand, the bodies of the most infamous criminals, the parricides, are hidden from view: the head and face, covered by a black veil, are only revealed at the moment of execution, which must itself be carried out without duration or pain. The spectacle is virtualized: codified, announced, exemplarized, it must capture the imagination; but, on the spot, there will be nothing left to see.

Justice leaves the age of rites and enters that of representations: it produces and distributes edifying tableaux3. Not the torture itself, but the representation of the punished crime, a representation that makes a sign and enters into a general taxonomy of punishments4, itself modulated by the regime of extenuating or aggravating circumstances: it's no longer the crime that the punishment punishes, but the criminal that the prison rectifies. This rectification is measured on a scale of durations and intensities, according to a reparation system in which the convict's work-value becomes the unit of measurement.

Corporal punishments gradually disappear; the death penalty, while remaining the supreme punishment, survives only as an epure of torment, without suffering, without duration, without apparatus: in fact, in this new economy, it no longer has any reason to exist.

Michel Foucault then notes a paradoxical phenomenon: in the second half of the eighteenth century, all treatises, all proposals for penal reform insist on the necessary spectacular, public, exemplary dimension of punishment. Punishment must be seen as a spectacle, a spectacle that must be a sign in exact correspondence with the crime committed; prisoners must be seen on the roads, engaged in work of public utility, and visiting "men even at the mines, at the works, to contemplate the awful fate of the proscribed5". The representation of punishment must literally inhabit, haunt the public space.

III. The prison revolution: no longer punishing, but reforming

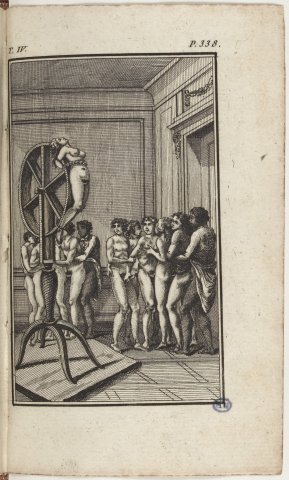

Barely had these reforms been implemented when, in just a few years at the beginning of the nineteenth century, a gigantic effort was made to build prisons: prisoners disappeared from the public space, the spectacle of punishment became impossible, invisible, the whole theatrical system of exemplary representations collapsed and disappeared6.

In fact, the same movement to dematerialize punishments, which had motivated the shift from the discontinuous, punctual ritual brilliance of torments to a generalized management of representations of punishment, theatrical, exemplary, striking the imaginations, now dematerializes the very object of punishment: not the body being made to suffer, but the soul being straightened out. The spectacular stage is then replaced by the closed, invisible space of the prison, with its cells and its system for managing individuals, in other words its discipline, its timetable, its exercises7.

Or this dematerialized management of a now invisible object (the souls of prisoners, the souls of the society that knows, that imagines what the souls of prisoners are subjected to) always manifests itself as a management, an orthopedics of bodies8. The military and pedagogical discipline of the prison is exerted on the bodies, not only by the regulation of a daily schedule, but above all by the subjection to a work, an activity, a profitability that makes each "docile body" a part of the general social machine9.

The body is the central object of Surveillance and Punishment. We start with the suffering body of the supplicant; we arrive at the docile body of the prisoner subjected to penitentiary discipline. The suffering body is a unique body, radically separated from the soul: at the very moment when the executioner inflicts the worst tortures on the condemned, the confessor brings the same condemned man, with all the deference, compassion and Christian humility that his suffering imposes, consolation, comfort and promise of forgiveness10.

By contrast, the docile body of the prisoner is a part of the social machine, a serial object11, articulated to the soul that must be straightened out. Disciplining the body means disciplining the soul, and this discipline consists in integrating the part, the cell, into the general machine. The torture defined a rite; the image of the torture turned this rite into a representation; finally, the implementation of this image as a discipline unfolds the representation into the techno-structure of the prison12. Of course, the exercise of power has always aimed at soul control. But the method of achieving this control has varied. What power acts upon has become dematerialized: what it strikes at, what it shapes, reforms, inflects, constitutes an increasingly continuous, fine, subtle, immaterial mesh of the social body. Punishment is a show of force, a punctual manifestation of the Prince's anger and power. The scene of punishment, ordered according to an exemplary system of punishments, is already a more systematic, regular and continuous implementation of political power. Finally, the prison, thought of as a discipline for integrating docile bodies, is now part of an organic thought of the social body, controlled, reformed, cultivated, valorized, exploited to the fullest.

