Optics and metaphysics of Descartes

The word "geometrical" is not a modern invention. A definition can be found in the article PERSPECTIVE in the Encyclopédie, signed by the Chevalier de Jaucourt:

"Before entering into greater detail, it is apropos to know that we call geometrical plane a plane parallel to the horison, on which is situated the object we wish to put in perspective; horisontal plane a plane also parallel to the horison, & passing through the eye; land line or fundamental, the section of the geometrical plane & of the picture; horisontal line, the section of the horisontal plane & of the picture; point of view or main point, the point on the picture on which a perpendicular led from the eye falls; distant line, the distance from the eye to this point, &c. "

We can see from this definition that the geometrical plane forms the basis from which to build perspective in a painting. The geometrical plane is entirely dedicated to the object, and is thus opposed to the horizontal plane, which starts from the eye.

However, the notion of the geometrical field is essentially borrowed from Jacques Lacan's Seminar XI, entitled The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis (see VII, 3). Lacan introduces this notion as follows:

."It's not for nothing that it's at the very time when Cartesian meditation inaugurates in its purity the function of the subject, that this dimension of optics develops, which I'll distinguish here by calling geometrical." (P. 80.)

Lacan thus parallels the metaphysics of the philosopher Descartes, which develops around the famous "I think therefore I am" of the Discourse on Method (Part 4, Garnier p. 603), and the work on optics by the geometer Descartes, notably the Traité de l'Homme and La Dioptrique. Descartes' reflection on the workings of the eye and vision would be another way of saying what it is to be a subject, what it is, in all its purity, to be the function of the subject.

Or Descartes analyzes in a very particular way, and we might as well say right away that it's very exotic for us today, this functioning of vision. It's all a question of lines, which are transferred point by point from real external space to the internal space of representation. The human optical apparatus, the machine of the eye, according to Descartes, is a machine that transposes points.

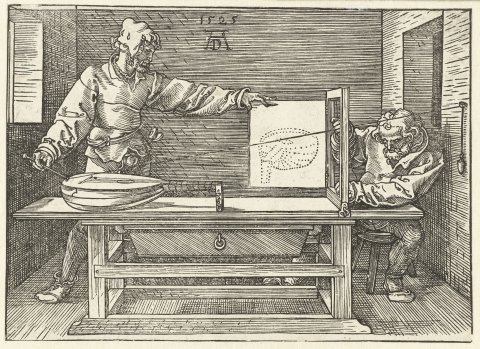

A point-by-point translation: Dürer's gate

We're thinking here of Dürer's device for reproducing a lute in perspective by means of a needle and a taut thread, the thread metaphorizing the path of light through which vision is constituted. Lacan alludes to this device a few paragraphs later. However, in what Lacan calls "Dürer's wicket gate", all the variations in the thread start from a fixed point, the pulley fixed to the wall:

."the point-by-point correspondence is essential. What is the mode of the image in the field of vision is therefore reducible to this very simple schema that makes it possible to establish anamorphosis, that is, to the relationship of an image, insofar as it is linked to a surface, with a certain point that we'll call a geometrical point." (P. 81.)

The model for point-by-point transposition is anamorphosis, which Descartes' era was crazy about. To distort the original image, anamorphosis transposes the features of one surface onto another, point by point. The translation is performed as follows: a single geometrical point is defined. A straight line is drawn from the point of origin to the target surface, passing through this geometrical point. The point of origin varies, but the geometrical point always remains the same.

Geometrical reduction

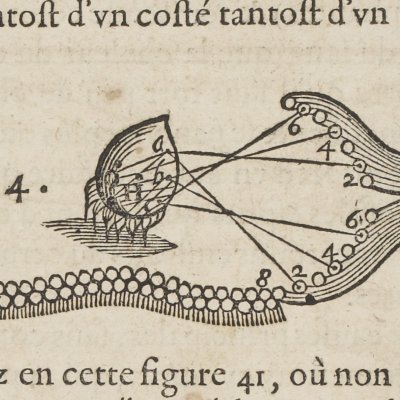

In Cartesian optics, the eye is an anamorphic machine: the geometrical point is in the eye. The totality of what is seen passes through this point to retrace itself, point by point, in the inner surface of the eye, then, in the center of the brain, on the pineal gland (Traité de l'homme, fig. 29, Garnier, p. 448).

