To designate what we mean today by mawkish and mawkishness, we used to speak in classical language of mignard and mignardise. It's the word Diderot used to castigate Boucher and the rococo style:

" What colors ! what variety ! What a wealth of objects and ideas ! This man has everything, except the truth. [...] His elegance, his cuteness, his romantic gallantry, his coquetry, his taste, his ease, his variety, his brilliance, his faded complexions ; sa débauche, doivent captiver les petits-maîtres, les petites femmes, les jeunes gens, les gens du monde, la foule de ceux qui sont étrangers au vrai goût, à la vérité, aux idées justes, à la sévérité de l'art " (Salon de 1761, DPV XIII 222)

Mignardise is an exercise in libertine style, which has nothing to do with the virtuous program of mawkishness. Mièvre nevertheless existed in the classical language it is attested by Trévoux's Dictionary as early as the 1738 edition :

Mièvre, adj. m. & f. Alacer, malignus. A popular term applied to children who are alert, restless and malignant, always doing some mischief or mischief to others. A boy who is miévre at the age of ten or twelve is no better ; it is a sign of spirit & courage. This word is low.

In Normandy we say niévre, from which Ménage concluded that miévre comes from nebulo, meaning garment.

Miévreté. s. f. Fraus, puerilis alacritas. A little niche or mischief, which a miévre child is wont to make. It is low. (Dictionnaire de Trévoux, ed. of 1738, t. IV, col. 1259)

The word is therefore popular and low ; it is linked to childhood, but does not immediately designate the blandness of mignardises. Before the " little niche or mischief ", there is first an energy of mawkishness : " it's a sign of wit and courage ", it's the quality of garment. Mièvreté, not mièvrerie : through this punctual annoyance that it identifies as a customary trait, language takes hold of something that emerges on the intimate scene, which we hadn't bothered to characterize until now. With the advent of mawkishness at the end of the century, childhood gained access to representation, first as an accessory to the genre scene, then as a central subject, and finally as a proposal for a global norm: a representation that would be conceived by the yardstick of childhood, in the fiction of its point of view and with the codes that society elaborates for it1.

Marillier plays an essential role in this emergence. His style and his entire body of work responded to the call of the mawkish, at a time when a public of children's readers was being built up : here are sketched out the canons of illustration for young people2, even though these images, those of the Cabinet des fées, the Voyages imaginaires, and even more so the novels and plays Marillier illustrated, were not primitively intended for them.

Marillier was thus involved in a veritable conversion of representation, which should not be reduced to the birth of a genre or a product, a children's literature that would take its place alongside other bookshop categories it was the whole of culture and its representations that shifted and changed age, and went to use childhood as a supplement to collapsed propriety. Merging and transforming the courtly etiquette of Baroque novels, the aristocratic dilemmas of tragedy, cases of /// gallant conscience, into a single gobal norm, mawkishness, with its demands for virtue and sensitivity, becomes the new code3.

Rococo mignardise had developed against the grand genre, in the shelter of pastorale and fêtes galantes in this fin de siècle, mièvrerie absorbs all genres and seizes first and foremost barbarism. A mawkish barbarism would be a barbarism that could be placed in all hands : say it all, show it all, sanitize it all4.

I. Mild barbarism

The ability to represent barbarism was, in the classical age, a prerogative of the great genre, heroic and tragic. The low style of comedy engaged not only low characters, but low actions : when the pastoral features crimes and sacrifices, it becomes tragic. With the emergence and development of fables and tales, this polarity of high and low styles became blurred and blurred: the exoticism of fiction paradoxically authorizes the familiarity of representation and democratizes barbarism anyone can, with the greatest of ease, have their head cut off5.

What is a mawkish decapitation ? It's the exercise of a gentle barbarity, not because it's human, but because of the ease of its advent, the fluidity of its course, the lightness of its acceptance. The expenditure of affect, for reader and spectator alike, is measured, and the horror is attenuated and softened. The framework of the tale authorizes it, and at the same time limits its brutality.

Let's have a look instead.

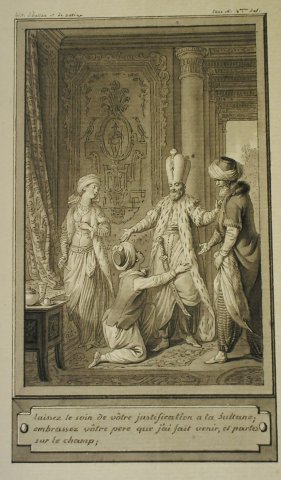

Quoutbeddin (XVI, 2)

The cabinet is cramped, or we're in its most remote part. The rich carpet and painted wood facings of the walls contrast with the absence of furniture6. There's little more than a mattress, on which an old man with a white beard and turban lies. A young servant on the right brings him a cushion to straighten him up. To the left, two servants light the scene with their torches. In the foreground, a Turk wearing a fez strides forward, rushing even sword in hand, brandishing a decapitated woman's head which he holds by the hair.

The scene is eerily tranquil. All eyes are fixed on the central, horrifying object, on this decapitated head. Yet none expresses horror or amazement. A little astonishment perhaps in the gaze of the reclining old man, who points to the head with his right index finger. The young man with the cushion has paused for a moment in his work of arrangement the torchbearers remain imperturbable the executioner is hurried no backward movement, no retching, the barbarism is carried out amiably, the unspeakable is a done deal. Is this the head I asked for? Yes, it is. - So let's give her her reward, and move on.

It has to be said that the story lends itself to this temptation of mawkish insouciance : The king of Syria, Quoutbeddin, falling madly in love with his visir's daughter, rose-cheeked Ghulrouk, catches her bantering with a page. Quoutbeddin is drunk and seized with fury, ordering her to be seized and beheaded. The scene Marillier illustrates here is the one in which, a few hours later, the executioner returns "loaded with une tête pâle & /// bloody ". The indefinite article is a red flag... Having recovered from his drunkenness, Quoutbeddin violently regrets his impulsive outburst, withers, and speaks of renouncing the throne. The visir then reveals that it is not his daughter Ghulrouk who has been beheaded, but a wretched convict from the city's prisons. Ghulrouk is returned to the king, and all is well.

