Acis and Galatea - Poussin

In his preface to Baudelaire's Theater, Roland Barthes defines theatricality as " the theater minus the text "1, that is, as the expansion, the transposition outside theatrical genre of a device and a presence, an intensity proper to the theater.

In classical history painting, theatricality first manifests itself in a very material way through the delineation on the canvas of a properly scenic space, through the isolation of a place where the viewer's eye is supposed to come to focus its attention, through the concentration on a restricted surface of a maximum of meaning.

But there's more : the scene the painter depicts on canvas appears theatrical to the viewer only because it exceeds ordinary decoding, because it adds to what the subject required, because the visual device offers the satisfaction of the gaze an extra presence, a semiotic surplus, an overflow of the rhetorical framework of representation. Theatricality in painting thus presupposes not only the establishment of a fetishistic device on the canvas, but also the overflowing of this device.

Precisely because it defines itself from the outset as an extra-textual constitution of meaning, theatricality accentuates in painting what makes sense outside the relationship, imposed by classicism, of history painting to a source-text enclosing its signified. In this way, it organizes a second structure within the canvas that overflows the symbolic order, making it vacillate and even doubling it. A specifically visual message tends to emerge. The phenomenon of theatricality is thus brought to play a decisive role in the transition that takes place in the eighteenth century from a textual painting, where the subject of history is given to be deciphered and remembered in front of the canvas, which the viewer reads, to a visual painting whose meaning and structure are constructed autonomously in the canvas, according to a logic different from that of the text, delivering to the viewer meaning to look at and no longer to read.

.

Theatricality plays a decisive transitional role in this historical mutation. It appears to painters as a means of formally getting rid of textual painting without abandoning its content. We'll show how, in Poussin's work, theatricality plays the role of a supplement in a space still massively organized around the interplay between signifier and signified and the semiotic bar that articulates and separates them. We will then analyze Greuze's use of Poussin, showing how the advent of total theatricality marks its collapse.

I. Poussin and the logic of the supplement

In a series of paintings from Poussin's youth in Rome, we notice the same device, a curtain isolating a scene within the canvas, dividing the space of representation to result in a compartmentalized structure.

Curtain paintings

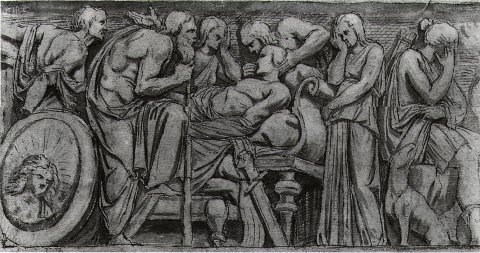

In The Death of Germanicus2, the thick blue curtain thrown behind the dying man's bed circumscribes the site of dramatic crystallization within the interior of a vast stone architecture, the white spot on the dying man's pillow and tunic from which are, will be or have been uttered the words reported by Tacitus3, which constitute the subject of the painting : in essence, that his comrades-in-arms, on the left, avenge Germanicus of Tiberius ; but that his wife, on the right, silently submits to the vicissitudes of fortune.

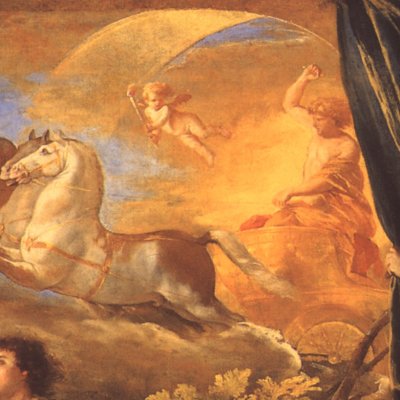

In Acis and Galatea4, the orange-red curtain that protects the two lovers from the jealous curiosity of the amorous Cyclops not only focuses the scene of the theatrical action in the painting, once again strewn with white. It itself plays a dramatic role, as it allows us to simultaneously depict the sadness of Polyphemus, playing a melancholy tune on Pan's flute alone on his rock, and the sensual, dreamy kiss of the nereid and the shepherd, whose greedy consumption is represented by the fleshy thickness of Galatea's lips. Let the putti drop the curtain and the Cyclops' abandonment turns to murderous violence. The theatrical display of the kiss depends solely on the prevention of this gaze; the dramatic suspense merges with the suspense of the curtain.

.

The orange curtain that serves as a canopy for Mars and Venus5 does not, for its part, prevent the nymph and the river god from contemplating the scene. Aided by her putti, the goddess disarms her lover. The cherubs complete the circular, enclosed space outlined by the canopy, trapping Mars in a prison of love where, fascinated by Venus's eyes, he is undone, to the point of losing his sex. No white sheet here, but the whiteness of Venus' body stains and fixes the eye.

In Diane et Endymion6, the blue-green curtain drawn to the right by Night takes on a separating and dramatic function : it isolates the front of the painting, the end of the night that forces Diana to separate from the shepherd Endymion whom she loves and who, angered by her departure, asks her for immortality. The back of the painting depicts the beginning of day, when Apollo, Diana's brother, rides into the sky on the sun's chariot, preceded by the dawn sowing the air with roses and illuminating a sleeping man, god Sleep or Endymion's companion. Even more so than in Acis and Galatea, the curtain fulfills a limiting function here, as it opens, i.e. both abolishes the boundary that allowed the scene and enables its representation. Indeed, Diana can only manifest herself to mortals at night. But the painter needs Apollo's light to produce the image of her nocturnal loves.

Still another of Poussin's early paintings, Céphale et l'Aurore7, also set in the night. The Hours on the left dismount their chariot to come and snatch Aurora from Cephalus' arms as the night draws to a close. The amorous couple, like Acis and Galatea, like Mars and Venus, are protected, surrounded, isolated by a vast orange-beige curtain against which Aurora's white blouse stands out. Two putti watching Cephalus' sullen farewell from above the curtain mark, with their indiscreet glances the boundary they transgress, the /// threshold of the stage they cross.

We could perhaps add a few pure curtained bacchanals to this list. But the device is never as explicit there, and for good reason : the ritual of the banquet is not that of the theater, and the exhibition of a scene has nothing to do with the general overflow of drunkenness. It should be added that after 1630, i.e. even before his trip to Paris (1640-1642), this type of device disappeared from Poussin's paintings. Apart from the material space it delimits, what symbolic function does the curtain play in these paintings? What, beyond the geometrical scene, is the theatricality of these representations ?

We've already noted that the curtain not only designated the stage ; it also had a protective function ; that it sheltered from Polyphemus' gaze in Acis and Galatea, from daylight in Diane and Endymion that it enveloped the amorous couple in its maternal bower in Mars and Venus or in Céphale and Aurore. The canvas thus distinguishes between a protected and an exposed place, a place where exhibition is regulated and a place where it becomes disordered.