IV. Emergence of the notion of dispositif

Michel Foucault is not so much sensitive to this dematerialization of control and its instruments, as to the increasing complexity of the apparatus implemented to monitor and punish, as if society had at first been simple, with erratic rituals that no system linked : isn't this the presupposition underlying Foucauldi's formula of a "discontinuous management13" of punishment?

The systematization of rituals is reflected in the promotion of the stage as the central medium for representations of punishment. Whether given to be seen or, subsequently, imagined, the punishment scene makes a sign: it introduces a semiotics of punishment, a system of signs corresponding, as closely as possible, to a taxonomy of crimes. The first general system to be put in place is therefore first and foremost a system of representations; it intends to exercise social control, regulation through representation.

Then comes the third phase, the construction of prisons and the invention of timetables, prison discipline, control and correction strategies. The system no longer manipulates images alone. Codification is aimed at behaviors, activities, exercises, complete control of prisoners' bodies and, from there, of the entire social body, with the development of police, indicators, the management and archiving of their reports, and, dominating this new administrative economy, taste, the Napoleonic aesthetic of detail.

The second phase, of codification, of semiotization, is the structural phase. The third phase, of generalized takeover, is that of the device. At first, the word is used very sparingly. In Chapter I, it appears only once, in connection with the prison:

The third phase is that of generalized control.

"But a punishment like forced labor or even like prison - pure deprivation of freedom - has never functioned without a certain punitive supplement that does indeed concern the body itself: food rationing, sexual deprivation, beatings, dungeons. An unintended but inevitable consequence of confinement? In fact, prison in its most explicit dispositions has always provided a certain measure of bodily suffering. [...] Punishment is difficult to dissociate from additional physical pain. What would an incorporeal punishment be?" (p. 23)

There is a structure, which is that of punishment. Punishment fits into a taxonomy of punishments, itself articulated to a taxonomy of crimes14, according to a semiotic logic ideally matching each signifier (the punishment inflicted, known, public, visible) with a signified (the crime this punishment punishes, concealed, underground, invisible). This semiotic system is based on the theatrical, visual deployment of signifiers, i.e., on the exemplary scenography of punishments: to the scene of the punishment, offered as a spectacle, corresponds the scene of the crime, subtracted, invisible, conjectural15.

Or Michel Foucault notes an essential difference between this ideal functioning of the structure and the actual functioning of punishment and prison, i.e. their historical functioning, noted by experience. This difference between ideal structure and real experience manifests itself in a supplement, which we can grosso modo identify with the body. In addition to the crime it punishes, punishment affects the criminal's body, and this attack on the body ("food rationing, sexual deprivation, beatings, solitary confinement"), intended or not by the law, by the system, demanded by the public, constitutes a supplement.

From this supplement (the word necessarily refers to the notion developed by Jacques Derrida), Michel Foucault's theoretical modeling switches from a thinking of structure to a thinking of device: there was a semiotics of the torture scene, with a structural correspondence of taxonomies (of crimes, of punishments); there will henceforth be prison devices. These dispositifs not only designate, historically, a new era, a new economy of punishment; they also characterize, theoretically, a new stage in Michel Foucault's thought, a step forward in theorizing, an attempt to go beyond structural thinking.

What do these devices, explicit or implicit, of the prison designate? All the concrete, the living, the real that is irreducible to structure. These are the elements of the prisoner's daily life, what Michel Foucault refers to as the body. The device is the structure worked, modified, inflected by the body.