The head is therefore not the real head that counts, that of the visir's beloved daughter, but a worthless head, which can be looked at with indifference. The tragic scene is not acted, but mimed, represented in the second degree, blunted as it were in its relationship to the brutality of reality. Marillier could draw on the repertoire of the grand genre7 : for example, Perseus brandishing Medusa's head to petrify Phineas and his companions, who have come to claim his fiancée Andromeda8. Ten years after Marillier, the anonymous illustrator of Aline et Valcour would return to the serious horrifying basis of the scene, at the end of the novel, to evoke Valcour's nightmare, the ghost of M. de Blamont, father of his mistress Aline, brandishing before him the bloodied head of his daughter9. Indeed, a few letters later, Julie will find her mistress Aline suicided, drowned in her own blood10.

So there's a scene of blood and horror, which the tale recovers, attenuates, adapts, softens. Marillier's immature characters11, either beardless, assexual teenagers or old men, are perceived through the prism of childhood, unaware of its youth and distributing its interlocutors into only two age classes, the normal (without type) and the old. The barbarism they portray is mawkish, i.e. reiterated in the register of childhood, not censored, but somehow deformed in the game of mawkishness. It's not just a question of the characters' expression. In these childhood fictions, the space is enclosed, stifled, barred, without perspective: it's the space of the bedroom, at once warmly caulked, familiar, close, and saturated with anguish because there's no way out. A scene that would have been walled up.

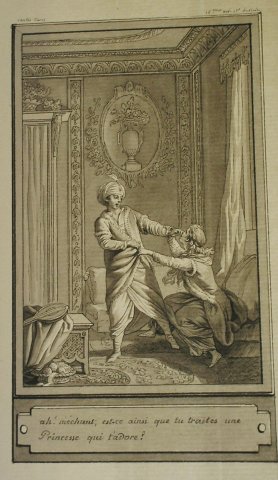

Hassan and Zatime (XVI, 3)

Here now is the vestibule of an oriental palace. Chinoiserie adorns the back wall in the background on the right, a colonnade in the Egyptian or Persian style leads to the outside on the left, the long drape of a flowered curtain hints at the opening of a window in front of which are arranged a bench and a sideboard supporting a teapot, an upturned cup and a strange pitcher the floor is covered with a thick carpet. Here again, although the stage is theoretically open at the back and left to the outside, these openings are virtually barred to the eye12.

;

;

Young Achmet, but that's /// Rather, a child we see here has thrown himself at the knees of Sultan Suleiman, who opens his arms to forgive him. On the right, Achmet's father, Amulaki, steps forward to relieve his son. Achmet's sister, Attalide, stands back on the left, shyly lowering her eyes.

In theory, the scene is of the utmost pathos. L'Histoire d'Hassan et de Zatime, 6e history of Voyages de Zulma dans le pays des fées by Abbé Nadal13, begins with the exile of Hassan, bacha of Chio, and the enslavement of Zatime, his wife, pursued by the vengeance of a spurned lover. Their daughter Almansine, sold to the visir of Sultan Soliman, is delivered to him instead of his own daughter Attalide to become his concubine. All the elements of a tragic oriental story are thus brought together, which the mawkishness of the new genre that developed throughout the Enlightenment will endeavor to soften: Soliman is an enlightened and sensitive despot, who respects Almansine's virtue. After Almansine for Attalide, it's Achmet, the visir's son, who passes himself off as her sister when the sultan again demands that she be handed over to him Achmet thus finds Almansine, whom he loves and is loved by the two flee on a boat to Smyrna. The sultan finally has the visir and his daughter delivered to him, with whom he immediately falls in love. A Soliman frigate arrests the fugitives' boat: Achmet is arrested and brought before the Sultan, who forgives him: this is the scene that Marillier illustrates, where the prince reunites the family and satisfies his desire only at the price of this reunion. The outstretched arms of the four figures form the family circle, uniting and somehow equalizing the kneeling child (Achmet) and the majestic sultan, wearing tiara and ermine cloak, the blushing accordion (for Attalide), Marillier recalls Greuze14) and the gardening visir15.

Thrown at Suleiman's knees to receive his punishment, Achmet is reunited with his sister and father. The vengeful despot turns out to be his benefactor, the tragic horror turns into the bourgeois tranquility of a family reunion. But above all, the circle closes: Marillier's visual circle is matched by the circle of substitutions used in the story: Almansine for Attalide for Achmet; the difference between the figures falls away, they are interchangeable, indistinguishable. Without the interplay of differences, passions cannot be expressed. Sensitive contagion, on the contrary, provides a virtuous normalization of identities.

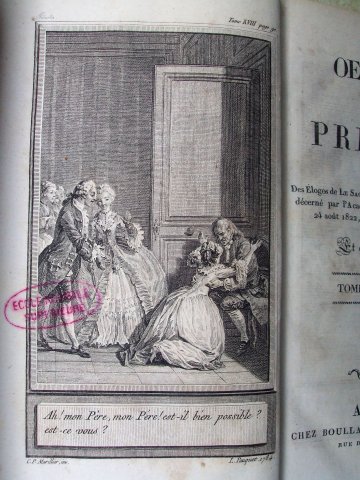

The major project that occupied Marillier prior to the Cabinet des fées was the illustration of Prévost's complete works, featuring a two-volume translation of Richardson's Paméla16. The edition follows the same principle as that of Cabinet des fées, with two engravings per volume : among the four engravings devoted to Paméla, Marillier chooses to illustrate the reunion of Paméla and her father, under the auspices of Mr B. In a completely different setting, the narrative plot is the same as that of Histoire d'Hassan et de Zatime : a despotic master (Mr B., Soliman) first tries to seize a virtuous young girl (Paméla, Attalide) by force he finally renounces force, /// forgives the would-be rival suitor (Pastor Williams, Achmet) and returns the father of the family (Mr. Andrews, the visir Amulaki). Undoubtedly, the scene is not the same, and Marillier arranges the characters differently: Mr. B is only the spectator, on the left, and Mr. Andrews, on the right. B is merely the spectator, on the left, of the reunion on the right of the daughter at her father's knee17 Soliman on the other hand occupies the center of the composition, while Attalide and Amulaki, who attend Achmet's supplication as spectators, spread out on either side of the central couple.