The cleaved space of Acis and Galatea

This division is particularly clear in Acis and Galatea where the canvas, cut in two vertically by the two putti in flight and the triton blowing its marine horn, distinguishes on the left a space where the curtain constitutes the semiotic bar, materializes the sign in its internal cut : above, the song of the signifier is blown by Polyphemus below, the title characters of the painting designate its signified. This highly semiotized space on the left is contrasted with the space on the right, an additional, gratuitous bacchanal where desire, which no semiotization orders, is displayed in disorder8 : the blue of the nereid's sheet that a triton hugs under the thighs recalls the one on which the forbidden lovers, so wise in comparison, sit on the left. But he no longer spreads out the space of a scene on the floor; he plays the voluptuous undressed, fetishizing himself as an instrument of desire. The regulated space has become a non-space, shimmering with the shimmering objects of a raw scopic impulse: the abject gray snaking of the dolphins in the foreground, the black shimmer of the surf on the rocks, the flutter of the blue sheet that darkens on the right to the silver-spiked hair of the bearded newt, everything in this tumultuous part of the canvas dissolves the gaze, scatters attention, fascinates and baffles, right down to the goat with its gleaming horns that joins the two incommunicable places, whose obtuse gaze alone transgresses the protection of the curtain. Absurdly lost from Polyphemus's herd on the rocky shores where nothing grows, indiscreet and obtuse, the goat nonetheless represents the spectator through the gaze from outside that it fixes on the stage, whose theatricality it manifests and reveals. The symbolic order represented by the geometrical device of the curtain is thus only achieved through the imaginary detour of the right, whose impulsive power makes up for the gaps in semiotized space, the frustrated desire of the Cyclops, the promised death of Acis and her ultimate metamorphosis into water9. The imaginary outburst of the bacchanal on the right compensates for the symbolic impotence on the left, and this balance is struck at the intersection of all the lines of the composition, at the feet of the goat that has come to bypass the semiotic bar of the curtain, crystallizing and constituting through its break-in the enclosed space of the theatrical stage and the spectator's gaze that only this break-in can realize. What we see of the embrace of Acis and Galatea, no one should see theatrical painting, by exhibiting the signified on the stage of representation, transgresses the symbolic prohibition of the gaze, bypassing the necessary veil that withdraws the face of the goat from view. /// of God and coitus of the Father. But this transgression is incomplete, this circumvention unfinished: in extremis, Galatea adjusts Acis's orange tunic, diverting the gaze from the sex to her pointing finger, substituting for the function of the phallus (the penis is nevertheless visible, albeit in shadow) the monstrous function of the gesture that both designates and covers, guides the gaze and steals the object. What theatricality shows noisily and vividly, this forbidden scene on display before us, thus appears out of step with the painting's primary object: theatricality supplants the function of the phallus, superimposing itself on it and diverting the scopic impulse of sex stretched out towards the pointing finger. Theatricality thus accomplishes the junction between two incompatible symbolic orders: if it bases its device on this order of writing by which painting gives itself to be read in relation to its mythological subject and even more precisely to the text of Ovid from which it draws its inspiration, it is to divert the order of writing into an order of the visual, where the primitive scene played out by myth becomes a scene of effraction and semi-transgression, in a word a scene of exposure.

.

This détournement has nothing to do with a simple transposition of one genre into another, or even of a written medium onto a visual one. What we're talking about here is not the transition from Ovid to Poussin, but the staging, in Poussin's own painting, of a radical change in civilization, a mediological revolution. Everything here is still controlled by the age-old ritual of painting, which is not to be seen in the modern sense of the word, but to be read and decoded in order to reconstruct its history and subject. Yet here, this ritual reaches its limit; it exacerbates the semiotic organization that manifests it on canvas, staging not yet the bankruptcy of the signified, but its vacillation, its splitting, the gap between the sex in the shadow on Galatea's finger. There can be no theatricality without this gap; as the gap widens, the theatrical device collapses.

The function of lack in the semiotic space of Mars and Venus

In Mars and Venus, we notice the same vertical separation between the actual scene on the left and its imaginary supplement on the right. The theatrical pairing of Mars and Venus is matched by the languid postures of a nymph and a river-god spectator. Rather than libidinal outbursts, Poussin has chosen here to evoke a sense of rest after the satisfaction of pleasure, a sort of satiated bacchanal that contrasts with the blazing desire of the divine lovers. The painting focuses the viewer's attention on the gaze they exchange, the bewilderment of Mars' pubis, where Eric Zafran distinguishes under the microscope the subtly indicated virtuality of a penis10 that the common eye is hard-pressed to glimpse. The ravages of time seem hard to invoke when we consider the feminine position of the disarmed Mars, his wide hips, his spread thighs, his beardless and generous chest, the affected movement of his left leg and hand, all of which arouse unease and force the viewer's eye back to the amorous exchange of glances. This vacillation of the signified repeats the theatrical gap in Acis et Galatée and allows the semiotic organization of painting, based on the written word, on the mythological subject, to switch to a symbolic organization based on the visual and driven by the scopic drive.

The curtain here does not play the role of semiotic bar, even if the foliage that overhangs it figures its attenuated device. The compartmentalization of the canvas has been simplified Poussin has somehow concentrated Polyphemus' gaze and the tritons' enjoyment in the same space. The two /// The figures on the right are both spectators and exposed, both prying eyes and satiated bodies. As a result, disorder changes sides: it is the place on stage where Mars is undone that appears as the deregulated space of exhibition, while the two spectators, symmetrically arranged, and the nymph's body reflected in the water offer the gaze a stable, closed structure, a serene supplement where to rest from what in the theatrical play is lacking and worrisome.

Punctum and interlacing gaze in Diane et Endymion

But it is perhaps in Diane et Endymion that Baroque dramaturgy manifests itself in its most dazzling theatricality. Apollo's chariot hurtling from the backstage area, spectacularly opened to view by the drawn curtain, recalls the stage's machineries and the pre-Classical principle of its compartmentalization.

All the subtlety of the composition lies in the confusion of height and depth, made possible by the conventions of Albertian perspective. While the geometrical space is constituted horizontally by a front and back stage, the symbolic space reproduces the vertical division already operative in Acis and Galatea between the luminous epiphany of the signifier above and the suspended vacillation of the signified below, the intense exchange of glances destined to unravel when Apollo arrives. The semiotic bar of the rising curtain is extended by the cloud on which the horses of the carriage gallop. If no bacchanal here overflows or supplants the work of lack indicated by Diana's pointed arrow on the theatrical stage, the overflow is dynamically represented by the triangular composition that joins and articulates Diana to Apollo, the crescent that designates her at her forehead superimposed on the hoof of one of the horses11. Diane transgresses and crosses the semiotic bar; her golden-yellow drapery links her to the superior universe of the signifier, whose uniform she wears. Although there are no fabric throws delimiting the space of the scene, the embankment in the center, the slope behind and perhaps a stream arrest its outline, while Endymion's cane, curving in the foreground, seems to indicate by its shadow that the ground is also curving, as if stopped at the front of the ramp. At the junction of the two spaces, the sleeping man faces us, parodically representing our gaze, like Polyphemus' goat. The two children lying at the feet of the winged Nuit pulling back the curtain are Sleep and Death. Placed in the symmetrical position of the sleeping shepherd, the headless child in the red tunic would rather designate Sleep, while the other, in the foreground, with his shroud sheet, could represent Death.

Curious device this right leg of the dozing toddler that seems to emerge from his left knee articulated to the right foot of Night.... Wouldn't the psychoanalyst's eye see in this the half-chance assembly of a phallus and that play of anamorphosis so characteristic of the screen through which the gaze captures the image12 ? Isn't the trouble that points the viewer in the face of this off-center Death, which another gaze additionally identifies as an incomplete phallus whose missing testicle is provided by Nuit's foot, the same trouble that led him to avoid the feminine posture of Mars ? The visual crystallization that takes place here manifests the ambiguity of the punctum as Barthes defined it in La Chambre claire13 : a totally accidental and subjective configuration, an almost delirious effect of the viewer's fetishism, the punctum legitimizes itself... /// However, it's the fact that it's repeated from work to work, from image to image, arousing the same unease. In Poussin's work, it is the locus of ambiguity and the failure of desire, the counterpoint to theatrical display, what undermines it from the outside : the obtuse gaze of the goat the snide eye of the River resting on the impotence of Mars here, the phallic somnolence of Death in the Skirts of the Night, parodying the articulation of Diana's crescent and the sky through saucy footwork.

The device of the painting is then revealed in its double play of diagonals : from left to right, the descending diagonal opposes two systems of articulation the ascending diagonal contrasts two stagings. Indeed, the crescent on the hunter's forehead, superimposed on the hoof of one of the solar horses, articulates Diana and Apollo at top left, while at bottom right, the same constitutive heterogeneity of the gaze, the assemblage of Death and the phallus, the Lacanian [-f], responds to the same heterogeneity of the gaze. On the other hand, the staging of the signified in the lower left, the farewell of Diana and Endymion, is matched by the entrance of the signifier, the burst of Apollo from behind the curtain in the upper right. The performance space is thus stretched to its four corners, while the center of the canvas vanishes, occupied by five sheep in disarray, emptied. The scenic diagonal constitutes the interplay between signifier and signified; it semiotizes space. The articulatory diagonal, on the other hand, goes beyond this game, while at the same time merging geometrically with the semiotic bar. We've seen how Diana brings the signifier into the signified and how, on the other hand, the sleeping putto between Nuit's feet represents what, in the gaze, is irreducible to the geometrical structure of space it is that anamorphic object that manifests at the front of the canvas the outpouring of the scopic impulse.

