To quote this text

Stéphane Lojkine, " Les deux voies : scène et discours dans La Nouvelle Justine de Sade ", Le Roman libertin et le roman érotique, Les Cahiers des paralittératures, dir. Jean-Marie Graitson, n°9, 2005, p. 115-135.

Full text

Full text

No novel more clearly demonstrates its dual economy on first reading than the Sadian novel: discursive economy on the one hand, which unrolls and strings together both a succession of events (the narrative) and a succession of arguments (the discourse); scenic economy on the other, which stops, blocks the discursive unfolding to give to see, to make tableau, to arrange in space and no longer to string together in time.

Traditionally, this double economy has a subversive function: the discursive economy establishes a symbolic norm, a frame of reference, customs, mores, rites, laws, a system; the scenic economy transgresses this symbolic norm: technically defeating the discursive logic, it simultaneously questions the meaning, the validity, the spring of this norm. To move from the linearity of discourse to the device of the stage is to move from the establishment and repetition of a norm to the questioning and subversion of the norm. The stage thus constitutes itself both semiologically and symbolically (i.e., in its modes and in its object of representation, in form and in substance) as scandal: it produces the effect, the success of the novel through this scandal, because it is its Trojan horse, working against the discourse that has welcomed it into its midst.

Scene versus discourse, then, such is the classic use of the novelistic scene, discourse being understood in the very broad sense of discursive logic, of everything that connects, both narrative and argumentative discourse proper1.

No doubt that the Sadian scene is supremely scandalous, nor that this scandal, indeed the visceral horror it arouses, is one of the mainsprings, if not the fundamental one, of the fascination that the Sadian text exerts on its reader. But what norm does it transgress in the order of discourse, itself inhabited and colonized by the libertine's discourse, which merely prepares its advent and justifies its event? Sadistic perversion also works on a semiological level.

While the subject matter and rhythm of the Sadian novel seem to mimic that of any novel of the classical era, the articulation of scene and discourse has been profoundly perverted.

We'll begin by showing how the Sadian scene perverts the scenic devices it seems to mimic, tending to abolish the differential system by which they ordered both the system of looks and the production of meaning.

This abolition, this precipitation, this carrying away of the Sadian scene towards its own annihilation is paradoxically repaired by the discourse, which re-establishes a differential system of signification: in Sade there is not one, but two discourses, of vice and virtue, not one narrative route but two paths, which are also two competing sexual paths, the anal and the genital. It would be a mistake to underestimate, in the face of the libertine's speech, that of the victim, which plays its part both in the novelistic economy and in the system of Sadian thought.

.In a second stage, then, we'll consider the two paths of Sadian discourse, in their scenic articulation: let's posit our hypothesis from the outset; in Sade, the scene doesn't subvert the discourse, but articulates the two discourses, completes, one in relation to the other, their disposition.

What troubles and scandalizes Sade's reader, and especially the contemporary reader for whom the pornographic effect is perhaps somewhat worn out, might therefore not be the mere exposure of the most shameless sex scenes; but the participation, the implication of these scenes in the two discourses: we shall study this implication of the path of virtue in the scene of vice in a third step, showing how Sade here invents the modern writing of brutality.

I. The Sadian scene as a perversion of the scenic device

The requirement for painting is posited from the very first pages of La Nouvelle Justine:

"It is dreadful, no doubt, to have to paint, on the one hand, the frightful misfortunes with which heaven overwhelms the gentle and sensitive young woman who best respects virtue, on the other, the influx of prosperities on those who torment or mortify this same woman" (p. 3962).

The picture of the Justine's misfortunes is not given to be seen fortuitously, by breaking and entering; it has to be painted. Later, Sade speaks of "painting crime as it is"; Dubourg, the first libertine Justine meets, "was to be painted during this narrative" (p. 402). This demand for painting constitutes the framework of representation, inhibiting, conjuring up at the root by its repetition the prohibition of the gaze that the classical novelistic scene is wont to transgress.

Painting is therefore a law, the law of narrative:

"This is where the exactitude we have made a law for ourselves weighs horribly on our virtuous hearts: but we must paint; we have promised to be true; any dissimulation, any gauze would become an injury done to our readers" (p. 495).

It's hard to see how, from then on, the screen of representation3 would be constituted in the Sadian scene, whose function precisely is to interpose, between the spectator's eye and the unnameable thing at stake in the scene, the "gauze", the veil of modesty of a fictive mediation, of a mimetic displacement.