.The fact remains : the game is the same. The image ignores the narrative difference of what's played out first between Pamela and her father, then between Achmet and the sultan. It's always a child at the feet of a grown man, who becomes tender, abdicates his power and gives way to his sensitivity. It's also a gentle contagion, a tenderness that's communicated from one character to the next. Finally, it's a closed space, or more precisely, a deceptively open one: in both cases, the back wall blocks the perspective, in a scenography pioneered by Greuze18. The outside, the vague space of the offstage, are suggested by the door in the Paméla engraving, the colonnade in that of Hassan and Zatime, like a memory of the classical stage. But that's not what it's about, the depth of the vanishing point that once made it possible to articulate the scene captured in the foreground to the far reaches of the world and the sequences of the narrative19. The image in the book becomes an intimate image, taking on the contours of the space in which it is read, a secluded, protected space in which to give free rein to the fictions of virtue and its sensibilities. If it's a palace, it's a boudoir, a staircase, a backyard or a dungeon if it's a forest, it's a garden, a grotto or a sunken path ; and when, exceptionally, Marillier sketches an urban perspective for an outdoor scene, he erects a half-height wall that strictly delimits the stage path of the characters in the foreground20.

II. The stage as artifact

This tightening is not a suffocation. There's no oppression in these lively drawings, but rather a reduction, which is also a normalization. Whatever the place of the fiction, the fantasy or enchantment of the story, the aim is to reduce the material to a familiar, thoughtful stage device: the depth of time, the path of journeys are retracted in favor of the conventional surprise of an encounter, the simplicity of a face-to-face encounter.

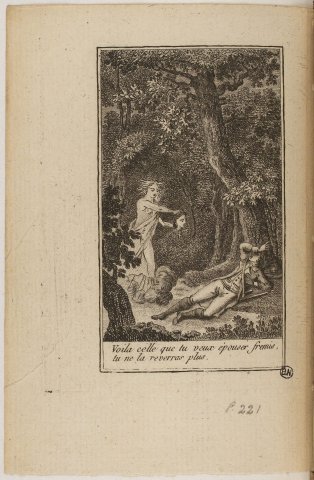

Boca, or virtue rewarded (XVIII, 3)

In the story of Boca, by Françoise Le Marchand, Marillier chooses to illustrate an enigmatic scene whose meaning will only become clear in the final pages of the tale. Boca, a poor young Peruvian sculptor, has been engaged by a series of prodigies on a long journey to the Orient. In Java, he first thinks of embarking for Japan, but he is led onto a boat controlled by insects and steered by birds, which takes him to an unknown but laughing shore. Boca crosses a forest in search of a place to spend the night. At the point in the text where the illustration is inserted, we read :

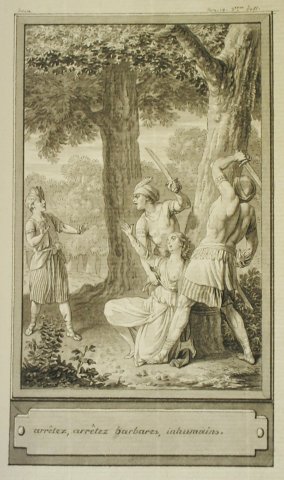

"It was about four hours ago that he was walking without turning from the main road, when painful cries, which penetrated to the heart, caused him an emotion /// The further he went, the more the cries increased. How frightened he was when he saw a woman being tied to a tree by two men. Then, a pity stronger than fear making him forget that he was unarmed and defenseless, he ran to her with ardor; and seeing that the cruel men were both drawing their sabers to strike this unfortunate woman: Stop, he shouted, stop, barbarians, inhumans.

At these words, the men, glaring at each other, shouted: "Stop, stop, barbarians, inhumans! At these words, the men glared terribly: "Be our first victim," they said, "die, you wretch. Immediately, raising their arms on him to immolate him to their fury, they both remained motionless, little did Boca fail to resemble them, awaiting the blow ready to fall on his head : however, reassured by the prodigy which had just guaranteed his days, he felt succeeding his fright a mortal displeasure: he had just stopped. " (Cabinet des fées, t. XVIII, p. 355-6)

Boca's pity, the terrible looks of the cruel spadassins with raised sabers, all the ingredients of the tragic scene are present in this text, right down to the suspended time of the pregnant moment. The story insists heavily on this suspension. On the one hand, a mysterious force stops the two men in their tracks; they remain petrified, as if the narrator had foreseen their pose for the painting21. On the other hand, Boca, gripped by this encounter, interrupts his walk, and this interruption constitutes a threat : a mysterious instruction has indeed been given to him at the time he undertook this journey :

"Don't stop on the way,

Whatever obstacles you find,

Boca, to work miracles,

You'll just have to be human." " (Ibid., p. 340)

Young Zineby, whom he unties, reassures him : he stopped his walk out of humanity in the face of the peril that threatened her the second injunction, of humanity, outweighs the first, not to stop. Nevertheless : the pause threatens the narrative, indicates the picture, and in a way programs the illustration.

There's no sign of fatigue on the child's face Marillier draws for Boca he sketches, with his two arms stretched out in front of him, a frightened retreat in the face of the horror of what's about to unfold before him. But his fright is moderate. On his belt, we can barely make out a small stick, the ebony staff whose magical power we learn, at the end of the story, is what immobilized the two evil genies of Kiribanou, the persecutor of Princess Abdelazis and her follower Zineby.

.In contrast to the face of Boca Marillier prints on Zineby's face all the marks of horror : raised eyebrow, dilated eye, open mouth. But this face is an empty mask. The young girl looks neither at her attackers, nor at her savior. The barbarity that is about to befall her is neutralized by Françoise Le Marchand's narrative : the assailants will never strike because the little magic stick is more powerful than the two swords the fairytale world absorbs the tragic scene, but defuses it the little wooden stick reduces the barbaric threat to child's play.