The difficulty of interpretation here is that the semiotically ordered theatrical space and the site of visual satisfaction through which the dialectic of lack and supplement is played out, instead of being sharply separated between the right and left of the painting, as in Acis and Galatea or in Mars and Venus, are here intertwined in chiasmus : Poussin is moving towards a new conception of space, no longer compartmentalized in the manner of the Baroque stage, but unified by Albertian perspective, as in Italian theater14.

The screens of The Death of Germanicus

Before turning to the centered paintings and unified perspectival spaces of the aging Poussin, we'd like to return to the painting that is perhaps the starting point for all those we've analyzed so far : The Death of Germanicus, one of Poussin's most famous paintings, is also one of the most distinctly theatrical, because not only is the curtain device present in it, but the very subject as Tacitus tells it constitutes in itself an argument for tragedy. La Mort de Germanicus was, perhaps for this reason, welcomed by its spectators both as an example of virtue and as an example of painting, to be imitated by Greuze, by David, and then outright copied by Géricault and by Gustave Moreau, not to mention the circulation of engravings.

The architectural space in which the scene is depicted already poses a problem : at first glance, we distinguish the left side, where the depth of perspective is marked by the interlocking of three arcades, from the right side, where the eye is arrested not only by the blue curtain, but by the stone wall to which it seems more or less attached. The space would thus be divided, compartmentalized, as in the mythological paintings that we /// the right perspective. However, on closer inspection, the right perspective is blocked only by an artifice of the overall layout, which places the central pillar in front of the right opening of the second and a fortiori third planes. The obstruction is not total: Poussin has, in spite of everything, depicted the nascent arcade in the second plan. The architectural space thus turns out in fact to be a homogeneous space of three times three arcades the depth of the room is the same throughout only the painter's choice of viewing angle masks the depth on the right and gives the impression of an asymmetrical architecture.

As a result, we may well wonder what the curtain is all about, as we notice that it doesn't reach all the way down to the ground in the bottom right-hand corner. The curtain's function as a screen is thus revealed and betrayed: by blocking perspective, by floating insolently in front of the geometrical space, the curtain screens the path of the eye and thus constitutes the field of the gaze, within which the scene can be played out. The curtain crystallizes a stage front, the place where the symbolic message is played out, while reality (raw desire in Acis and Galatea, nature in Mars and Venus, architecture in The Death of Germanicus) is diffracted to the margin, outside. Theatricality isolates itself at the heart of reality : the curtain of the painting is not the curtain of the modern auditorium, which hides the stage ; it is the curtain of the Baroque gaze which, behind, manifests that it is there in front that the theatrical ritual is played out, that it is there that one must look.

Before the curtain, then, is circumscribed the semiotic space where the theatrical scene is played out. In this space, we can distinguish three parts on the left, the tumultuous, motley troop of soldiers overflows the curtain pushed back from the center to the right, dying Germanicus emerges from the sheet and his white garment on the right, Agrippina surrounded by three children and a follower hides her face with her right hand. Agrippina's bust and leg, linked to the leg, breastplate and raised arm of the central soldier, form a V that links the left and right sections, whose bright, saturated colors contrast not only with the white surrounding Germanicus, but also with the painter's work here, whose blurred, indecisive style contrasts with the clean, firm lines of all the other figures. We thus see the emergence of a differential system opposing the signifier, Germanicus pronouncing or having just pronounced Tacitus' words, and the signified, the soldiers and the young woman reacting to these words. Germanicus represents the enunciation; he is the source of the text that structures this painting. Agrippina and her comrades-in-arms represent the enunciation they mime the content of the text, the injunction to some to avenge the betrayed hero, to the other to be forgotten and silently accept the setbacks to his fortune. However, the whole point of the device lies, on the one hand, in this V, which represents the semiotic bar in a broken form, and, on the other, in the overflow of the scene by what precisely constitutes it, the reaction of Germanicus' officers.

As for the screen function constitutive of the gaze, it is redoubled at several points in the painting : the two main characters confronted by Germanicus' words withdraw their eyes from our gaze. Agrippina is hidden by her hand and her handkerchief; the man in the golden breastplate is concealed by his upraised arm, attesting to the gods that he will carry out the vengeance. There's something paradoxical, even irritating and frustrating about these subtracted glances isn't it precisely the reactions to Germanicus' death that the painting set out to show ? Aren't the faces of Agrippina and the man with the oath precisely the signifier of the scene, the means of representing what Germanicus is saying? By masking these two key expressions, Poussin makes it clear that what I want to see in painting, painting never shows me, always forcing me to take an indirect, shifted look15.

Contrary to the actor16, the painter does not exhibit himself before his spectator : it is not monstration, but rather subtraction, thwarting that organizes pictorial theatricality. Through this subtraction, the fundamentally unrepresentable character of the signified is recalled, as in Mars and Venus was elided the penis of the warrior lover, as in Acis and Galatea the nymph's finger baffled the viewer, as in Diane and Endymion the opening of the curtain signified between night and day the pictorial impossibility of representation.

To these two masked gazes, in the center and on the right, let's add those on the left, strangely disquieting : in the background, the man in green closes his eyes, flexes his hip and rests his head on his hands as if, in pain, he's about to fall asleep. In front of him, the man in blue wipes his tears with his hand and turns his back to us. On his head and at his waist, the remains of a lion perhaps evoke the proximity of the Parthians, renowned hunters. But above all, the lion's head, with its mouth covering the soldier's skull, substitutes the devouring gaze of the lion for the gaze we are deprived of. Both the lion's mask and the sleeper's pose disturb what my gaze expects, and fail to expose the painful explosion I've come to seek. The device of the mask and the subtraction of the expected gaze are doubled by the play of reflections: the golden breastplate of the man with the oath reflects the bust of Germanicus, distorting it. Splitting it, it dissolves it into pure shimmer, de-emiotizing it, as if this reduction were necessary to move from the textual to the visual organization of representation.

Finally, let's add to this disappointing series the enigmatic strangeness of Germanicus's eyes : diaphanous, they have the same wax color as his skin. Are they open? Are they closed? The man is as good as dead, and this is indeed a way of excluding himself from representation.

The scopic overflow

Yet this painting is full of glances. Behind Agrippina and behind the man with the oath, they are arranged as if in a case around the V, manifesting the marginal, peripheral constitution of the gaze, around a theatrical scene stricken with blindness. Without dwelling on the gazes of the children and soldiers, let's focus on what's going on underneath and behind the bed.

From under the bed, first, in front of the man in red, between the bangs and the gold tassel of the bed throw, we can make out Germanicus' arms, his circular shield on which his sword is resting, protruding to the left, and his helmet, of which only the part protecting the neck is visible. Now, what do we see on this helmet pointing out from under the bed ? an eye. Is it the reflection ? Is it the design? In any case, this eye looking down at us transgresses the sort of secondary screen formed by the yellow bedspread.

More insistent and more indiscreet is the transgression played out above, in the blue curtain. A man is watching. Is he there to hold the cloth? Is he a spy for Piso, Germanicus' enemy, whom Germanicus suspects and accuses of poisoning him, with or without Tiberius' consent? What's worrying about this figure is a kind of soft stretching of the character, as in that part of the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel where Saint Bartholomew brandishes the skin of his martyrdom, to which Michelangelo has given, in anamorphosis, the shape of a self-portrait. Here, the hollow of the neck, plunged into shadow, abolishes all contours.

To the geometrical overflow of the scene by Germanicus' overly numerous troop of officers is thus added a scopic overflow, through a disquieting and unexpected double gaze : first it's this ocelli eye17 of the golden helmet under the bed, a meaningless eye where /// my gaze is annihilated. Then there's the spying eye of the shapeless shadow with its arm raised in the curtain, signifying the forbidden gaze with which the signified is always struck. Right next to the shadow, the sword brandished vertically by the soldier with the silver helmet and the four-medallion sign recall, by contrast, the symbolic effectiveness of the scene, the power of Germanicus and the imminence of vengeance, as if the place of the rift and abject emergence, the place of scopic transgression were to coincide with that of the symbolic, f and [-f] side by side, right side and wrong side of the same function18.