There is a supplement to the structure, and it is this supplement that allows us to access the dimension of the device. In Michel Foucault's analysis, the supplement manifests itself first as a trace, a persistence of the old economy of torture: While torture was eliminated from the arsenal of punishments, and corporal punishment gradually disappeared, old practices and rituals persisted, which no longer made sense in discourse, no longer had any symbolic value, but were maintained as a certain relationship, tolerated and even favored underhand, dirty, shameful, abject, with the prisoners' bodies. The supplement refers back to an origin, to the foundation of punishment: basically, to punish was to supplicate.

But the body's supplement doesn't just refer to an origin that becomes shameful and that good conscience represses. At the same time, it gives rise to new techniques for managing, coercing and normalizing individuals, techniques for which prison becomes the laboratory and model for society as a whole. This body that is reached, no longer in the brilliance of torture, but in the shameful overflow of penitentiary discipline, prepares, orders the new society of control.

"The "reformatories" also set themselves the function, not of erasing a crime, but of preventing it from happening again. They are devices that look to the future, and are set up to block the repetition of the misdeed. [...] The point of application of punishment is not representation, it's the body, it's time, it's everyday gestures and activities; the soul too, but insofar as it is the seat of habits. [...] As for the instruments used, these are no longer representational games that are reinforced and circulated, but forms of coercion, patterns of constraint applied and repeated. Exercises, not signs: schedules, timetables, compulsory movements, regular activities, solitary meditation, joint work, silence, application, respect, good habits. [...] The individual to be corrected must be completely enveloped in the power exercised over him. The imperative of secrecy. (II. Punition, chap. 2, "La douceur des peines", p. 150-153)

This is not a system of representation: it's not a question of striking the spirits, of marking the imagination of the spectators, punctual, of the torture, but of acting continuously, durably, on the bodies of the condemned in order to reform their souls: the space of the prison replaces the scene of the torture, and this space is not given to see from the outside but installed to reform, from the inside. Prison becomes "reformatory".

In general, "Forms of coercion", "patterns of constraint"; in particular, "exercises", "schedules", "compulsory movements", "regular activities": these are the elements, concrete, pragmatic, everyday, that make up the new device.

IV. Generalization of the system

The end of the chapter in "The Gentleness of Punishments", where Foucault properly introduces the notion of dispositif, offers us a kind of recapitulation of the "three ways of organizing the power to punish" that succeeded one another historically and in a way overlapped at the end of the eighteenth century, the first in trace form, the last at its point of emergence:

"The first is the one that was still functioning and based on the old monarchical law. The others both refer to a preventive, utilitarian, corrective conception of a right to punish that would belong to society as a whole; but they are very different from each other at the level of the dispositives they draw.

By schematizing a lot, we can say that, in monarchical law, punishment is a ceremonial of sovereignty; it uses the ritual marks of vengeance that it applies to the body of the condemned; and it deploys in the eyes of the spectator an effect of terror all the more intense for being discontinuous, irregular and always above its own laws, the physical presence of the sovereign and his power.

In the project of the reforming jurists, punishment is a procedure for requalifying individuals as subjects, of law; it uses not marks, but signs, coded sets of representations, whose circulation, and most universal acceptance, the punishment scene must ensure.

Finally in the project of the prison institution that is being developed, punishment is a technique for coercing individuals; it implements procedures for training the body - not signs - with the traces it leaves, in the form of habits, in behavior; and it presupposes the establishment of a specific power to manage punishment.

The sovereign and his force, the social body, the administrative apparatus. The mark, the sign, the trace. Ceremony, representation, exercise. The defeated enemy, the subject of law in the process of requalification, the individual subjected to immediate coercion. The body that is tortured, the soul whose representations are manipulated, the body that is trained: here we have three series of elements that characterize the three devices confronted with each other in the last half of the eighteenth century." (p. 154-15516)

Michel Foucault does not deliberately use the term dispositif as a central concept in his theoretical modeling enterprise. Proof of this is the vacillation we are witnessing: it was initially only to the third phase, to prison devices, that this term was reserved.