.Finally, Marillier's drawing reveals nothing of Boca's journey. No boat, no shoreline in the background the path itself is not clearly marked. The forest encloses the characters. In F. Le Marchand's story, Zineby could only have been boarded by the two Kiribanou genies because, having set out to meet Boca, whom she knew was coming, she left the invisible protective enclosure they could not cross. The scene of mock barbarism turns out to function as a threshold22 : for Boca, it's a question of penetrating this retreat23 inaccessible, forbidden to men, from which all fiction is built. This is where /// Princess Abdelazis has always been locked up, first as the fiancée of Prince Jealous, who wished to hide her from prying eyes, then, turned into a statue by him when he learned of her infidelity. In this retreat, palaces are domes24, gardens ovals25 : compartment reigns, with its folds, its secrets, its invisibilities.

Florine (XIX, 3)

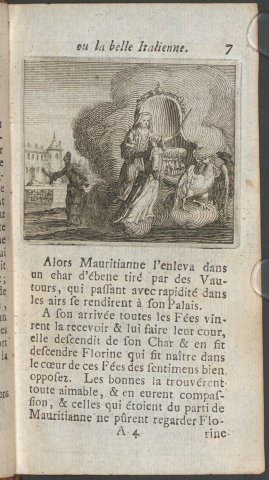

The theatricality of the scene of Zineby preying on the two spadassins screens this protected area. It is the last artifact of the heroic and the visible before penetrating the bocage, the invisible, the feminine. The same motif of invisible protection can be found at the start of Florine, another tale by Françoise Le Marchand, which Marillier illustrates by choosing the same moment of perilous crossing. Florine is threatened by the fairy Mauritianne (like Abdelazis by Kiribanou), and her castle has been surrounded by an invisible protection that Mauritiane cannot cross. So the fairy lures her out through subterfuge:

Mauritianne's castle has been surrounded by an invisible barrier that Mauritiane cannot cross.

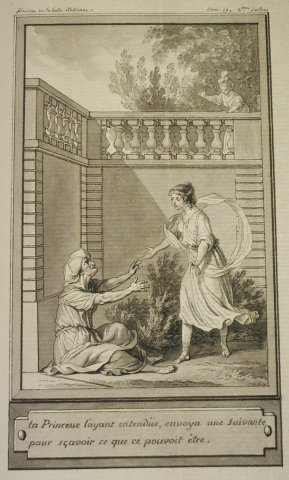

" Mauritianne stayed in the vicinity of the castle ; & one day when she spotted the princess walking on one of the terraces of the enclosure, she assumed the figure of an old woman, complaining like a person overwhelmed with pain. When the princess heard this, she sent her assistant to find out what it was. She reported that it was an old woman lying on the ground, looking very ill, and asking for help. The princess ran to her. Mauritianne, seeing Florine outside this enclosure, seized her with one hand, and with the other, traced a mysterious circle around her, and immediately they were enveloped in a thick cloud, which hid them from the eyes of the following woman" (Cabinet des fées, t. XIX, p. 379.)

In the left foreground, the old woman seated at the foot of the enclosure here materialized by a high wall topped by a balustrade has assumed the posture of a beggar who excites pity. On the right, Florine's next-in-line steps forward to meet her, stretching out her arms towards her it's a beautiful scene of emotion and sensitivity. At top right, Florine watches the encounter from behind the balustrade, her body leaning forward, her right hand raised in a gesture of invitation and already abandonment : as with Boca, humanity prevails over the forbidden.

Technically, Marillier draws a classic voyeuristic break-in scene : in the foreground, two characters come into contact, interact, handstretched against handstretched, in a space sharply delineated by the surrounding wall and the old woman's magic wand lying on the ground within reach behind the balustrade, Florine, from the vague of offstage, envelops the scene with her gaze. She has ordered this meeting, she circumscribes it with her gaze. Formally, Marillier resorts to the most classic scenic device, the layout of which can be found, for example, in Le Rendez-vous à la fontaine by Jean-François de Troy26 : in the foreground, below, a lover whispers sweet nothings into the dreamy ear of his mistress, who is dipping her fingers in the water of a fountain above them, behind a balustrade, a maid who was keeping watch leans over to warn them that someone is coming.

Before, then, the sensitive contagion, the effusion ; behind, the attentive, entrenched gaze, cut off by the screen of a wall, an interposed separation. But as much as Jean-François de Troy's cute scene concentrates libertine material /// Marillier's mawkish scene proves to be an illusion, in which the old woman is not an old woman, and the young girl in the foreground is not the heroine. The whole scene merely imitates the threshold Florine is about to cross. As in Boca, the illustration balances the tableau-like moment of humanity, but as a lure that traps the gaze, against the injunction to move, coming from outside, from the vague, the distant, but stopped by the scene if the maid timidly invokes urgency, absorbed in who knows what contemplation to the left, upwards, the lovers inscribe themselves in an entirely different temporality, slow and gentle, dreamy and sensitive.

The first Cabinet des fées in eight volumes, printed by E. Roger in Amsterdam in 171727, illustrated Florine with an exceptional and unpublished series of twelve engravings. Marillier takes up the narrative sequence exploited by the first engraving of 1717, which however depicts the scene a few moments later, when the marvelous, retracted in 178528, invades the scene. More than half of the engraving is taken up by the swirling clouds enveloping the fairy's flying chariot. Florine, already in Mauritianne's thrall, prepares to board, while her maid at far left watches helplessly from behind the cloud as she is abducted. The restricted space of the magic cloud is the space of fiction and action, from which stand out to the left, with all the effects of a perspective depth that tells the distance of fiction from reality, the maid who runs, the castle enclosure, then the castle itself and the trees of its park.

If we compare the two illustrations, from 1717 and 1785, we see that Marillier, by choosing the moment of the ruse, of the bait, which precedes that of the abduction29, finds himself having to invert the respective positions of Florine and her maid, whom he makes the main figure. It's no longer the action itself that we see, but its artifact: we could believe that an old woman is asking for alms, just as we could believe, in front of Boca's illustration, that a young girl was about to be cut into pieces, in front of Quoutbeddin's that his beloved's head was being brought to the king, in front of Hassan and Zatime's that Achmet was awaiting death at Soliman's knees. Each time, something else is at stake: the scene functions as a threshold of normality, which the text will undo, soften, return to mawkishness. Normality here has nothing to do with the classical norms of verisimilitude and propriety, which defined the acceptability of fictional deviation as real according to a mannerist logic, it refers instead to a normality of the scene that has already been seen, known and catalogued, itself associated with a topicality of efficacy (heroic, tragic, sensitive), a palmares of intensity (the-Crébillon père effect, the-Richardson effect, the-Rousseau effect...). The code doesn't seek to be forgotten, but rather exhibits itself as a code, only to be disappointed later: from the barbaric or pitiful scene, a few clues (Boca's stick barely visible on his belt, the old woman's wand too short for a cane, Soliman's open arms despite his regalia), childhood features (the dollish faces, the disproportion of bodies and objects) guide the eye towards this smoothing effect that signals the artifact and precipitates the call of the mawkish.