Such modeling of vision is, in a way, the culmination of research into perspective carried out since the early Renaissance, notably by Alberti. It's no coincidence, then, that I mentioned Dürer's device precisely as a method of correctly reproducing perspective. As for anamorphosis, it's a play on perspective. The entire Cartesian theory of how vision works thus identifies vision with an experience of perspective.

Such a reduction poses a problem.

Such a reduction poses a problem, one that Diderot explodes in the Lettre sur les aveugles. I'm still quoting Lacan:

"Now please refer to Diderot. The Lettre sur les aveugles à l'usage de ceux qui voient will make you sensitive to the fact that this construction totally lets slip what it is about vision. For the geometrical space of vision [...] is perfectly reconstructible, imaginable, by a blind person.

What geometrical perspective is all about is locating space, not seeing"

Here we touch on the most important point of Lacanian analysis: the geometrical field considered on its own, autonomously, has no interest, no meaning. It doesn't even really account for vision, since it's a construction that a blind person can very well, very logically, make. Descartes' optics only makes sense in conjunction with his metaphysics, his theory of the eye only in conjunction with his theory of the subject.

Reduction, inversion, deformation: the function of lack

What the geometrical perspective highlights is the function of lack.

-

Firstly, the description of the entire mechanical process of vision assumes that the entire image passes through a point, that at a given moment, the entire surface of the image is reduced to the geometrical point. In art, in painting, this point finds its repercussion, its representation in the vanishing point. The image is ordered from this single point; but at the same time, it threatens to be reduced to this point.

- Secondly, passing through the geometrical point of the eye, the image reverses. The image actually inverts twice before reaching the brain. This double inversion is the necessary condition for the passage from the external image, in reality, to the internal image, in consciousness. It therefore presupposes a necessary work of negativity at work in the functioning of vision.

- Thirdly, by inverting twice, the image is not preserved as it was originally: passing from one plane to another, or from a space to a plane, the image is deformed. Perspective distortion is a fundamental principle of how vision works. All vision is anamorphic: Lacan then summons up the famous anamorphosis imagined by Holbein in the foreground of Ambassadors.

He points out that this deformed skull is reminiscent of both an eye and a sex.

"How can we not see here, immanent to the geometrical dimension - a partial dimension in the field of the gaze, a dimension that has nothing to do with vision as such - something symbolic of the function of lack - of the appearance of the phallic phantom?" (P. 82.)

The fascination aroused by anamorphoses stems from the fact that we find in them, amplified, the very principle of how vision works, i.e. both a borderline example of point-by-point transposition of the image and the evidence that we're dealing here with something quite different from point-by-point transposition. For what we see here is not the skull of death, but an erect sex. The representation of the ambassadors' world and its vanities is reduced to the skull of death to which they are necessarily destined; but the death signified to them reverses into aesthetic jouissance, the skull is turned inside out into a phallus. Finally, it's never definitively turned inside out; it's all about the movement from skull to phallus, from phallus to skull: it's in this deformation that the representation of the eye emerges. But here we're already touching on the scopic function, the scopic dimension of vision.

Critical function of the geometrical dimension

The geometrical dimension of vision, its mechanics, therefore only approaches what is essentially vision in a negative way. Through the establishment of perspective, it notes that everything is ordered and reversed from a point that is merely a technical point, a mechanical construct from which to reduce and then redeploy the image. But this geometrical point, which can be precisely designated in space, calls up another, imaginary point, the point of scopic neantization, by which the subject, looking at the image, becomes aware of himself as a crossed-out subject. The correspondence of the geometrical and the scopic, of the point technically arranged to bring perspective into play to the point fantasized as the negation of subject and meaning, is the correspondence of the optical model and the metaphysical model in Descartes.

.This is why establishing the geometric dimension of a painting composition cannot be reduced to describing the arrangement of figures and objects in a space. This arrangement must bring out the function of lack, and prepare the way for scopic crystallization. Lacan explains this in the following terms about the Ambassadors:

."It's further still that we have to look for the function of vision. We will then see emerging from it, not the phallic symbol, the anamorphic phantom, but the gaze as such, in its pulsatile function, bright and spread out, as it is in this painting.

