The device: a contemporary reality and challenge

Fortune of the word

The word device is encountered everywhere today. Has a catastrophe occurred? The government, the public authorities, the city or the region set up a device for help, reception, rescue, emergency, safety... Sometimes the device is preventive: this museum has a surveillance device; for this school, in case of fire, an evacuation device has been set up; this chainsaw has a power-down device...

The device guards against the outbursts of reality. It re-establishes order in a situation that is out of the ordinary, it reduces, curbs what threatens the natural order, the public order, the instituted order. Prison device, law enforcement device, repressive device: the device has a good face and a bad face; it lends a hand in disaster, but annihilates in revolt. The dispositif is an alternative structure, an emergency institution, with the advantages and disadvantages of any regime of exception.

The notion of the dispositif plays an essential role in the development of a theory of representation, for the dispositif articulates order with disorder, the mechanical efficiency of a strong symbolic structure with the flexibility of a pragmatic, concrete, adaptable implementation. To understand the theoretical issues involved in using this notion, we need to look back: since the 1960s, we've seen two opposing ways of looking at representation, or more precisely, two extreme and irreducible tendencies.

.The historical, or positive, approach

The first, inherited from positivism, rejects all theoretical modeling: every work of art, every literary text has its history, its genesis, its object, about which the researcher sets himself the task of collating objective data. Inevitably, such work concludes with the singularity of its object. The researcher locks himself into this singularity, proclaiming himself the specialist, and ends up unable to communicate with his neighbor, whose object is slightly different. Aware of the danger of disciplinary fragmentation that it carries with it, positive science tries to remedy this by carrying out vast classifications, by period, by genre, by medium, by current of thought, by style: the corpus, the database are its obsessions.

The structural approach

The second way of looking at representation is inherited from structuralism. Placing the history of men and ideas in the background, it emphasizes the internal organization of the work, for which it seeks to identify general laws, common patterns. The perverse effect of the structural method is exactly the opposite of that of the positive method: here, the singularity of the object risks being crushed in favor of highly abstract general models, necessarily vague or false in the detail of their application. But above all, the work appears cut off from the context that produced it, which, in another way, also results in the researcher being locked into the singularity of his object. The heirs of structuralism have attempted to remedy this in their own way, by broadening their object of study, from text to paratext and hypotext, from painting to its frame and non-figurative margins.

Contemporary demands

But neither the obsession with the index card nor the wandering off into the margins responds to the reality of the problem that is posed today to the study of representations: a representation is the articulation of a structure to the real, of order to disorder. Contemporary art, with its installations and unstructured scenic spaces, and the new media of representation, ever more portable, adaptable and transposable, call into question the status of the work, the contours of the art object, and the boundaries of representation. Today, it is no longer possible to consider representation as an object with a given, stable epistemological status. The new interactions between reality and representation that the contemporary era has brought about, and the importance it gives to the heterogeneity of the space of representation, lead us to reconsider the question for earlier eras: looking at a painting or reading a scene from a novel is not, and never has been, a spectator or a reader on the one hand, and a painting or a book on the other. A mixed space is created at the moment of aesthetic consumption: this consumption partly escapes the artist's control; it introduces disorder, which the creator anticipates and incorporates into the work. To this disorder, the work provides a response; faced with it, it constitutes its device, a device of representation.

Presentational device: internal organization and systems of articulation

The three levels that constitute a device

Concretely, what is a representation device?

A device is first and foremost a space, and a concrete, posited space, assumed by the fiction, i.e. generally a place with characters. The space of representation constitutes the geometrical dimension of the device. We say that the space of representation is supposed by fiction: fiction is not representation; it pre-exists it, or is supposed to pre-exist it. In painting, fiction is the subject that the painter takes upon himself to represent. The ordinary case is that of a subject that the painter does not invent, but draws from the common pot of culture, from the Bible, from mythology, from the great literary texts. Racine, Corneille and Molière often depict a subject taken from ancient history (Tacitus, Titus Live, Suetonius), Homer, Virgil or the great Greek and Latin playwrights, in exactly the same way as contemporary painters. We must never forget that genre painting, that literature of invention (novels, for example) are initially nothing more than slightly eccentric extrapolations of this norm: even when the creator does not adapt a really pre-existing subject, it is from a virtually pre-existing model that he works, because it is this way of working that constitutes the norm against which always, even in revolt and subversion, he defines himself.

Space, in a performance device, is therefore not just any space. It is motivated by fiction, and is thus installed to make sense. More precisely, the organization of this space is an organization that makes sense from the outset, even before a discourse accounts for it. The signifying organization of space constitutes the symbolic dimension of the representational device. A well-known example of such a signifying organization of space is the landscape-state of mind dear to the Romantics.