Then, at the beginning of the text we've just quoted, it's the last two phases, in contrast to the first, that are characterized by the "devices they outline", devices to which Michel Foucault makes a "project" correspond each time, firstly, "the project of the reforming jurists" (i.e., the creation of exemplary scenes of punishment, integrated into a taxonomy of punishments, a semiotics of punishment), and secondly, "the project of the prison institution" (with its daily exercises, its discipline, its undertaking to reform prisoners). The logic of the project, with its devices, replaces the old logic of law, that "monarchical law" whose exercise, performance, "ceremonial", is dazzling, but punctual, discontinuous.

.Finally, the device ends up encompassing the three phases, considered no longer as three historical, successive phases in the social exercise of punishment, but as three methods, three ways of exercising the power to punish that present themselves simultaneously to the historian's observation when he or she looks at the period at the end of the eighteenth century. These three ways constitute "three devices confronted with each other", "three technologies of power".

Theoretical consequences must be drawn from this evolution of Foucauldian vocabulary: first, it is the gradual realization that there can be no exercise of power without the implementation of a device, whatever that power may be. The primitive idea of a gradual complexification of the instruments of power, of increasingly continuous and intimate surveillance of individuals, of increasingly subtle intervention in conduct, is abandoned in favor of a conception of society, whatever its era, as a system where several modes of surveillance and intervention coexist, or even clash, several "technologies of power", where the traces of the old systems endure, where the discourses and practices of the moment are deployed, where the devices of tomorrow emerge.

.The device then becomes all this, this coexistence, this internal confrontation, this superposition, which is at once a superposition of historical phases, ideological models, systems of representation. This superposition is extremely difficult to think about, because each of the levels involved, while interacting with the other two, can also present itself as an autonomous device. This is why Michel Foucault resorts to successive characterizations:

|

Display 1 (Radiance of torments) |

Feature 2 (Scene of punishment) |

Display 3 (Prison) |

|

|

1 |

The sovereign and his strength |

The social body |

The administrative apparatus |

|

2 |

The brand |

The sign |

The trace |

|

3 |

The ceremony |

The performance |

The exercise |

|

4 |

The defeated enemy |

The subject of law in the process of requalification |

The individual subject to immediate coercion |

|

5 |

The body we torture |

The soul whose representations we manipulate |

The body we train |

Modes of defining the device (Michel Foucault, Surveiller et punir, p. 155)

The device is first defined by the authority that implements it, i.e. by what we might call the subject of the symbolic institution. We can see that for Michel Foucault this authority, this subject, this person in charge becomes more and more disseminated, more and more abstract and impersonal: first the person of the prince, then the entire social body, in whose name justice is exercised, finally the totally impersonal apparatus of administration.

The device is first defined by the authority that implements it, that is, by what we might call the subject of the symbolic institution.

The second mode of definition, or characterization of the device is semiological, and we don't see here that the semiotic structure ceases to be the prerogative of the second phase, theatrical and scenic, in the history of punishment. To the pure semiotics of the exemplary scene promoted in the second half of the 18th century, with its system of signs and its taxonomy, Michel Foucault pairs semiotics operating with elements that can be assimilated to signs, but which are not signs in the strict sense: the marks imprinted on the body at the moment of torture, the traces left by the prison in the prisoner's soul. Here again, we note that the movement is one of dissemination and abstraction: the mark, imprinted in the flesh, becomes stylized and abstracted into a sign, a representation; the visual sign is then abstracted into an invisible, mental trace, which corrects, straightens, mentally reforms the prisoner.

The third mode of definition characterizes the chosen efficacy, the form that the implementation of punishment takes. Here, the movement is not one of abstraction, quite the contrary: what could be more concrete, more visible and material than the use of time, the discipline inflicted on the prisoner? On the other hand, the dissemination is clear: not a dazzling torment that will once and for all strike the spirits, and whose ceremonial will be all the more solemn because the punishment must manifest itself as an exceptional measure; but a representation, i.e. beyond the scene of the punishment itself, the image that insinuates itself into people's minds and remains there, a faint image, but repeated, revived by the daily spectacle of convicts working by the roadside, of convoys leaving for the penal colony. Then, no longer a representation, which establishes a direct link from image to punishment and from punishment to crime, but an exercise, which manifests itself not as punishment, but as a hygiene of life, as a good use of the body. The link between exercise and crime has become so tenuous that this exercise can then serve as a model of military and social organization, independently even of a logic of punishment.