III. Cabinet layout

Two /// years after Le Cabinet des fées, from 1787, appeared the Voyages imaginaires, with the same indication on the title page : " à Amsterdam, et se trouve à Paris, rue et hôtel Serpente30 ". This is also the indication for the Œuvres choisies de l'abbé Prévost published in 1783-1784, also illustrated by Marillier, who probably had a contract with this printer. Was it the same network that commissioned him to contribute to Regnard's Œuvres complettes (Paris, Veuve Duchesne31, 1790) ? From an aesthetic point of view at any rate, this production, which goes beyond the Cabinet and Voyages series of drawings alone, manifests a remarkable unity and coherence.

Everything should oppose, a priori, the Cabinet, its intimacy, its enclosure, its speculative withdrawal, to the Voyages and what they presuppose of journey and risk, projection and openness to the distant. In fact, the preface to Voyages imaginaires warns us from the outset that this opposition has no place :

" the traveler describes the lands he has traversed, gives an account of his discoveries, & tells what happened to him among peoples hitherto unknown & whose manners & usages he transmits to us: but the philosopher has another way of traveling with no other guide than his imagination, he transports himself to new worlds, where he gathers observations that are no less interesting or valuable. Let's follow him in his travels, and be sure to bring back as much fruit from our journeys as if we'd been around the world" (Tome I, Publisher's Warning, p.1)

The preface to Voyages imaginaires retrospectively explains the workings of the Cabinet des fées. The Voyages are neither a sequel nor another category alongside that of the Cabinet. They fix, objectify its framework : The cabinet is the place of the voyage32, of philosophical reverie from which the imagination projects its virtual journeys, in the form of the tale. Awareness of this projection marks the shift, here explicitly assumed, from an economy of the parcours (" the lands he has traversed ") to an economy of the transport (" he transports himself into new worlds "), from a discursive logic of the event (" the traveler [...) to an iconic logic of collection (" he collects observations "). These changes affect not only narrative technique, or the rhetorical dressing up of genre conventions ; they engage the very content of fiction : not the written text, since the vast sum of the Voyages, like that of the Cabinet, merely combines existing texts, but the imaginary apprehension of these texts, guided and informed by their selection, their arrangement in the collection, their illustration.

Reciprocal metaphors for discursive sequencing, the journey through the lands and the account of events are recalled here only to define the lures of fiction (a narrative), the artifact of a figure (a traveler), the form in which a material reaches us (the text). In reality, this material is a matter for the philosopher: one philosopher has imagined this, these imaginary journeys, has conceived the overall fiction of them another philosopher, the reader, will follow him on his errands and bring back from his reading the fruit of a journey. Global fruit, synthetic vision of a sum that is a tour (like " if we had gone around the world ") and not a journey33.

In classical aesthetics, the denunciation of narrative deception is carried out through the stage : the scenic space is the /// means of short-circuiting the line of discourse, globalizing and visualizing fiction. At the end of the Enlightenment, another space and another model replaced that of the stage. It's the cabinet, with all its avatars of withdrawal, intimacy, gentle reverie, anguished solitude : the bedroom, the boudoir, the grove (or the cabinet of greenery), but also the island, the cave, the tomb. The place where the reader stands and the place where fiction camps its protagonists merge the traveler in Voyages imaginaires unites the two characters under the figure of the philosopher. Robinson Crusoe, the first of the novels compiled in the Voyages, then becomes L'Isle de Robinson, from which it is a matter of retaining " the solitude of our traveler in the Isle inconnue " moreover " our traveler is going to descend into the tomb that is digging itself insensibly beneath his steps " (p.2). The medium of representation is no longer the stage, but, at the antipodes of theatricality, this space of invisibility that is at once a reading room, the unknown island34 and the tomb35.

The images, the impressions that fiction produces for this space, are informed, normalized by this medium : " spectacles made to tear sensitive souls ", " a gallery of sad tableaux to the truth, but interesting " (p. 2). The call of the mawkish is felt here : the pathetic effect of these spectacles, of these tableaux, only apparently reconcile the academic play of the expression of passions ; the sensitive heartbreak, the maesta voluptas triggered by the tableau of catastrophe, the voluptuousness of shipwrecks, are only possible from the retreat of the cabinet Better still, they represent this retreat, the collapse of the public space of representation, its conversion into a sensitive wrench, the introversion of the terrible, formidable wave of the world into the sensitive abyss of the cabinet : a post-pathetic abyss, in the form and figures of childhood36. It's from Rousseau and the Émile that the prefacer claims, recalling, in connection with Robinson Crusoe, that " the citizen of Geneva made a special case of it. In his treatise on education, he denies his Emile a library. [...] but the novel de Robinson is excepted from this general proscription it is the first work he orders him to read he even wants this book alone to compose, for some time, his entire library. " (p. 5) The exception made to Robinson constitutes, more than a praise, a symptom : inexorably, literature is sliding towards childhood, and with it its object, no longer the theatrical play of public and private, which constitutes the world of made men, but the oceanic play of travel and cabinet, which stands at the threshold of this world, and arranges its paintings like so many artifacts.

Marillier's first engraving for the Voyages imaginaires depicts Robinson standing on the shore of his island, turning his eyes to the side of his beached vessel, lying on its side, invoking God : " how is it possible that I have come ashore ? ". The journey, the path of the voyage, becomes incomprehensible access to the fictional island is an abyss, a shipwreck. What Robinson is looking at is the abyss of the sea, a vague spectacle that cannot make sense as a scene, but designates the threshold, so to speak, of the novelistic enterprise37. The aesthetic is already that of the Romantic walker (Friedrich38), operated by Laisné in 185239, to represent, at /// At the end of Père Goriot, Rastignac at Père-Lachaise defying Paris at his feet : a collapsed society, a career to be made. We find him drawn by Sidney Paget in 1901 for The Hound of the Baskervilles : he's Watson in a cape in the wind, contemplating the moor from a rocky promontory40.