Modeling the theatrical device

The constitution of the theatrical device in painting can thus be summed up as the establishment of a system of screens at three levels : at the geometrical level, the angle chosen by the painter and then the curtain placed behind the stage screen the eye's forward run towards the perspectival vanishing point, stop and fix the gaze, construct the space of representation.

At the level of representation, the hidden gazes of Agrippina and the man with the oath, the blurred facture of Germanicus' face screen the monstration of the signified, confuse the spectator from direct access to meaning and strike the theatrical scene with blindness. A ban on seeing is established. The eye then enters the scopic game, which overflows the semiotic constitution of space.

At the scopic level, finally, the transgressive gazes of the man in the curtain and the ocelli on the golden helmet represent the transgression of the prohibition of representation. These gazes are worrying: they are not content with seeing as we see what it is forbidden to look at they represent the neantization of the subject, the reduction to zero of the spectator looking. The empty eye of the helmet and the limp figure with the raised arm of the curtain are signs of death, zero-symbols of the fact that, in front of the painting, I am led to forfeit, to lay down my gaze19 : grimacing masks, they defuse the impulse.

These last two levels turn out to be completely intertwined : do the lion-skinned man and his seemingly sleeping companion, by removing their gaze from ours, screen the monstration or are they figures of the scopic drive where the subject both forces the forbidden gaze (through the lion's head) and annihilates himself (sleep and devouring are signs of death).

But what interests us here is the repetition of a single mechanism by which theatricality is constituted, the mechanism of the screen that baffles the eye and reveals the scene, of the blindness that illuminates, of the neantization that opens to the satisfaction of the drive. Not only does theatricality require a series of screens to reveal itself, but it always manifests itself in the overflow of these screens. The soldiers overflow the curtain; the pain overflows the hidden faces; the spy and the golden helmet overflow the forbidden gaze. Theatricality in painting is indeed a production of meaning, a symbolic production. But since the crystallizing phenomenon here is that of overflow, this symbolic advent is not the result of the cut and alienation inherent in the semiotic constitution of space. Another symbolic, a visual symbolic, is put in place.

We've seen how, in mythological paintings, the signified wavers. We noticed, in The Death of Germanicus, the indecisive making, the vacillating blur of the bust of Germanicus. There can be no theatricality without this vacillation, without this figuration of a failure of the signified through which the dialectic of lack and supplement is set up. We must be wary, however, of reducing the structural analysis of theatricality in painting, and the deconstructive dialectic that underlies it, to a pure game. /// of masking and unmasking, annihilation and overflow. This game is motivated by an ideological stake that overhangs it: through theatricality, it is the symbolic order itself that is put into play, displaced, reshaped.

Alexander's mirror and Meleager's ghost : Germanicus palimpsest

In effect, let's take up the analysis of the painting no longer by following the interlacing of the gaze in which it traps us, but by focusing on the meaning of its representation, on what motivates the subject, on what originally works in the device.

Tacitus remarks in the Annals that some people, at the time of Germanicus's funeral, " compared his beauty, his youth, his death, even because of the proximity of the place, to the fate of Alexander the Great "20. Yet, as Alain Mérot notes, the motif of the young hero's glorious death carried by history is here reversed : " the hero is here shown unjustly persecuted rather than clothed in the glory of the world "21. Germanicus is an anti-Alexander despite the formal similarities: while both men die in the same East, of the same fever, with the same suspicion of poisoning22, Alexander is the conquering king, Germanicus is the victim and betrayer. Alexander's gesture is epic; Germanicus' fate is reminiscent of tragedy. Poussin's purpose in composing this painting thus appears the reverse of that which Le Brun would have for the Versailles series of the Battles of Alexander : not yet to found absolute monarchy, but already, ten years before Le Cid, to signify the end of the feudal aristocratic ideal.

Or, to arrange his figures in antique style, Poussin would have been inspired by an antique sarcophagus, on which, in bas-relief, was carved the story of Meleager. The frieze links three scenes: in the first, Meleager daggers Calydon's boar, which Atalanta has wounded with her javelin. We know that afterwards Meleager killed his maternal uncles because they didn't approve of the gift he made of the beast's remains to Atalanta23. The second scene shows Meleager's mother, incensed by her son's murder of her brothers, throwing into the fire the magic firebrand which the Fates had foretold Meleager would die from when it had finished burning24. The third scene depicts Meleager on his deathbed25. We recognize the weapons under the bed, the companions at the bedside and the upturned figure of Atalanta the huntress, accompanied by her dog and holding her head in her hands. This is indeed the embryo of the stage set-up for La Mort de Germanicus.

But there's more : the filiation of Méléagre to Germanicus is full of meaning. The entire legend of Meleager is bathed in the aura of Artemis. It is Artemis who sends a devastating boar to Calydon as punishment for a neglected sacrifice26 Artemis protects Atalanta, virgin huntress /// like his protector27. On the other hand, Meleager appears in a system of matrilineal filiation: if his father is uncertain (is it Œnée, the king of Calydon, or Arès ?), it is his mother who disposes of his life through the intermediary of the firebrand, and it is the authority of the maternal uncles, not the father, that he must transgress. Finally, the whole story is based on a game of balance between Atalante and Meleagre, a conflict between two symbolic systems : the artemisian ritual of the hunt is opposed by the qualifying test of the warrior hero.

On the sarcophagus, Atalanta, standing and turned around, seems remorseful that Meleager dies partly because of her. However, the two figures, who turn their backs to each other, contribute to the same symbolic elaboration: the death of one is the punishment of an outraged mother; the sadness of the other isolates her in her fierce virginity. In both cases, archaic femininity is at work, whether in the form of the vengeful Althea throwing the transitional object into the fire, or in that of Atalanta, frozen, inverted, blinded, constituting herself entirely as a pre-object phallus. Agrippina condenses the maternal violence of Altheus and the virginal imprisonment of Atalanta: her husband's last words are to suppress his fury; in the foreground of Poussin's painting, surrounded by her children, she occupies a place as massive as the huntress of myth, compared to whom Germanicus seems crushed. Beyond the formal device borrowed from the sarcophagus, Poussin's depiction of Agrippina as Atalanta/Althea is the instrument of a truly iconic constitution of the scene: if the semiotic bar and the law of the father regulate the textual organization of meaning (Germanicus' speech and the V on the canvas), it is the composite assemblage of mother and pre-object that organizes the image, for this assemblage is nothing other than the symbolic function at work in the screen device. The mother acts as a screen, her body interposing itself, preventing the gaze and at the same time satisfying my impulse; the objet petit a, for its part, is the screen it represents the " moi " neantised on the canvas. Agrippina damaged by pain and the spy with her arm stretched out in the blue curtain thus answer each other on either side of the bed, terrible mother and consumed firebrand, massive body and projected phallus.

Are the lion's remains on the left figure not a nod to Calydon's boar, whose remains were so coveted ? This would be a sign that, in Meleager's sarcophagus, Poussin has not merely taken a convenient arrangement of figures and objects, but rather a device where a certain symbolic operation was at work that is found in The Death of Germanicus. Let's go further : the dialectic of the supplement that led us to consider the operation of theatricality in Poussin's painting in terms of the overflow of the semiotic system seems to manifest, in a general way, nothing other than the maternal overflow in which the pre-œdipian subject is neantized. What's unexpected about such a device is that it produces the symbolic outside of alienation, outside of the cut.