.The fourth mode of definition characterizes the person targeted by punishment. Michel Foucault suggests that as punishment seems to soften, as the body is spared, as corporal punishment is abolished, the person being punished is degraded. In the ceremonial of torture and torment, the torturer and the tortured confront each other almost on the model of the judicial duel, of chivalric combat: torture is a kind of parody of combat, whose outcome is predetermined by the ceremonial, but where, as in combat, there is always the slim possibility of an alternative outcome: if the rope breaks, the crowd calls for the hanged man to be pardoned; if the condemned man does not confess under torture, he can no longer, in principle, be executed. Because he is part of this comedy of combat, the supplicate whose body is degraded retains the nobility of the vanquished enemy. Torture becomes unacceptable in the name of humanity when the victim is no longer perceived as a vanquished, but as a "subject of law". They appear to gain in dignity, but lose in esteem: as subjects of law, they are stripped of their rights as subjects by the Law. And this forfeiture, in prison, authorizes the exercise of immediate coercion: he's no longer a person, he's a cog in the administrative machine; he's no longer a subject, or he's a suspended subject.

Finally, the fifth mode of definition characterizes what is targeted in the person being punished, and we see that Michel Foucault hesitates between the body and the soul. An essential metaphysical hesitation: we've already noted that Foucault often refers to the soul as the body. Indeed, in the exercise of punishment, it is always both body and soul that are targeted.

.The ceremonial of torment does not exclusively target the body: as the account of Damiens' torment that opens Surveiller et punir emphasizes, this ceremonial is twofold. On the one hand, executioners set out to torture the body; on the other, confessors are charged with comforting the soul. The torture offers the condemned man a chance of redemption. If the body of the condemned is a glorious one (ideally without grimace or wounds, glowing), it's because the pain he undergoes not only chastises him before men, but purifies his soul before God. This is why the ceremonial of the torture is not reducible to a spectacle: like the ceremonial of the mass, or of the court, it is not simply addressed to the people as spectators of the supplicated body; before the people, the soul of the supplicated is in representation for God.

And why does the punishment scene suddenly intend to target souls? Because justice is becoming secularized, and the division between human justice, which would deal with bodies, and God's justice, to which souls would be handed over, is losing its meaning. So it's no longer the same souls we're talking about, and Michel Foucault plays on words: the mental representation of punishment as a visual stage is not a spiritual representation. It intends to take control of minds rather than souls. What's more, this takeover involves putting bodies to work: Michel Foucault shows how the representation of the convict at work plays an essential role in these early mind-control projects, and he relates the labor value of the convict's body to the development of capitalism, which places labor at the center of social values and even makes it the standard of all value17. The mental representation of punishment is therefore not simply the virtualization of the torment, which would no longer be carried out but would still be given to imagine; what is imagined changes in nature: we imagine the convict redeeming, at length, his crime through his work; we imagine the body at work; we imagine a lost value that is laboriously reconquered, a "subject in the process of requalification".

As for the exercise of the body that is trained in prison, it is just as much an exercise of the soul, in which we should recall that Michel Foucault incorporates, on the strength of the documents he consulted, "solitary meditation, [...] silence, application, respect, good habits" (p. 152, quoted supra). His model is both that of the Protestant Reformatory and the Jesuit spiritual exercises.

In each of the three phases, then, both body and soul are targeted by the "technology of power" to punish, but each time according to a different articulation: the body to save the soul (phase 1), the soul through the representation of the body (phase 2), the soul through the exercise of the body (phase 3), with all the problems posed by this term soul, which becomes spirit and becomes secularized, not to mention the fact that it is sometimes, in Foucauldian analysis, the soul of the spectator, the audience, sometimes the soul of the punished, the prisoner.