So, to constitute a device, we need to articulate a space (dimension géométrale), the heterogeneity of a real, to a signifying organization (dimension symbolique), to the homogeneity of a code. This articulation, this superposition must be implemented, or mise en abyme, in the representation for the vague awareness of the device's existence to be born, to be produced. This vague awareness is very important: it conditions aesthetic pleasure, which is born of respect for this double constraint. Representation is ordered and it represents disorder; it welcomes the catastrophe of the real and it provides a response to this catastrophe.

This articulation, this double constraint, is realized in a third dimension of the device, which is the imaginary, or scopic dimension: a device disposes for someone, for an outside spectator. It thus establishes, in front of the image, a distance, the possibility of a point of view. There is no device without the distance, facing it, of a gaze. This gaze is responsible for superimposing, for making the geometric organization (what's laid out in front of it) and the symbolic organization (the meaning of the image) coincide. It does so in the flash of a moment, the moment of scopic crystallization. Scopic crystallization is prepared in the representation, even if it only takes place outside it, with the viewer or reader, at the moment of aesthetic consumption. Because there is this internal, prepared objective data, and this external, random subjective data, we have spoken of mise en abyme. Mise en abyme is, in effect, a way of representing an external relationship within, for example by staging a painted spectator inside the painted scene, watching what's going on in the same way as the real spectator who, from the outside, will be looking at the whole canvas.

On the other hand, we were led to distinguish two types of device.

Articulation through the screen: the stage device

The stage device is the canonical device that orders classical history painting and the novel scene from the 16th to the 19th century. It operates the articulation between space and signifying organization by means of what we have called the screen of representation.

Articulation through the supplement: the narrative device

The narrative device is more difficult to apprehend because, although it implements the same levels - geometrical, scopic and symbolic - and articulates in the same way order and disorder, a homogeneous system of signification and heterogeneous data from reality, it conceals itself from the gaze and even constitutes itself essentially on the basis of its invisibility. Indeed, this is its fundamental defining feature: whereas the stage device allows the object of representation to be seen, the narrative device takes note of the fact that this object cannot be seen, and sets up, to palliate this impossibility, possibly to attempt to reduce it, the supplement of a narrative.

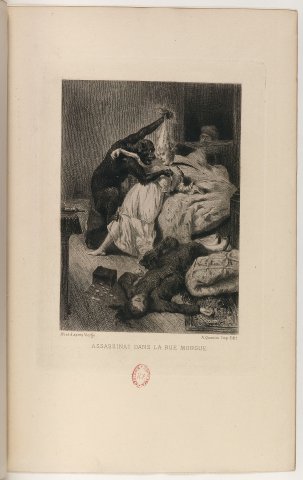

An example: Double murder in the Rue Morgue

Let's take a canonical example: in Double Assassination in the Rue Morgue, Edgard Poe's short story that founded the detective novel genre, not only has no one seen the murder scene, but we can't understand how the murderer was able to enter the bedroom of the two murdered women and then escape, since the door remained hermetically sealed. Invisible, impossible, the scene cannot be represented.

From this unrepresentable object, the murder scene, the narrative constituted by Edgar Poe's short story presents itself as a supplement to the scene: it simultaneously posits the failure of its representation (contradictory or aberrant testimonies, stalled investigation) and the alternative represented by Dupin, the eccentric but brilliant detective. Dupin won't start from the data of reality, which are disappointing and mute for lack of an interpretive model to exploit them. It's this disappointment that needs to be turned on its head, by reversing the implicit assumptions on which witness testimony and investigations have hitherto been based: there was no break-in at the door because the intruder didn't enter through it; the witnesses didn't understand the intruder's language through the door, because it wasn't a language. The negation of the door, leads Dupin to the window; the negation of the language leads him to assume that the murderer is not a human, but an animal.

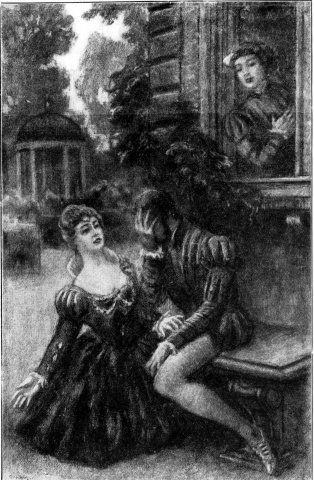

At the end of the short story, the sailor who owns the murderous orangutan confesses that he witnessed the scene from the inside facade of the house, that he had managed to climb up to the height of the window, without however managing to penetrate like the animal inside the house. Edgar Poe thus re-establishes in extremis the scenic device: a spectator breaks in (here through the window overlooking the courtyard) to see what no one should have seen and, through this break-in, through his intermediary, gives the public, the reader, a view of a space a priori closed to the outside gaze. The novella thus pits the two devices against each other: the stage device, which makes the murder visible and explains it through the sailor's gaze-witness; the narrative device, which makes up for the invisibility of the scene through Dupin's logical reasoning, which reconstitutes reality through the negation of the realities gathered at the start of the investigation.