When shadow screens : paintings of maturity

But it's in Poussin's mature works that this alternative structuring of the theatrical symbolic manifests itself most vividly. We'll stop at La Mort de Saphire28 and the Christ and the Adulteress29, because they are elaborate /// using a virtually identical device. There's no curtain here to justify comparing the painting with a theater stage. What's more, the composition, rigorously centered on a frontal architectural perspective, abandons all reference to Baroque compartmentalized stages. It has to be said that the dramaturgy has changed, and that Italian-style theater, based on the spectator's frontal gaze and focused on a single center of interest, has become the norm. But above all, St. Peter's pointing finger in The Death of Saphire, and Christ's in the second painting, make the expressive, demonstrative gesture the fundamental spring of theatricality in these paintings, whereas this type of visual effectiveness was systematically avoided in the curtained scenes of 1628-1632. Something therefore shifted, a balance broke after 1650, leading to unease and criticism among Poussin's contemporaries, whereas La Mort de Germanicus had aroused enthusiasm. We will endeavor to show how theatricality, by becoming autonomous in these paintings, endangers the very principle of representation.

The screen device, despite the absence of a curtain, is preserved in these two paintings. The second plane is plunged into shadow, isolating the luminous foreground scene from the architectural background, also bathed in light, by an opaque space. The eye's forward flight into the geometrical background of the painting encounters this shadow, which stops it and allows it, in front of it, to constitute a field of gaze. The device is timid in La Mort de Saphire Poussin has reinforced the effect of the shadow with a parapet that he has placed behind Peter, who is accusing, Paul, who is raising his arms to heaven, and the third apostle in the red cloak. The parapet again recalls Germanicus' curtain. It disappears in Le Christ et la femme adulère, where the shadow alone acts as a screen30.

The paving on the floor, characterized by a homogenous, blended color scheme in La Mort de Germanicus, is here sharply contrasted, suggesting a checkerboard pattern. Poussin thus marks, or betrays, his use of the perspective box, where the figurines laid out on a checkerboard by the painter enabled him to draw the main lines of his composition, by applying an eye in the hole provided on the side of the box31. Poussin therefore staged his figures before painting them, arranging them in his box as he would have arranged actors in the theater. This perhaps explains the much more theatrical poses, the gestures that are both stylized and exaggerated, and right down to the fixity of the eyes, so characteristic of Poussin.

Charity in question in La Mort de Saphire

In La Mort de Saphire, the checkerboard and architecture seem to semiotize the entire space, and leave no room for any place of overflow and indifferentiation. Let's recall the facts that motivate the painting in the early Church, the custom was established among the faithful to sell all their possessions to pool them according to each person's needs32. Now Ananie and his wife Saphire, when they sold their property, secretly reserved part of the proceeds for themselves. Ananias lays the money at the apostles' feet. Peter accuses him. He falls over dead. Sapphira arrives three hours later and appears before Peter. This is the moment chosen by the painter " Peter said to her : Why did you agree to test the Spirit of the Lord ? See the feet of those who buried your husband, at the gate, and who are going to take you away too33. She fell immediately to her feet and expired. The young men returning found her dead and took her away to bury her beside her husband34. "

According to the biblical text, we can distinguish on the canvas, clearly separated by the void of the two steps in the center, the signifier on the right, the group surrounding Peter who pronounces the fatal words, and the signified in the group on the left which figures the content of these words through the green complexion of the dying Sapphira, through the sorrowful expression of the three women in her retinue, through the look of obedience cast on the apostle by the two men already turned to leave carrying the corpse. We can even note the orientation of Saphire's downcast gaze, towards the foot of the man in yellow, in keeping with Peter's words, Ecce pedes.

Thus, diagonally, the semiotic bar that structures the space takes shape: it starts from Paul's raised hand testifying to God at top right it runs along the fold of Peter's yellow toga, arm and pointing finger it reaches the head of the next woman in white, whose gaze on Saphire relays that of the apostles it follows the next woman's arms to Saphire's eyes and, from there, slides down her red sleeve to the gravedigger's foot.

Highlighting this line reveals the deeper meaning of the pointing finger. Contrary to what we might expect, its function is not to show, to exhibit, to make the object of the painting visible. A signified cannot be designated; it must be delimited. The pointing finger does not lead the viewer's gaze towards the object of his satisfaction, since its ultimate target is not Sapphira but the gravedigger's foot, its true origin, not Peter's gaze but the invisible gaze of God to which Paul's two raised arms refer. By annihilating Sapphira with God's own hand, the performative gesture (and not the monstrative one) represents the efficacy of the signifier; it is what, in painting, traces the textual meaning of the representation. It's an arm that must be traced, not followed, to find out who's speaking and where the signifier lies. Pierre doesn't point at Saphire. There's no accusation to be made, because the matter has already been judged. Theatricality here presupposes a transcendence, an invisible and sovereign eye from behind, to which there is nothing left to show that it has not already seen. And yet, on closer inspection, the semiotic economy of painting is not as well regulated and locked down as it might seem. First of all, the group of figures that constitutes the signified is in the process of unravelling. Poussin has artificially combined two distinct moments: Saphire's fall among her wives, and the arrival of the two men to take her away. In the movements of the figures, we can distinguish two intersecting curves, both starting from Saphire. One passes through the woman in white kneeling on her right, rises towards the woman in blue whose arms indicate that she still wants to stay, then moves away towards the woman in pink who urges her to leave with her right hand and, bringing her child back onto her left hip, turns him away from the show. The other curve follows the opposite path: it passes by the man in yellow, whose ambiguous gesture hesitates between supporting the dying woman's arm and abducting her, and, following the shape of her body, rises to the right, following his left hand which, pushing aside the woman in blue, calls for help from the man in pink, whose hands already indicate that he is about to leave. The colors themselves suggest symmetry : the man in pink, whose undergarment is green, is answered by the woman in pink, whose skirt is green the man in yellow, whose undergarment is blue, is answered by the woman in blue, whose tunic is yellow.

The signified thus splits and unravels into two diverging curves (one to the left, the other to the background), which at their intersection provide an empty center, where the gaze will lose itself in the shadow of the /// background. The red stain on Saphire's tunic and the very title of the painting should focus the eye on her expiring body. But Pierre's words, the uncertainty and then the flight of the figures around him prevent this focus. The two men look at Pierre. The woman in pink looks at the woman in blue, whose gaze is prevented by the interposition of the man in yellow. Saphire is only looked at on the line of the semiotic bar, by the apostles and by the woman in white. But this line, as we've seen, is nothing more than a trap for the gaze, an illusion of gaze in which to trap and neanitize the viewer. Saphire is thus forbidden to be seen falsely exposed, through the dynamic play of the pictorial device, she is in fact subtracted even slouched on the foreground, the signified remains invisible. Torn between the hands of the next woman in white, who tries to lift her to the right, and the man in yellow, who is already carrying her to the left, Saphire herself unravels. The dark color of the clasp, the lace of her bodice and her belt, merging with that of the skin in the shadow of her head, seems to have already divided the red mass into three pieces to be detached.

The peril and destructive suspense in which the theatrical scene stands do not in themselves alter the devices at work in the curtain paintings : the curtain drawn in Diane et Endymion heralded the fading of the signified with the arrival of light ; the curtain in Acis et Galatée, by revealing behind it the gaze of the Cyclops, prepared the ruin of the amorous union being played out before us. The theatricality of the painting lies in this imminence of destruction, in the instability of the equilibrium on which the stage is built. What's new here is that on the stage, the division has already been made, the body already broken, the void already installed, as if the painter had pushed the moment of representation a little too far back in time, as if the painting had slipped beyond its moment of equilibrium. The rupture has moved from the frame to the heart of the installation. It's no longer a curtain being drawn to expose an idyll to the destruction of a gaze it's a tunic being torn over a body in agony.

The link between theatricality and death is thus accentuated, leading the semiotic bar that runs through the painting to play the role of neantizing anamorphosis where [-f] comes to work: like the foot of Nuit and the legs of La Mort in Diane et Endymion, Paul's two hands and outstretched finger here take the place of phallus, and of a phallus whose erection gives death. Peter's gesture not only fails to show, but above all acts as a screen here, neantizing the viewer's gaze, barring access to what, in this painting is really given to see, at the bottom, the gesture of charity of the man in blue who reaches out to a beggar woman sitting by the water with a child.