V. Moving beyond structural modelling

Let's recapitulate the five modalities for defining the device envisaged by Michel Foucault: the author of the device, its semiology, its efficacy, the nature of the person it targets, what it targets in that person. The series declines all aspects of the basic actanciel schema:

Subject (S) -- Modalities of action (Function, F) --→ Object (O)

Remind the methodological principle developed by Vladimir Propp in Morphology of the Tale (1928): while folklorists were constructing an anarchic repertoire of tales from all over the world, whose empirical types overlapped and did not logically articulate, Propp proposes to reduce the narrative structure of all tales to a single type18, in which he will distinguish a limited number of character functions, these functions (and not the story itself) forming the fundamental basis of the tale. The methodological revolution represented by this new approach to the tale, combined with the rise of linguistics, paved the way for structuralism.

Michel Foucault distinguishes between characters and functions19, which vary from a common narrative structure: a criminal commits a crime and is punished. But the person who punishes him varies, as does the manner of punishment, which itself characterizes that person's function. What's more, the punishment is aimed not only at the criminal, but also at the public to whom he is made a spectacle, or represented. Punishment therefore fulfils a certain function for those to whom it is addressed. The basic schema for defining this function is that of speech, as modeled by Jacobson: one person (S) addresses another person (O) and symbolically transforms them through their speech (F).

Michel Foucault thus begins by theorizing the dispositif as an actanciel schema. This "technology of power", this "technico-political register", this grip "inside very tight powers, which impose constraints, prohibitions or obligations" (p. 160-1), this "system of subjugation", this "political technology of the body" that "is made up of parts and pieces", this "microphysics of power that apparatuses and institutions bring into play" (p. 34-5), the whole nebula of the device always boils down to a subject who subjugates an object using a technique, the whole constituting a variation in the social structure.

But precisely what the device introduces in relation to the clear structural schematization is the nebulous dimension: the subject is not exactly a subject, but rather a dissemination, a dissolution of the subject (the prince in the absence of the prince, the abstraction of the social body, the depersonalization of the administration) ; the object is not exactly a person, but the uncertain relationship, in this person, between body and soul, and the vacillation, to identify this person, between the directly punished condemned and the indirectly targeted public; finally, the function that this technique implements defines a semiology that is not exactly a semiotics, with signs that were initially marks and tend to dissolve into traces.

The device disseminates the structure of the actantial schema that nonetheless gave it its primitive form and delimited its field of activity: a history of the soul that would be a history of the body in its relationship with the symbolic institution, with "the power to judge".

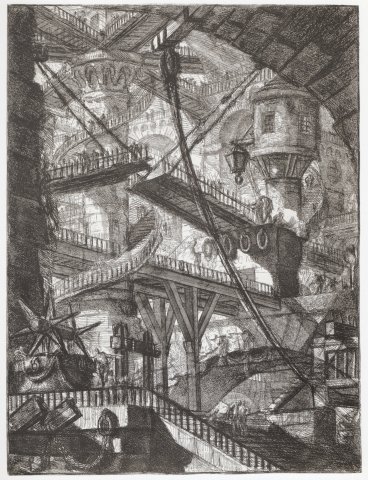

As this structure disseminates and becomes nebulous, a new, visual, modeling principle emerges. We need only be guided by the way Michel Foucault uses the word "dispositif", which reappears in the chapter on "Les moyens du bon dressement" (III, 2):

"The exercise of discipline presupposes a device that constrains through the play of the gaze: an apparatus in which the techniques that allow us to see induce the effects of power, and in which, in return, the means of coercion make those on whom they are applied clearly visible. [...] Alongside the great technology of glasses, lenses and beams of light, which became part of the foundation of new physics and cosmology, there were the small techniques of multiple and interwoven surveillance, the gazes that had to see without being seen; an obscure art of light and the visible prepared, in a muted way, a new knowledge about man, through techniques to subjugate him and procedures to use him.