This painting is nothing other than what every painting is, a trap for the gaze." (P. 83.)

The geometrical dimension does not account for the real function of vision, or it only accounts for it negatively, as for what unfolds beyond it, further on, in the scopic order. It is in the scopic order that we emerge from the antinomy represented by anamorphosis (a skull/ a phallus; death/ jouissance), to account for the "gaze as such".

What in concrete terms is this limit posed by the geometrical dimension, what is this threshold from which we enter the scopic? This limit is the limit of the trap: in the painting, the gaze is trapped. The geometrical dimension of the painting is the layout of the trap. From here, we leave Lacanian analysis behind, and I put forward my own models.

.A trap for the gaze: vague space, restricted space

I leave aside Holbein's The Ambassadors, which are a very particular and totally atypical case of spatial arrangement, and note that classical painting orders its compositions on the basis of a fundamental spatial distribution that it varies ad infinitum, but from which it almost never deviates: the space of representation can be broken down into a restricted, delimited, circumscribed space, and a vague, undefined space that circumscribes it. The restricted space is the place of representation that gives the painting its title; it is the place of the scene. The vague space is the landscape, the decorative background, everything that gives the painting its depth, but remains indifferent as far as its symbolic content is concerned. (Of course, in subtle compositions, the vague space also conveys symbolism: but this is a kind of gratuitous supplement, a superfluous trap, always based on the fact that, a priori, the vague space is the jewel case, luxurious but insignificant, that fades before the jewel of the restricted space.)

.This is not the place to detail the origin of this geometrical arrangement, which, from the end of the Renaissance to Romanticism, always necessarily orders the space of representation as a play between a vague space and a restricted space. I'll confine myself to a few schematic indications, which have no evidential value here, but will show you that the structures I'm positing are not arbitrary, and that I believe I can motivate them historically. On the one hand, the separation between vague and restricted space mechanically transposes to the secular domain the separation in the Tabernacle between the Holy and the Holy-of-Saints, which served as the basis for medieval Christian theology of images. On the other hand, the Renaissance transition from narrative iconography (depicting concomitant or successive episodes in the same image) to scenic iconography (centering the entire representation on a single scenic episode) did not happen abruptly: gradually, one episode emerged as the main one, and the other episodes slipped into the background, gradually becoming de-emiotized, purely decorative and vague. In classical times, vague space is the fossil of medieval narrative proliferation.

These two historical motivations for the typical classical geometrical structure are heterogeneous: but they converge towards the same articulation between a vague space and a restricted space, which is thus motivated both theologically and semiologically. In any case, the aim is to lead the gaze towards the restricted space alone, and to enclose it there. This is the function of any geometrical organization of a representational device.

To define this geometrical organization is therefore to define the modalities of the trap or, in other words, to highlight the screen or screens that articulate, regulate the passage from vague space to restricted space.

Critique et théorie

Archive mise à jour depuis 2008

Critique et théorie

Généalogie médiévale des dispositifs

Entre économie et mimésis, l’allégorie du tabernacle

Trois gouttes de sang sur la neige

Iconologie de la fable mystique

La polémique comme monde

Construire Sénèque

Sémiologie classique

De la vie à l’instant

D'un long silence… Cicéron dans la querelle française des inversions (1667-1751)

La scène et le spectre

Dispositifs contemporains

Résistances de l’écran : Derrida avec Mallarmé

La Guerre des mondes, la rencontre impossible

Dispositifs de récit dans Angélique de Robbe-Grillet

Disposition des lieux, déconstruction des visibilités

Physique de la fiction

Critique de l’antimodernité

Mad men, Les Noces de Figaro

Le champ littéraire face à la globalisation de la fiction

Théorie des dispositifs

Image et subversion. Introduction

Image et subversion. Chapitre 4. Les choses et les objets

Image et subversion. Chapitre 5. Narration, récit, fiction. Incarnat blanc et noir

Biopolitique et déconstruction

Biographie, biologie, biopolitique

Flan de la théorie, théorie du flan

Surveiller et punir

Image et événement