For Les Songes d'un hermite, by Mercier41, Marillier illustrates the eighth dream, " Les lunettes ". A man who has just lost and found his glasses, dreams that he finds others " bien merveilleuses " :

" par leur moyen je pouvait, sans être apperçu, voir à découvert les pensées des hommes : elles se présenteoient à moi à travers ces lunettes, à-peu-près comme on voit les objets dans la chambre obscure. " (XXXI, p. 274)

The hermit's glasses are, in a way, a metaphor for the cabinet device that orders the entire representational machine at the center of which Marillier stands. The hermit's retreat (to which Rousseau gave a new, political and sensitive meaning), the space of retreat that is the cabinet, the medium of the camera obscura to which the interior of the mind is compared, define the oceanic movement of transport, the introversion operated by this device, through which the imaginary journey in the chamber can take place.

Le songe des Lunettes then presents us with a succession of portraits, from which Marillier chooses " la chambre d'un petit-maître " :

" Tout y étoit bouleversé. I saw on a table a broken fan, a box of pills, some books whose titles scandalized me, remembering that I was a hermit ; lists of merchants, a woman's portrait, a broken sword, several decks of torn cards, pots of ointment, & other similar objects. He himself was lying harriedly on a chaise longue; his face was pale and downcast, and he was pulling on one of his stockings, gazing complacently at his leg. No matter how hard I stared at the seat of his ideas, turning my telescope around and around, I could only see himself in miniature" (p.278).

We know this picture of the libertine's disorders, of which Hogarth42, Baudouin43, Moreau le Jeune44 made their trade. In this painting, however, Marillier introduces a difference he slides the portrait of a woman, whom Mercier imagined in miniature on a table, to the wall of the cabinet, overlooking the absorbed young man, looking at him reprovingly. This woman staring at him in the clutter of his room can no longer be the mistress whose portrait he has obtained. It's a family portrait watching over him, a mute mother in the face of an adolescent sulk.

Notes

On this integration of contradictory styles into an economy of collecting, see Aurélie Zygel-Basso, " Les frontispices tardifs de Baudet-Bauderval : un monument illustré (1780-1880) ". On the vogue for exotic illustration, see Stéphane Roy, " Mondes exotiques et luxe typographique : l'art de la gravure et la pratique de l'illustration ". On architecture, see Diana Cheng, " Ordres architecturaux et expression chez Clément-Pierre Marillier ".

Marillier took part in the illustrated series of Regnard's Œuvres complettes, 6 vols., Paris, Veuve Duchesne, 1790 (the last two engravings, Les Chinois and La Foire Saint-Germain).

Similarly, in the illustration of the King of the Black Isles (VII, 2), petrification stops the king at the threshold of the bed where the wounded lover lies. The king's wife, stretching out her magician's arm before her, bars his access.

For the Histoire de M. Oufle, par l'abbé Bordelon, retouchée et réduite par M. G., Marillier illustrates chapter 3, " Comment M. Oufle crut être loup-garrou, & ce que son imagination lui fait ". Having found a bear disguise, Mr. Oufle puts it on to scare his wife in her bedroom. But she's still busy with her maid, so M. Oufle takes a book from his library, Bodin's Démonomanie (XXXVI, 1), to wait. The space is the intimate one of the cabinet, with imagination and travel inhabiting the reader at its center : a bear in the bedroom.

On the brain as receptacle of the journey, see Nathalie Kremer, " Voyage au bout de l'imaginaire. Étude du discours préfaciel dans les Voyages imaginaires de Garnier ", in A. Duquaire, N. Kremer, A. Eche (eds.), Literary genres and anthropological ambition in the eighteenth century : experiences and limits, Louvain, Peeters, 2005, p. 135-147.

In a more pleasant form, it's in Songe X of Mercier's Songes et Visions philosophiques , the dialogue of the antiquarian and the Mummy of Semiramis (XXXII, 2).

., Le Père Goriot, Paris, imp. Simon Rançon & Cie, 1852.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Hound of the Baskervilles, serialized in The Strand Magazine, with illustrations by Sidney E. Paget, in the year 1901.

///See Mayer's Discourse on the Origin of Fairy Tales, and the analysis of its pedagogical impregnation by Kim Gladu and Andréane Audy Trottier, " Le discours des éditeurs ou le rôle pédagogique de l'imagination . le Cabinet des fées et les Voyages imaginaires ". Here we see that the effect of reading, intended for " the pupil " taken " in a tender age " is described in terms of an impression, which strikes, fixes and engraves in the mind, leaves " deep traces ". The model for reading is engraving, with all that this implies in terms of inner violence.

On the emergence of this canon, see Aurélie Zygel-Basso, " D'une somme à l'autre. Image et discours du canon merveilleux vers 1860 étude de /// case ".

This standardization integrates a priori incompatible styles : Gothic style on the one hand, with its fortified castles (the tower from Barbe bleue, I, 2) and knights in armor (Les Chevaliers errans, VI, 3), neo-classical aesthetic on the other with its antique-style colonnades (first version of Barbe bleue ; peristyle from Prince Ahmed and the fairy Paribanou, XI, 3, from Contes des génies, XXX, 2, or from Prince Désir, XXXV, 2 rotunda temple from Aventures of Aristonoüs, XVIII, 2 ; interior of a rotunda for The Princess Truck, XXXIII, 2 ; audience room in the Ionian syle for the History of Prince Titi, XXVIII, 3... etc) ; orientalist style finally, with its Ottoman palace interiors (Les Mille et une nuits, Les Aventures d'Abdalla by Bignon, Les Mille et un jours by Pétis de Lacroix, Contes chinois, Les mille et un quarts d'heure and Les Sultanes de Guzarate de Gueullette, Contes orientaux de Caylus, Continuation des mille et une nuits de Chavis et Cazotte).