For there is a second signified : to the play from the right to the left of the painting that opposed the mortifying signifier figured by Peter to the morbid signified personified by Sapphira comes a play between the front and the back of the canvas, the exemplum in the foreground, finding its allegorical meaning in what is represented in the background, the gesture of charity. Sapphire's death is to be interpreted as the punishment for a failure in one of the theological virtues: the lack represented in the foreground is made up for by the gesture in the background. The logic of the supplement is thus reconstituted.

However, the dialectical interplay that is then established between the scene of punishment and the backstage where the virtue scorned in the foreground is re-established has nothing to do with earlier systems that opposed a semiotized space to a space of overflow, bacchanalia or de-emiotization. This time, the supplement is not only ordered, but also delivers the symbolic message on its own. The supplement /// becomes autonomous.

More seriously still, the unease that emerges from the foreground scene calls into question the very homogeneity of symbolic law : is it indeed the same law, the same commandment, that makes the rich give alms who will remain rich to the poor who will remain poor, and that makes Ananias and Sapphira chastise themselves for not having totally stripped themselves of their wealth, to the point of total poverty ? Is this the same law that orders primitive communism in the young Church, and that takes a little wealth for the poor in the institutionalized Church ? Saphire and Ananie kept only a little money for themselves the man in blue delivering his alms in the background parted with only a little money. He makes far less than the woman who dies in the foreground for not making enough.

This critical dimension of representation calls into question the canonical allegorical reading of this episode. To justify it, we could draw on the authority of Voltaire, who in the Dictionnaire philosophique makes the story of Saphire and Ananie a scandalous example of the tyranny of the Church and the violation of property rights. But a hundred years earlier, isn't this kind of criticism anachronistic ?

In these terms, it probably is. The signified is not destroyed ; it is duplicated ; it needs a crutch. Just compare Poussin's composition with that of his model, Raphael's La Mort d'Ananie the central position of Peter, accompanied by the full apostles, has been abandoned in favor of an off-center, isolated position. As for the distribution of the money to the poor, in Raphael it is done by the apostles themselves, immediately justifying the donations of the faithful. In Poussin's work, the two scenes of punishment and almsgiving are completely dissociated. Finally, Ananias' death is the first of the two, the more legitimate of the two. Sapphira's, coming second, may seem superfluous and be understood as an excess of severity.

This is the measure of the transition from the spectacular composition intended by Raphael to the theatrical scene imagined by Poussin : the spectacle, based on monstration, relies on an immediate and unambiguous signified everything is tended towards the object given to be seen the theatricality on the contrary, with its systems of screens, relies on a fragile signified it fills in the cracks, makes up for the gaps, and even here cancels out in extremis the doubling : what links the background scene to the foreground one is the identity of the postures, the same gesture of giving alms and designating Sapphira to divine vindictiveness, the same position on the ground of the humble woman and the liar. Simply, the gesture is reversed: not only in meaning, the negative act in the foreground is reversed into a positive act in the background ; but also in disposition, Peter is on the right, the giver on the left, Saphire is on the left, the poor woman is on the right.

The full extent of the symbolic doubling that goes on in this painting lies in this inversion, and more generally in the visual chiasmus that orders the composition (the two intersecting curves that make up the group of figures surrounding Saphire also form a chiasmus) : by depicting in addition to the scene he was painting the allegorical meaning that should or could have been given to it, as if this meaning ceased to be obvious and transparent, Poussin set it at a distance, played it out, released between literal action and its moral reinterpretation, between the communism of the early Church and institutional Christian charity a symbolic disturbance, an interrogation35.

The negation of the evangelical message in Christ and the adulterous woman

In Christ and the Adulteress, the symbolic doubling is even more blatant. Here, Poussin draws inspiration from an episode in John's Gospel (VIII, 2-11). /// Jesus was teaching in the temple. The Pharisees brought him a woman caught in the act of adultery: according to the Law of Moses, she was to be stoned to death. "Jesus bent down and wrote on the ground with his finger. When they persisted in questioning him, he straightened up and said to them, 'Let him who is without sin among you cast the first stone'" (v. 6-7). As Christ returns to his scriptures, the crowd gradually disperses. When they are alone, Jesus stands up and asks the adulteress if no one has condemned her. On her negative answer, he lets her go.

Poussin set the scene on a paved esplanade. Writing on the ground, a veritable commonplace of ancient philosophical practice, here becomes a miraculous inscription on the paving. Yet, as if the painter wished to preserve a trace of the text's initial situation, a few clods of earth can be seen between Christ's feet and the knees of the adulteress. The first staircase, which sinks into the background, and the second, which cuts across the entire architecture, are also reminiscent of the elevation of the temple, a veritable citadel within the city. In front, on the right, onlookers who have stopped to listen to Jesus' teaching read what the master has written on the floor. On the left, the Pharisees who have come to disrupt the lesson form a tumultuous and disorderly group: their frieze-like arrangement contrasts with the circular movement of the group on the right. Behind, in the shadows, a mysterious woman observes the scene, a child in her arms.

The device is much more complex here than in La Mort de Saphire. Poussin condenses two scenes articulated by the figure of Christ, on the right the reading scene, on the left the accusation scene. The result is an organization of space comparable to that of The Death of Germanicus, where the signified is distributed on either side of the signifier. Germanicus held two speeches, one for his comrades-in-arms, the other for his wife Christ delivers an oral word to the Pharisees, a written word to the disciples. The symmetry of the composition36 here plays on the ambiguity of the gospel text : we don't know what Christ is writing we don't know if it overlaps with what he says about the adulterous woman, if it continues the lesson begun or if on the pavement is written the very text we read in John's Gospel.

What is certain is that the symbolic law is represented on this canvas in several ways that do not overlap : between the theatrical staging of what Christ utters and the textual space in which he literally inscribes himself (he places his foot on his saucy text37) there is already a schize, a vacillation from the authority of Scripture to the authority of representation. But on closer inspection, Christ does not occupy the center of the canvas. The adulteress is caught between two pointing fingers, the protective one of Jesus, who seems to want to lift her up, and that of the Pharisee in the foreground in yellow, whose left hand attests to the Law of Moses (his finger points to the sky), but attests to a law that is now outdated (the finger points into the shadows). As in La Mort de Saphire, these gestures are not monstrative, but performative they give nothing to see they convey transcendence and designate the divine origin of the signified.

Until then, the splitting is programmed by the evangelical text. Poussin goes further. By placing a figure of blissful maternity between Christ and the adulteress from behind, he not only introduces a spy eye /// in the curtain of shadows, a gaze in which the spectator's own gaze would be represented, that is, both unmasked as transgressive and negated as mortifying. He opposes the misuse of femininity brought down before us in the figure of the adulteress with a good use that condemns shameful fornication in the name of legitimate procreation. The eye of the figure in the shadows neantizes precisely in that, from the wings, it carries condemnation of her who, on the theatrical stage, is collapsed.

This brings to mind the mechanism which, in La Mort de Saphire, opposed the theatrical representation of the exemplum in the foreground to the figurative representation of its allegorical meaning in the background. But in Christ and the Adulteress, the figure of motherhood can't allegorize the scene: caught up in the play of the scopic drive and making the Lacanian [-f] work, it remains irreducibly transgressive. And above all, in the end, she signifies the opposite of the Gospel message: where Jesus refused condemnation ("Neither do I condemn you ", v.11), by her mere presence in the shadows, by the child she carries, she accuses. This is where the symbolic doubling comes to fruition, pitting the law of the Gospel against the law of society, which will have the last word. The ideological edifice is cracking. As if to testify to this, Poussin depicts incomplete architecture in the right foreground, an assembly of stones in unstable equilibrium, consolidated and propped up by a beam and a wooden wedge. Such is the fate of the supplement to never sufficiently supplement.