These "observatories" have an almost ideal model: the military camp. [...] In the perfect camp, all power would be exercised through the mere play of exact surveillance; and every glance would be a piece in the overall workings of power."(p. 201)

In fact, from the outset, alongside the grand ceremonial of the supplications, then alongside the exemplary scenes and tableaux offered in representation, the shocking, massive device of punishment was doubled by a disseminated, discreet, almost elusive device of surveillance. Punishment may or may not be visible; surveillance is, at all times and in all places, an optical device, unregulated by any linguistic modeling, and radically outside the scope of structural narrativity. A paradigm shift.

This device is not just visual and optical. It is radically anti-theatrical: the very opposite of the torture scene. Whereas the stage focuses the audience's attention on an increasingly unified, centralized, clarified and simplified object (in the theater, the rule of the three unities; on the scaffold, the singularizing exemplarity of punishment), the disciplines of surveillance centralize the observer (the voyeur of painters and novelists; the overseer of schools, camps, prisons) and disseminate the thing seen (all the cells of a prison, all the students, all the soldiers).

For this reason, Michel Foucault speaks of an "obscure art of light": a paradoxical device, which multiplies visibilities, but immerses itself in shadow. You have to see everything, but you can't be seen. This device recovers the structural organization of taxonomies: it regulates, classifies and rates the individuals it observes, inscribing them as signs in the vast system of generalized surveillance. But this structure is no longer the form, the global model of social and symbolic organization. The structure, the taxonomy, the system of signs are governed by the gaze, by the space in which this gaze is positioned, by the architecture of the place. The real no longer manifests itself primarily as narrative, but as the installation of a gaze in places. Such is the paradigmatic revolution introduced by the emergence and generalization of the device as an instrument of analysis.

.

Notes

Michel Foucault, Surveiller et punir, Gallimard, 1975 ; Tel, 1993, p. 30.

Michel Foucault prefers to cite the Code de sûreté publique of 1807, which imagines emblems in place of signs (Surveiller et punir, p. 131).

For example, through stories to children, in Servan (1767, see Surveiller et punir, p. 133)

On "the double taxonomy of punishments and crimes", see Surveiller et punir, p. 118.

Brissot, Théorie des lois criminelles, 1781, quoted in Surveiller et punir, p. 132, and more generally p. 133-134 on "the theaters of daily punishment".

"In place of this punitive theater, which was dreamed of in the eighteenth century, and which would have acted essentially on the minds of those subject to punishment, has come the great uniform apparatus of prisons, whose network of immense buildings will spread throughout France and Europe." (Surveiller et punir, p. 137)

"Disciplines in organizing "cells", "squares" and "ranks" fabricate complex spaces: at once architectural, functional and hierarchical. [...] they cut out individual segments and establish operative links; they mark places and indicate values; they guarantee individual obedience, but also a better economy of time and gestures." (Surveiller et punir, p. 173) Michel Foucault identifies the space of the school, the military camp and the prison, as they were constituted during the nineteenth century, with this model.

"a concerted orthopedics applied to the guilty" (p. 154).

"To each individual his place, and in each location, an individual. Avoid group distributions; break down collective settlements; analyze confused, massive or elusive pluralities. Disciplinary space tends to be divided into as many parcels as there are bodies or elements to be distributed. We need to cancel out the effects of indecisive distribution, the uncontrolled disappearance of individuals, their diffuse circulation, their unusable and dangerous coagulation; a tactic of anti-desertion, anti-coagulation, anti-agglomeration. The aim is to establish presence and absence, to know where and how to find individuals, to set up useful communications, to interrupt others, to be able to monitor each individual's conduct at all times, to assess it, to sanction it, to measure qualities or merits. Procedure, then, to know, to master and to use. Discipline organizes an analytical space." (Surveillance and Punishment, p. 168)

"The spectators were greatly edified by the solicitude of the parish priest of Saint-Paul, who despite his great age lost no moment in consoling the patient. [...] The confessors approached him several times and spoke to him for a long time; he willingly kissed the crucifix they presented to him; he stretched out his lips and always said: "Pardon, Seigneur." [...] The confessors who returned spoke to him again. He said to them (I heard him): "Fuck me, Gentlemen." The Sieur Curé de Saint-Paul not having dared, the Sieur de Marsilly passed under the rope on his left arm and was kissed on the forehead. The executors joined in, and Damiens told them not to swear, to do their job, that he had no grudge against them; asked them to pray to God for him, and recommended that the curé de Saint-Paul pray for him at the first mass." (Account of the execution of Damiens, Gazette d'Amsterdam, 1er April 1757; Surveiller et punir, p. 10-11).