This is how Marillier repels the representation of monsters, which remains exceptional : Green Serpentine (III, 2) and the dragon of the Engaging Prince (XXXII, 1). Again, the size of monsters, and animals in general, is reduced (the snake from Quiribini, V, 2, the eagle from Plus belle que fée, VI, 1, the lion from Chevaliers errans, VI, 3). On this subject, see Swann Paradis's analyses, " La faune ".

On the stereotype of barbaric exoticism, see Jonathan Hensher, " Exoticism and travel " : of seven beheading scenes, only the one in Barbe bleue is European.

With a few exceptions, Marillier strips down his scenes. This trend becomes even more pronounced in Voyages imaginaires. See Christina Ionescu, " Clément-Pierre Marillier et les Voyages imaginaires : traductions visuelles de succès de librairie d'Outre-Manche ".

On the persistence of academic expression of the passions in Marillier's drawings, see Kim Gladu, " Éloquence du corps et représentation des passions : la persistance de l'académisme ".

Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book V, v. 210-235 (cowardly supplication and death of Phineas).

Sade, Aline et Valcour, letter LXV from Valcour to Déterville, Gallimard, Pléiade, p. 1047.

Letter LXVIII from Julie to Déterville, p. 1092, also illustrated. This is the 16thth and final engraving, which appears from the 2ndth printing of the novel (see p. 1208).

On the drawing illustrating Blanche Belle by Chevalier de Mailly (V, 1), the young girl in the tower has no /// more than twelve years old. The young couple with the mandolin in the Histoire d'Aboulhassan in Les Mille et une nuits (IX, 1) are no older. The rider in Ricdin-Ricdon, by Mme L'Héritier (XII, 1) is so small that his foot barely reaches the stirrup, and it seems impossible for him to get off his horse alone. The examples could be multiplied...

Compare with Moreau le Jeune's engraving for Le Retour imprévu by Regnard : the three figures are in a paved courtyard, closed at the back by a wall they are heading towards a door, perpendicular to the left, of which only a slit can be made out. The caption reads: "Please go away, I won't let you go in there". The prohibition at the threshold is the chosen subject, the chosen image.

Augustin Nadal, Les Voyages de Zulma dans le pays des fées, écrits par deux dames de condition, 1734, in-12. One copy in Poitiers (Paris, Briasson, 1734), one in Besançon, one in Versailles (Amsterdam, Changuion, 1734), one in Fontainebleau (Amsterdam, M.-C. Le Cène, 1735, Bnf FB9526).

Greuze, L'Accordée de village, 1761, Paris, Musée du Louvre.

To please Attalide, Soliman gave up punishing Amulaki, his visir, and had him appointed gardener of the seraglio, so that daughter and father would not be separated.

Œuvres choisies de l'abbé Prévost, avec figures, in Amsterdam, and is in Paris, rue et hôtel Serpente, 1783-1784, in-8°. The translation of Paméla is in fact not by him.

Compare with the scene of Édouard asking Saint-Preux for forgiveness that Marillier illustrates for the London edition of la Nouvelle Héloïse, printed probably in 1781 (4 vols. in-8°, 2e of 12 plates, Toulouse, Bibliothèque municipale, CD48).

In addition to the Accordée de village, we can cite La Piété filiale (1761, St. Petersburg, Hermitage), the Septimus Severus and Caracalla (1769, Paris, Musée du Louvre), The Beloved Mother (1769, Madrid, coll. Laborde), Le Fils ingratand Le Fils puni (1777-1778, Louvre), but also lesser-known paintings such as La Veuve et son prêtre (Hermitage), La Dame de charité (1775, Lyon, Musée des Beaux-Arts), all barred by a back wall that blocks perspective and orders the composition into a frieze.

One may wonder whether Marillier respects, as Madeleine Pinault-Sorensen asserts, the rules of three-plan composition, which ensured the depth of scenes in classical academic aesthetics. The three planes are generally reduced to two, or at least the third is reduced to its simplest expression. See Madeleine Pinault-Sorensen, " La Flore ".

The Thousand and One Nights, Story of Baba-Abdalla, XI, 1. This is the only city scene in the entire series.

Marillier has already illustrated a similar petrification for the Histoire du jeune roi des îles noires, in /// The Thousand and One Nights (VII, 2). A young king discovers his wife's infidelity and mortally wounds her lover. She, who is a magician, half petrifies him: his entire lower body is turned to black marble. Marillier draws the moment of petrification, which stops the king's gesture brandishing his sword to strike.

" that if her zeal did not make her cross the bounds of a path she had prescribed, she could fear nothing, but that one step beyond, it was done with her days " (p.444-5) ; " So you were about to perish, my dear Zineby," she told him, embracing him, "when, at the sight of Boca, transported with joy & full of confidence, you ran to meet him, franchising the prescribed limits & forgetting the danger " (p. 450).

The motif of retreat is central in Le Cabinet des fées and even more so, as we shall see, in Les Voyages imaginaires. It has a very personal resonance for Marillier : the latter, between 1775 and 1785, did not in fact live in Paris, but on the Beaulieu estate he had bought for himself near Melun. See Amélia Belin, " L'œuvre de Marillier, genèse et réception ".

" a small domed building ", p. 365 " this domed sallon ", p. 367.

" a large oval of turf, on which a prodigious quantity of painted beehives " (p. 364) ; " a beautiful avenue of orange trees, which led him to an oval much like the one he had seen " (p. 369) ; " a large quantity of pineapples occupied the oval " (p. 370).

Jean-François de Troy, Le Rendez-vous à la fontaine, or L'Alarme, 1723, oil on canvas, 69.5x64 cm, London, Victoria and Albert Museum, inv. 512-1882.

On the Cabinets that preceded the one illustrated by Marillier, see Daphné Hoogenboezem, " Les Cabinets des fées avant celui de Mayer. Compilations of fairy tales published in the Netherlands in the 18th century ". Comparative analysis of the frontispieces enables her to identify the emergence of a cabinet device, where the myth of oral transmission of the tale is replaced by the model of childlike reading.

This retracting of an operatic set marvel, very present in the illustrations of the first half of the century, is systematic with Marillier. See Daphné Hoogenboezem, " La représentation du merveilleux dans les Cabinets des fées ".

This choice constitutes a normalization : the dominant moment of the scene, as theorized by Diderot and Lessing, is not that of the coup d'éclat, of the decisive conclusion (favored in Baroque aesthetics), but the weak moment of indecision, of suspense, of wavering, from which the spectator must project, complete the denouement.

