The scopic dimension of the device manifests itself in what, in the scene, makes a tableau: all of a sudden, it's all we see; all the discourses, all the expected structures fall away, everything reconfigures itself around it. The scopic crystallizes another meaning: it is the effect of the scene for the eye, outside any spatial setting, any framing, any rationalization of a meaning.

Scopic and re-volte

The scopic dimension abolishes, or suspends, the eye's distance from the scenic object (see this notion). It thus introduces another way of functioning for the eye, more archaic than that of the distanced gaze, which reads and decodes. The scopic fascinates and/or horrifies: the scopic effect is unstable and reversible. Through it, in the scene, in the painting, something turns upside down, re-volts. This phenomenon must be considered in its two dimensions, phenomenological and semiological.

1. In the phenomenology of the eye and the gaze, the scopic is equivalent to what M. Merleau-Ponty designates as le chiasme du visible, or the finger-of-glove reversal of the gaze:

"As soon as I see, the vision must be doubled by a complementary vision or another vision: myself seen from the outside, as another would see me, installed in the middle of the visible [...]. He who sees can only possess the visible if he is possessed by it, if he is of it, [...] if he is one of the visible, capable, by a singular reversal, of seeing them, he who is one of them. (Le Visible et l'invisible, "L'entrelacs - le chiasme", Tel Gallimard, pp. 177-178.)

At the moment when the distance between the subject looking and the object looked at is abolished, the subject himself becomes an object and experiences a reversal: behold, the painting looks at him, the scene invades him, submerges him; the spectator, the reader become the actors, while the object looked at accompanies this reversal, becomes its witness. The scopic is thus the experience of an envelopment; distance falls, but at the same time awareness of distance (I look, I am looked at) has never been so great.

.2. But Merleau Ponty himself points out that such phenomenological experience has repercussions for meaning, which is not simply intended to be deciphered, understood, but welcomed, "or, as we say so well, entendu" (see the preface to La Lettre sur les sourds by Diderot). The envelopment that characterizes the experience of the gaze is then reflected in the very workings of language and signification. Merleau-Ponty died before completing Le Visible et l'invisible, but Lacan continued this reflection (Seminar XI), which he had initiated for his part with the notion of pas-de-sens (Seminar V on the Freudian witz): the pas-de-sens is, as it were, the scopic effect of the text. A semantic short-circuit occurs: what is said has no meaning, and suddenly gives the pure signifier to be seen and heard. Since there is no meaning, language regresses, becoming noise again; it is this noise that we hear, and which is the basis of language. This is the archaic experience of the linguistic bath, of being enveloped in speech. Then things are reconfigured differently, another, transversal, rebellious sense is put in place (what R. Barthes calls the "obtuse sense", or "third sense", see Critical Essays III), which makes Lacan say that pas-de-sens is not nonsense, but the establishment of a step, of that connection, that junction necessary to, in an electrical cricuit, establish the disturbance of the short-circuit. (Seminar V, pp. 98-99.)

Scopic crystallization

Then the device shifts from a theatrical organization, based on spatial setting, distance, differentiation of subject and object (everything taken care of by the geometrical dimension), to an indexical organization, based on crystallization around a "something", detail, supplement, undefined feeling, scenic object. From the Renaissance onwards, the scopic dimension is interposed between the geometrical and the symbolic, which it articulates, but historically it is led to assume an ever-greater semiological function, until it occupies the foreground from the end of the eighteenth century onwards. Crystallization then becomes an essential process of signification, competing with the traditional process of symbolization, based on the cut, distance and mediation of symbolic codes.

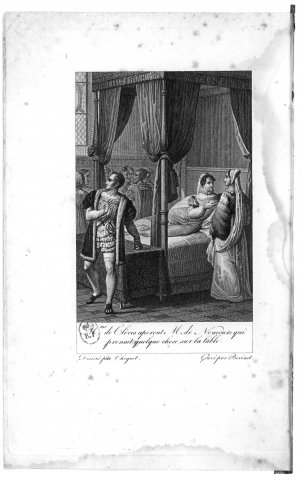

Let's take an example from Mme de Lafayette's La Princesse de Clèves: the portrait scene is ordered around a particularly elaborate scopic effect. In the engraving above, the designer has captured the moment when Mme de Clèves sees the Duc de Nemours taking "something" from the table. The object is none other than his portrait in miniature, through which Nemours can, transgressively, be looked at by the woman he loves: the scene is built on the reversal of the viewer/viewed relationship. Mme de Clèves leaves the established circle of gazes (her conversation with the Dauphine). When she looks at Nemours, her gaze encounters desire and transgression. The object stolen from her is herself: stealing the portrait, M. de Nemours in a way steals Mme de Clèves' eye, he monopolizes it, subtracting it: this is scopic neantization. Through this gesture, Mme de Clèves herself becomes an object of gaze. She, who looks, is equivalent to the portrait, which will be looked at; she looks at what will be looked at (the portrait), looking at the one she looks at (Nemours). Mme de Clèves is overcome with horror at what is happening before her eyes, a veritable theft of herself, over which she has no control. But if she is inwardly indignant, isn't it at the same time in the enjoyment of seeing a desire manifested with impunity that she cannot approve of, but which she shares?

The illustrator has placed Nemours on the left in such a way that he turns away from Mme de Clèves, on the far right, and the Dauphine, on the bed. Nemours is supposed to steal the portrait with an air of nothingness; it's a question of representing this "air of nothingness". But Mme de Clèves also catches Nemours "looking like nothing": propriety forbids him to show the slightest emotion. These two "airs de rien" do not have the same meaning at all; symbolically, they are disjointed. But, in the image, they do somehow meet: see how the postures of Nemours on the left and Mme de Clèves on the right resemble each other. This resemblance makes no sense: what's the connection between the strategy of a thief and the forbidden confusion of a virtuous lady? But at the same time, the profound meaning of the scene lies entirely in the identity of the two "airs de rien": Nemours and Mme de Clèves are united by the same passion, and paradoxically this scene seals this union, this fusion of the two lovers. This is another meaning, which the text does not make explicit, but which nevertheless conditions it. The connection, the junction that the eye makes between the two characters' postures, establishes the scopic crystallization and constitutes the scene's "pas-de-sens".

Critique et théorie

Archive mise à jour depuis 2008

Critique et théorie

Généalogie médiévale des dispositifs

Entre économie et mimésis, l’allégorie du tabernacle

Trois gouttes de sang sur la neige

Iconologie de la fable mystique

La polémique comme monde

Construire Sénèque

Sémiologie classique

De la vie à l’instant

D'un long silence… Cicéron dans la querelle française des inversions (1667-1751)

La scène et le spectre

Dispositifs contemporains

Résistances de l’écran : Derrida avec Mallarmé

La Guerre des mondes, la rencontre impossible

Dispositifs de récit dans Angélique de Robbe-Grillet

Disposition des lieux, déconstruction des visibilités

Physique de la fiction

Critique de l’antimodernité

Mad men, Les Noces de Figaro

Le champ littéraire face à la globalisation de la fiction

Théorie des dispositifs

Image et subversion. Introduction

Image et subversion. Chapitre 4. Les choses et les objets

Image et subversion. Chapitre 5. Narration, récit, fiction. Incarnat blanc et noir

Biopolitique et déconstruction

Biographie, biologie, biopolitique

Flan de la théorie, théorie du flan

Surveiller et punir

Image et événement