II. Greuze and the logic of effusion

When we move from Poussin to Greuze, we are immediately struck by the disappearance of the vanishing point, by the closure of space, by the disappearance of a geometric beyond to the scene. This closure is not achieved all at once. In L'Accordée de village38, Greuze retained the principle of a screen indicating the location of the theatrical stage in front of him. But this screen has been multiplied and accessorized: there's the staircase at far left, suggesting an escape beyond the brightly lit wall against which the stage is set. But the shadow creeping up the steps behind the supporting pillar is a shadow without eyes, a mere speck that has almost nothing human about it, a pure accident of reddish-brown color on the too-smooth surface of the background. The kitchen door, behind the two maids, is closed, suggesting an escape it does not exploit. The bread bin, above the father and fiancé of the tuned woman, has a piece of white cloth hanging from it, though not enough for a curtain. Finally, on the right, the dresser opens a large door, which again allows no escape. All these elements are virtual indications of a geometrical depth that never comes. The space of the stage is no longer circumscribed within a larger natural or architectural space. The stage now occupies the entire performance space.

However, another delimitation appears, within the scene itself. In fact, despite the illusion of a composition in which the heads seem to form a single undulating line defining a homogeneous plane, all the characters are distributed according to a whole range of interior furnishings. On the right, the tabellion39 who has come to draw up the marriage contract stands behind a table that separates him from the father of the family. The eldest daughter, next to him, is leaning against the father's armchair, the back of which also separates her. On the left, the mother's armchair plays the same separating role for the little girl feeding the chickens. /// and the kid who, leaning on the wooden uprights, rises on tiptoe to see. As for the younger sister, it's the shoulder of the bride she's leaning on that serves as a separation. A semicircle then takes shape, within which the mother, the bride, the young man and the father of the family, with their intertwined hands and arms, stand out as the protagonists of the drama. The others are spectators, watching from behind this invisible line where the fetishistic diposition of theatricality crystallizes. Greuze's composition has nothing to do with the transgression by an external gaze of a scene forbidden to the gaze that structured Poussin's painting. The overhanging gaze of the jealous eldest daughter on the right, or of the curious boy behind his mother on the left, are not foreign to the scene. They do not transgress any prohibitions. By circumscribing a space of theatricality within the stage, it is they who assume the screen's true delimiting and crystallizing function.

This change of device, marked by an enlargement of the stage to the entire canvas and a restriction of theatricality to the part of the stage where the hands intertwine and stretch, can be likened to a phenomenon that poisoned French theatrical life during the eighteenth century. To make each performance as profitable as possible, the Comédie française installed a row of chairs for spectators around the perimeter of the stage40. The separation of theatrical play and the transgressive gaze it was supposed to elicit and pretend to ignore was no longer effective, with the stage offering a spectacle where star actors and fashionable spectators were mingled in the same performance.

We'll contrast the theatrical effusion, the overflow of affect emanating from the four protagonists (mother, daughter, son-in-law, father) with the spectatorial dissatisfaction, the lack that works on the other members of the family : the boy on the left lacks the height to see, his younger sister misses the fiancée and can't bring herself to part with her, the jealous older sister feels that her prerogatives as the eldest have been breached as for the tabellion, who is already holding out the notarial deed, he awaits a reward that for the moment he lacks the father gives the dowry, the son-in-law is fulfilled the notary's time comes only later. A dialectical tension is thus reconstituted between a function of lack in which the scopic [-dialectic is thus reconstituted between a function of lack in which the scopic [-f] is at work, and a space of effusion and overflow where the drive is satisfied, the lack, if not filled, at least pacified. The protagonists show their spectators money in the case of the tabellion, marriage in the case of the eldest daughter, emotion in the case of the younger sister, and spectacle in the case of the young boy. But what is given to see is not exactly what was missing it's neither the right money, nor the right marriage, nor the right affect, nor even the right show. Indeed, the show for the children is not that of the dowry gift, but that of the hen and chicks that the little girl, on the left, feeds.

.

If the dialectic of the supplement is still at work here, its terms are thus reversed : with Poussin, the space of the stage was the space of lack that overflowed, out of the limelight, the space of the bacchanal, of Germanicus' troop of soldiers, or the shadow-worked background of La Mort de Saphire or Christ et la femme adulère. Here, the lack is around, the overflow, in the center. The place of theatricality is that of excess, which fills the expectation of peripheral eyes. The device of modern theatricality is constituted here, through the radical reversal of classical theatricality.

We have seen the geometrical origin of this reversal : the expansion of the stage to the entire canvas results in an expansive representation. Space, and therefore hearts, expand. Conversely, the appearance /// of a non-theatrical edge in the scene creates, at this point, a gap. The theatrical stage comes undone, and with it, the gaze.

The new device is also motivated by a symbolic revolution. Indeed, Poussin's painting, as a history painting, was always based on a text. Greuze's genre painting, on the other hand, depicts unwritten social rituals. Admittedly, this a priori opposition is not historical but generic. Greuze follows in the Dutch tradition of Teniers and Wouwermans41. And yet, from this commoner genre, whose material is humble reality, he claims to rival noble painting, to which mythological and historical culture lends meaning and aura. The whole drama of Greuze's career lies in this attempt and its failure. It's Poussin he's confronting (he says so, and the borrowings, as we shall see, prove it), not Dutch interiors. The generic opposition thus reflects a symbolic conflict and reveals a mediological issue.

The symbolic content of history painting was programmed by the source text. Ideally, the pictorial representation isolated from a large text the phrase, the historical word which, in the original narrative, was likely to condense a maximum of meaning, to take the place of an exemplary moral sentence. Through painting, the narrative took on the value of exemplum. Greuze seeks to perpetuate the symbolic efficacy of this historical word in a painting without textual support. What does the father do? He speaks. What does he say? We don't know we have no text to refer to. How do we compensate for this original deficiency ? By adding more to the painting and these are gestures, poses, demonstrations, protests... the time has come for monstration as an effusive supplement to the textual void. Diderot's commentary is significant in this respect:

" Arms outstretched toward his son-in-law, he speaks to him with a heartfelt effusion that enchants. He seems to be saying : Jeannette is gentle and wise ; she will make you happy ; think of making her happy... or something else about the importance of the duties of marriage... What he says is surely touching and honest. One of his hands that we see outside is tanned and brown, the other that we see inside, is white : this is in nature42. "

The whole painting is geared towards what the father of the family is saying. But at the moment of saying it, the critic hesitates and pulls himself together. First, he models : the father " seems to be telling him ". Then he proposes a second, vaguer hypothesis: " or something else ". In fact, the only thing that is certain (" What he says is surely... ") is the effect produced by the words. But the words themselves escape us. On the other hand, Diderot insists on framing his hypotheses by mentioning all the theatrical devices at work in this painting : first, " the outstretched arms " of the father, a monstrative gesture par excellence that reveals the daughter to be married then comes " the outpouring of heart ", characteristic of the emotional expansion through which the theatrical overflow manifests itself then, in conclusion, Diderot describes in detail the father's hands, an instrument of monstration whose color alone delivers the ideological ambivalence of the Greuzian project : le hâle est d'un paysan, la blancheur est d'un maître.

The father's outstretched hand, the gesture's monstrative expansion makes up for the lack of text. Here, theatricality takes the place of discourse. But this substitution is only ideal, as the textual and iconic supports do not overlap. This theatrical supplement is therefore always insufficient : ultimately, the more theatrical the characters, the more manifest the textual deficiency.

The imbalance is particularly noticeable in the Septime Severus and Caracalla43 that Greuze presented in 1769 as a reception piece to be approved as a history painter by the Académie. In the geometrical organization of space, we find the same characteristics as in L'Accordée de village : despite the presence of a curtain and even a dais to delimit a scenic space in the canvas, the absence of depth is even more flagrant than in the peasant interior, with its door and staircase. Here, the wall occupies the entire canvas, and the Ionic pilasters, far from giving it relief, accentuate the impression of crushing perspective and enclosure. Diderot bitterly criticizes the painter for this:

" The background of the painting touches the curtain of Severus' bed, the curtain touches the figures, all this has no depth, no magic44. "

If, like the philosopher, the effect is missed, the process is too systematic not to be deliberate Greuze's aim is to transpose the geometrical screen into a scopic screen, to replace the partial arrest of the gaze in its flight towards the perspectival background of the painting with a scenic border of prevented glances, but integrated into the space of representation. Here, the gazes of Caracalla, Papinian and the young senator are forbidden: on the left, the unnatural son looks away to avoid his father; on the right, the august old man bows his head in dismay; at his side, behind him, the senator freezes in astonishment. These three forbidden gazes delimit the place of theatricality, the bed, within the stage, materialized by the dais.