There were actually two editions of Cabinet des fées du Chevalier de Mayer. See Dominique Varry, " Éléments pour une histoire éditoriale du /// Cabinet des fées ".

For the Veuve Duchesne, Marillier had illustrated the Œuvres complettes de M. de Saint-Foix in 1778, in a neo-classical style that then hardly distinguished him from other illustrators. By contrast, in the series of La Nouvelle Héloïse (London, 4 vols. in-8°, 1781), Marillier eliminates all the faraway places imagined by Gravelot (1761) and Moreau le Jeune (1774) : if we compare, for example, the three Baisers de Saint-Preux, we see that Marillier has done away with the pergola, whose factory made it possible to measure the depth of the scene, and installed his characters in a grove that is already that of the imaginary forests of the Cabinet des fées, with no perspective from which the eye can flee. For Saint-Preux à Paris (II, 26), Gravelot's urban view, Moreau le Jeune's staircase and open door give way to a boudoir scene with no visible door or window. To La confiance des belles âmes (IV, 6), which tiered shots of Clarens's avenue, gate and park, succeeds the effusive Julie's children jumping at Saint-Preux's neck, in a rotunda whose window is offended by curtains. Les Monuments des anciennes amours (IV, 17), with the view, from Meillerie, of the lake and Clarens, are replaced by Les Poissons de l'Élysée, whose bushy grove encloses the three protagonists, Julie, M. de Wolmar and Saint-Preux on their knees. Marillier thus already establishes the space of the Cabinet, but his faces don't yet have the mask of childhood they'll take on a few years later.

For Le Voyage interrompu, by Thomas l'Affichard (1st ed. Paris, P. Ribou, 1737), Marillier draws Abbé Damis interrupted in his study by his three friends Valsaint, Bourville and Climont, who invite him to a country party. The performance space is a library (XXX, 1).

On this organic logic of Voyages, see Aurélie Zygel-Basso, " Cartographier l'imaginaire : représentations de l'espace dans l'anthologie littéraire ".

The island is a common territory of Travel and Storytelling. See, for example, at the dawn of the genre, L'Isle de la Félicité by Mme d'Aulnoy (1690), or L'Isle inaccessible by Chevalier de Mailly (1698).

In its lugubrious form, it is, in the Voyage de Critile et d'Andrenius, translation of Balthasar Gracian's Criticon (1651), Critile's descent, with his sixth-sense companion Egenie, into " une Cave horrible " where he finds his errant friend Andrenio, half-dead among the corpses. Marillier's stylized drawing /// Gracian's allegorical cellar with three arcs of a circle representing its vault.

For L'Isle inconnue, ou Mémoires du chevalier des Gastines (actually by Guillaume Grivel, ed. original from 1783), Marillier depicts a children's scramble worthy of our playgrounds : Henri jostled by Baptiste (left) has fallen to the ground and skinned himself Adélaïde wipes his face with a handkerchief. Love's spite does not take the form of a scene, but a childhood tableau (VIII, 1). The volume's second engraving shows Guillaume bringing Philippe back in a rowboat, saved from drowning, while the wounded Joseph waits for them on shore. The shipwreck is transposed into childhood, no doubt with the attraction of La Nouvelle Héloïse (L'Amour maternel by Gravelot, which in 1762 came to replace La Mort de Julie, the 12the engraving in the 1761 series).

In this respect, the second engraving, which depicts Vendredi's submission to Robinson, merely redoubles the first : faced with the upright lone traveler, primitive barbarism is another figure of shipwreck, of social catastrophe. In the background, we can make out the cannibals.

Hugo Friedrich, The Walker above the Mists, 1817-1818, oil on canvas, 94.8x74.8 cm, Hamburg, Kunsthalle.

First edition : Louis-Sébastien Mercier, Songes d'un hermite, A l'hermitage de Saint-Amour, Paris, Hardy, 1770, in-12, coll. " Bibliothèque de campagne, ou Les amusemens du cœur et de l'esprit ", n°18.

In the Marriage A-la-mode series, the second painting known as The Tête-à-Tête (69.9x90.8 cm, 1743, London, The National Gallery) sets the scene for the next day's breakfast, where the exhausted, livid groom slumps in his chair, his shrouded sword thrown at his feet. Hogarth creates the figure.

The Exhausted Quiver, 1765, depicts, facing a courtesan reattaching her bracelet, a seducer slumped on a sopha, sword on the ground, following Hogarth's model.

In Le Lever, 1775-1776, people are busy around the petit-maître who is winding up his stocking.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Marillier, l'appel du mièvre » (Postface), Imager la romancie, coll. La République des Belles Lettres, dir. Aurélie Zygel-Basso, Hermann, 2013, p. 427-449.

Fiction, illustration, peinture

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Fiction, illustration, peinture

La scène de roman

La scène de roman : introduction

Renaud dans le jardin d’Armide

Rastignac chez Mme de Restaud

Gilberte derrière les aubépines

La poignée de porte de tante Berthe

La double aporie du topos

Illustrer la fiction

Molière, une parole débordée

Marillier, l’appel du mièvre

On n'y voit rien

Illustrations de l'utopie au XVIIIe siècle

Le temps des images

Du conte au roman graphique

Déconstruire l’illustration

Régimes de la représentation dans la gravure d’illustration classique

Penser la fiction depuis la peinture

Une sémiologie du décalage : Loth à la scène

Introduction à la scène comme dispositif : Paolo et Francesca

La main tendue, le regard démasqué

De Silène molesté à la chair blanche des nymphes

Chambres de la représentation

L'intimité de Gertrude

Brutalités invisibles

Parodie et pastiche de Poe et de Conan Doyle dans Le Mystère de la chambre jaune de Gaston Leroux

Le dispositif de la chambre double dans Les Démons de Dostoïevski

Scène pour voir et chambre des brutalités

La Princesse de Clèves

L’invention de la scène dans le roman français

La canne des Indes

L'aveu

La princesse, la religieuse et l'idiot

Richardson

Entre scandale et leurre

Introduction aux Lettres angloises, ou histoire de miss Clarisse Harlove, par Samuel Richardson