See p. 172, "l'organisation d'un espace sériel" (in the school) and p. 188, "la mise en série des activités successives", "un temps social de type sériel".

Michel Foucault doesn't immediately use the term dispositif: "all the apparatus that has developed over the years around the application of sentences" (p. 29); "to make non-legal elements function within the penal operation" (p. 30); "to seek if there is not a common matrix [...]; in short, to place the technology of power at the principle" (p. 31); "to analyze rather the punitive concrete systems" (p. 32); "the body [...] is caught up in a system of subjugationwhere need is also a political instrument carefully arranged, calculated and used" (p. 34); "the political technology of the body [...], this diffuse technology" (ibid.); "a microphysics of power that apparatuses and institutions bring into play" (p. 35); "a mode of internal regulation of power" (p. 47); "conceiving torture [...] as a political operator" (p. 65); "a certain mechanics of power" (p. 69); "the economy general of torment" (p. 71); "the mechanism of punishment" (p. 74); "the penal machinery" (p. 76); "an economy of punishment. [...] the crisis of this economy" (p. 89); "a tighter penal squaring of the social body" (p. 93, see p. 104); "a bad economy of power [...], a poorly regulated distribution" (p. 95); "a regular function, coextensive with society" (p. 98); "a penal system must be conceived as an apparatus for differentially managing illegalisms" (p. 106); "the semio-technique with which we try to arm the power to punish" (p. 112).

Michel Foucault first speaks of "irregular justice" (p. 93-94). Then: "The form of monarchical sovereignty while placing on the sovereign's side the overload of a dazzling, unlimited, personal, irregular and discontinuous power, left on the subjects' side free room for constant illegalism" (p. 104) The nineteenth-century prison on the contrary organizes "an intense, continuous control" (p. 205);

Surveillance and Punishment, p. 118.

From this perspective, Michel Foucault evokes the birth of detective literature: "we have passed from the statement of facts or el'aveu to the slow process of discovery; from the moment of torture to the phase of investigation; from the physical confrontation with power to the intellectual struggle between criminal and investigator" (p. 82).

This is me underlining and introducing the division into paragraphs.

On "public works as one of the best possible punishments" for pre-revolutionary reformers, see Surveillance and Punishment, p. 129.

Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Tale, Seuil, 1965, Points, 1973, p. 33.

On the device as function: "integrating into the disciplinary device as a function that increases its possible effects. It needs to break down its instances, but to increase its producing function." (III, 2, p. 205, on pyramidal architecture as a supplement to the disciplinary device.)

Critique et théorie

Archive mise à jour depuis 2008

Critique et théorie

Généalogie médiévale des dispositifs

Entre économie et mimésis, l’allégorie du tabernacle

Trois gouttes de sang sur la neige

Iconologie de la fable mystique

La polémique comme monde

Construire Sénèque

Sémiologie classique

De la vie à l’instant

D'un long silence… Cicéron dans la querelle française des inversions (1667-1751)

La scène et le spectre

Dispositifs contemporains

Résistances de l’écran : Derrida avec Mallarmé

La Guerre des mondes, la rencontre impossible

Dispositifs de récit dans Angélique de Robbe-Grillet

Disposition des lieux, déconstruction des visibilités

Physique de la fiction

Critique de l’antimodernité

Mad men, Les Noces de Figaro

Le champ littéraire face à la globalisation de la fiction

Théorie des dispositifs

Image et subversion. Introduction

Image et subversion. Chapitre 4. Les choses et les objets

Image et subversion. Chapitre 5. Narration, récit, fiction. Incarnat blanc et noir

Biopolitique et déconstruction

Biographie, biologie, biopolitique

Flan de la théorie, théorie du flan

Surveiller et punir

Image et événement