Greuze drew inspiration for the composition of the characters around the bed from La Mort de Germanicus. The scene, in fact, is articulated, as in Poussin, by the two tenses of the man's speech on his bed : Germanicus formulated an injunction for his men on the left of the painting, another for his wife on the right. Similarly, Severus addresses his reproaches to Caracalla, on the left, then offers him death at the hands of Papinian, on the right of the canvas.

If we follow the logic of the genre rather than that of history, we can claim for this canvas the textual support of history paintings : Greuze went looking for Severus' words in the narrative of Dion Cassius. Yet the immediate legibility of Poussin's painting is contrasted with the obscurity of Greuze's. This time, there's no play of signifiers. This time, there is no interplay of signifier and signified in the pictorial message: the figures do not represent the emperor's words; rather, they elliptically react to them. The painter didn't even hope to be read, since in the title of his composition he includes the text to be substituted. In fact, the Salon booklet bears the following title: " The emperor Severus reproaches his son Caracalla for having wanted to assassinate him in the defiles of Scotland, and tells him : If you wish my death, order Papinien to give it to me with this sword. " What counts in Greuze's work, then, is not what the signifier utters, but the effusive overflow of proferation: between Severus and Caracalla, there is no obstacle, no bar that manifests the semiotic structuring of space, but a strange void, a real hole in the composition, tragically manifesting the textual emptiness that the monstrative emphasis of the emperor's gesture vainly attempts to compensate for. Decidedly, transposition /// from textual to visual, monstrative and theatrical efficacy of painting is not a question of genre, but the result of a historical mediological mutation.

In fact, the blurred, flaky context of the dying Germanicus, whose left hand merged with the color of the bed and right arm folded over his own chest, is opposed by the veritable monstrative explosion of Septimius Severus, the epiphanic figure of the father and majestic Stoic sage (Greuze was inspired by a statue of a Roman fisherman, long identified with Seneca). Here, the painter brings the theatrical effect to a climax by holding out both of Severus' hands, giving us a double view. First, the right hand, extended towards Caracalla, seems to be asking him to come back to him. The left hand, extended towards the sword on the tripod table, indicates the instrument of death. It is not Severus' words that govern the figuration of the figures, but his gestures. Speech no longer structures the performance; it is its overabundant effect: the presence of speech is the mark of theatricality, the result of monstrative expansion. What comes first is the outstretched hand.

Technically, then, Greuze here takes the theatrical device to the height of its effectiveness. Why, then, is the effect missed? Because mediological transposition has profound symbolic implications, prohibiting the retention of the same signified. We saw how, in L'Accordée de village, the success of the theatrical effect depended on the effusion, the affective expansion that characterized the four protagonists and was symbolized by the interlacing of their hands. This effusive power, turned towards the Other, bent over, embraced, intertwined with him, is inherent to visual theatricality, but can only break with the classical ideology of exemplum virtutis, which exalted constancy in trial, self-sacrifice as supreme courage. So it was in his drawing of La Mort d'un père, regretté par ses enfants, which he exhibited at the same Salon in 1769, and not in Septime Sévère et Caracalla, that Greuze succeeded in his transposition of La Mort de Germanicus : this time, the subject allows a happy shift from the rhetoric of ultima verba to the pathetic spectacle of a death that speaks for itself. The window reappears: outside, neighbors and friends continue the family's lament and figure in the effusive expansion. Inside, the father does not show what painting now forbids him to name he constitutes himself as an object of the gaze, reconciling at the heart of the canvas the viewer's scopic satisfaction with the painter's symbolic message, ambivalent like the color of the hands in L'Accordée de village : the assumption of the father in bourgeois ideology is at the same time, with the collapse of the old semiotic structure of visual space, its death.

Notes

" Le théâtre de Baudelaire ", 1954, in Essais critiques, Seuil, 1964, Points-Seuil, p. 41.

The painting is in Minneapolis, the Minneapolis institute of arts, the William Hood Dunwoody fund it is thought to have been painted between 1626 and 1628. Reproduction and technical note in the catalog of the exhibition held at the Grand Palais from September 1994 to January 1995, Nicolas Poussin 1594-1665, edited by Pierre Rosenberg, Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1994, n° 18, pp. 156-159.

Annals, II, 71-72.

The painting is in Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland it is thought to have been painted between 1627 and 1628. Reproduction and technical note in the catalog, op. cit., n° 22, p. 164-165.

The painting is in the Museum of fine arts, Boston it would have been painted in 1628 or 1630. Reproduction and technical notice in the catalog, op. cit., n° 23, p. 166-167.

The painting is in Detroit, the Detroit institute of arts, founders society purchase general memberschip and donations fund it is thought to have been painted in 1627 and possibly retouched in 1630. Reproduction and technical note in the catalog, op. cit., n° 37, p. 191-192.

The painting is in Hovingham Hall (Yorkshire), collection Worsley it is thought to have been painted around 1624-1625. Reproduced in Alain Mérot, Poussin, Hazan, 1990, p. 40. Commentary p. 38. Technical information p.276. Do not confuse this painting with the one in the National Gallery in London, which treats the same subject, without a curtain.

Poussin, for this distribution of space, is clearly inspired by the scene imagined by Ovid, Metamorphoses, XIII, 778-788.

Metamorphoses, XIII, 874-897. In Ovid's text, the moment of dramatic reversal is indeed the moment of seeing : " Me videt atque Acin : Video que exclamat et ista / Ultima sit, faciam, Veneris concordia vestrae " (v. 874-875) (He sees me and Acis: "I see," he exclaims, "and let this be the last time, I'll put a stop to it, that you find yourselves in love). Note the absolute use of video.

Catalogue Poussin, op. cit., p.166 : "Poussin may have subtly indicated the genitals "... A few centimetres away, the painter doesn't seem to have bothered with this kind of subtlety with his putti, to which the insults of time and the delicacy of the line have taken nothing away from their virility. As for Dempsey's considerations on Poussin's impotence... Misères de la critique positive !

It is by crushing, by (re)treading signifier (the crescent) that we produce or reveal signified (Diana). The signified is thus a crossed-out, crushed, repressed signifier.

J. Lacan, Le Séminaire, book XI, " Les quatre concepts fondamentaux de la psychanalyse, 1964 ", Seuil, 1973, pp. 82-83, p. 86.

R. Barthes, La Chambre claire, Cahiers du cinéma-Gallimard-Seuil, 1980, pp. 47-49, p. 79-80. Unlike R. Barthes, we believe that the punctum is not an exclusively photographic effect, but more generally a founding element in any modern visual device, whatever its medium : painting, cinema, advertising, literature playing on the visual... This brings the Barthesian punctum closer not only to the anamorphic object constitutive of the Lacanian tableau, but also to the Derridean supplement. Although they hardly quote each other, the three notions were in fact conceived at the same time and in the same intellectual context by all three men.

We repeat here Anne Larue's analyses of the theatrical stage, paper presented at the TIGRE seminar on November 5, 1994.

J. Lacan, op. cit., p. 95.

Ibid., p. 93.

Ibid., p. 70.

That the transgression of the screen by the gaze has to do with the phallus is shown by the drawing from the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, which depicts Theseus abandoning Ariadne. The curtain enveloping the bed where Ariadne lies while Theseus, kneeling at her feet, straightens up to leave, is held in place by a term, a column in the shape of a bust statue with clearly visible sex, whose meaning as erected phallus is hardly debatable. See catalog, op. cit., n° 33, p. 185. The notice rightly compares the term to the figure holding the curtain in La Mort de Germanicus ; but the position of the raised arm then seems to us to preclude identification with a statue.

Ibid., p. 93.

" Et erant qui formam, aetatem, genus mortis, ob propinquitatem etiam locorum in quibus interiit, magni Alexandri fatis adaequarent. " (Annals, II, 73, 1.)

A. Mérot, Poussin, Hazan, 1990, p. 39.

On this subject, see Plutarch's Life of Alexander, § CXXIII.