Structure and history of the device

Competition of the two devices

This example shows that the differentiation between stage device and narrative device cannot be reduced either to a question of era (stage until the 18th century, narrative from the 19th century onwards), or to a question of genre (stage in painting, narrative in literature). A single work, in this case Poe's short story, can implement both devices concurrently. In a completely different style, Girolamo Porro's engravings for the Roland furieux implement a hybrid device, which is part stage and part narrative.

The distinction between stage device and narrative device is therefore not a distinction between two distinctly separate categories or modes of representation. It's all a question of implementation, which takes place differently. In fact, in both cases, the chamber is the ideal form to which the geometrical dimension of the device reduces the space of representation. When this room is open, it gives rise to a scene; when it is closed, this closure is replaced by a narrative. But the facts of the fiction are essentially the same: an abomination has occurred in a chamber. The chamber is structure, order, the symbolic; the abomination is reality, disorder; the device is the adaptation of a structure to an abomination that escapes all structure.

.How does this adaptation take place? Through the gaze? Then we're dealing with a stage device. Through the mind? That's what a storytelling device is all about.

What conditions the device

This distinction between means should not, however, give the impression of a free choice given to the artist between different modes of representation. The means of representation are very closely conditioned by history: the history of techniques, inherited cultural models, dominant ones, those in gestation, determine the modalities of the representational device that the novelist, the painter implements, inflects, but does not create, or in any case does not create alone. The device is a meta-level of creation. For example, the generalization of stage devices is linked to the generalization of linear perspective and the hegemonic position of theater among the arts of representation. The development of the storytelling device corresponds with the invention of photography, which makes the darkroom (i.e., the enclosed room) the heart and model of all representational devices. The darkroom is a space of invisibility, radically opposed to the theatrical visibility of the stage.

Forms and contents

However, there is no absolute correlation between these cultural and technological transformations on the one hand, and the nature of the representational devices implemented by an era on the other. The device is only a form, and is based on an extremely long period of culture : different meanings can result in an identical form. The device sediments and fossilizes within itself ancient forms of representation, articulations that are, so to speak, immemorial to culture. The representation screen, for example, transposes the spatial structure of the tabernacle, which conditioned the Christian theology of images throughout the Middle Ages, into the space of scenography. The stage and the tabernacle are the same device, but their cultural content is very different, and in any case unaware of each other. Another example: the current development of virtual representation techniques renders definitively obsolete the scenic devices that entered into crisis with the invention of photography. Narrative devices no longer dialogue with semiotically antagonistic or competing scenes. The space of invisibility becomes the central matrix of filmic narrative: representation thus revives the great narrative cycles of the late Middle Ages, based on the quest, where the object is indefinitely kept out of reach for the gaze. The narrative device is thus Gothic and contemporary. But in one case, it prepares the advent of the perspectival gaze; in the other, it consecrates its end. In one case, it exhausts the resources of the tabernacle; in the other, it prepares the generalization of a thought through images, a non-linguistic, universal, global thought, of which the virtual images, the picture walls of contemporary fantasy constitute only the first imaginary stammerings.

Critique et théorie

Archive mise à jour depuis 2008

Critique et théorie

Généalogie médiévale des dispositifs

Entre économie et mimésis, l’allégorie du tabernacle

Trois gouttes de sang sur la neige

Iconologie de la fable mystique

La polémique comme monde

Construire Sénèque

Sémiologie classique

De la vie à l’instant

D'un long silence… Cicéron dans la querelle française des inversions (1667-1751)

La scène et le spectre

Dispositifs contemporains

Résistances de l’écran : Derrida avec Mallarmé

La Guerre des mondes, la rencontre impossible

Dispositifs de récit dans Angélique de Robbe-Grillet

Disposition des lieux, déconstruction des visibilités

Physique de la fiction

Critique de l’antimodernité

Mad men, Les Noces de Figaro

Le champ littéraire face à la globalisation de la fiction

Théorie des dispositifs

Image et subversion. Introduction

Image et subversion. Chapitre 4. Les choses et les objets

Image et subversion. Chapitre 5. Narration, récit, fiction. Incarnat blanc et noir

Biopolitique et déconstruction

Biographie, biologie, biopolitique

Flan de la théorie, théorie du flan

Surveiller et punir

Image et événement