Sade resorts to a curious word: "any gauze would become a lesion made to our readers". To be injured is generally to suffer damage: the reading contract would not be fulfilled. But lesion implies much worse: the screen is identified with a wound, the very wound of castration that the spectator's scopic pleasure in front of the scene all at once recalls, repeats and conjures, displaces, attenuates.

The economy of the screen is thus perfectly known and accepted by Sade, but he disposes of it outside his own field of representation, or at the limit of that field. For the Sadian narrator, nothing is unnameable: this is the famous transparency of Sadian writing.

The screen is not part of the frame of reference, but subsists as the virtuality of the virtuous gaze, which is part while of the sadistic universe. If crime and its effects must be painted, there's no point in painting the soul of the virtuous:

"It is unnecessary to paint the effect this cruel deliberation produced on Justine's soul; our readers will easily understand it." (P. 435.)

Maybe we understand; but it won't be given to us to see. Justine's interiority remains in shadow:

"Nothing matched Justine's despair. We believe our readers now know her well enough, to be quite certain that it is useless to paint for them all that the obligation to follow such people made her feel." (P. 440.)

Sometimes, moreover, Sade leaves the peremptory assertion to confess his embarrassment:

"It is not easy to paint at once what our different characters were feeling here." (P. 496.)

So it's not simply a question of the thematic choice not to paint the soul of the virtuous. It's the very point of view of the virtuous, it's his gaze that's impossible to paint, because Sade knows, from the outside, that this gaze is confronted with a screen, thus faces the unrepresentable. Paradoxically, the Sadian unspeakable is not the Sadian scene, whose horrors are detailed with luminous precision, but the virtuous gaze cast over this scene.

Sade thus casts two gazes on the scene being performed. The first is placed under the injunction "il faut peindre" ("we must paint") and enters squarely into a scene without a screen: for him, for the libertine both spectator and actor, the scene becomes a tableau, is constituted as a picture into which he enters, but into which, by forced complicity, the reader enters with him.

"By turns, he insults, he flatters, he mistreats, he caresses. Ah! what a picture, Great God!"(P. 416.)

The second gaze is the one that Sade cancels out, or tries to neutralize by means of the opposite injunction, "it's useless to paint": it's the external gaze of the virtuous spectator. This gaze exposed on screen plays an important role in several episodes of La Nouvelle Justine, but always only to be, in the end, thwarted, literally destroyed.

For the virtuous gaze exposed to the screen of representation, what is given to see is not tableau, but scène, and the word scène carries scandal and condemnation:

"The scene is long... scandalous, full of episodes... intermingled with lust and filth well done to scandalize that which still groans of outrages more or less similar." (P. 468.)

Justine, barely recovered from the rape of Saint-Florent, overhears from behind a copse the coupling of Bressac and his servant Jasmin. Seeing without being seen a scene destined to be unseen (Bressac, at this stage of the story, is still trying to escape his mother's gaze), Justine seems to be fulfilling the classic scenic device here. She surprises the unspeakable by chance and by breaking and entering, as if in reparation for her own rape, which she did not witness. The sexual thing that cannot be represented to her is delivered to her in spite of everything through the sleight-of-hand of the stage device, just as the brutal reality of Mme de Clèves' unseemly desire was delivered to the Duc de Nemours through the gaze trap of the Coulommiers hunting lodge.

We shouldn't be fooled by this resemblance, however: the sadistic virtuous voyeur is a priori neither the subject nor the object of desire; he doesn't find in the scene that reveals itself to him the encounter with what in spite of himself he has come to seek. The virtuous sadistic voyeur is caught up in what is repugnant to him, forcibly included in a game of desire that is foreign to him. Bressac's scene with Jasmin is characteristic of this radical strangeness: Sade shows Justine a sodomy between two men, i.e. a sexual scenario in which she cannot find a place, a scenario that in relation to her is displaced.

.The challenge from then on will be, once this screen has been set, to reduce it, to precipitate this spectator in spite of himself into the heart of this scenic space that taunts him with its radical strangeness.

Bressac orders Justine's quartering at the scene of the sodomy: the spectator's body is not only included in the scenic space, but stretched, horribly identified with this space, in order to undo in the most brutal and definitive way the screen that the stage had temporarily established at its very edge.

A second episode places Justine in a voyeuristic position, when in the boarding school where the surgeon Rodin has given her hospitality, thanks to the complicity of his daughter Rosalie, she spies on her host's outbursts:

"It was important for Justine to know the morals of the new character who was offering her an asylum; she sensed this; and, not wanting to neglect anything that might reveal them to her, she follows in the footsteps of Rosalie, who places her near a partition that is poorly joined enough to leave, between the boards that form it, sufficient daylight to distinguish and hear everything that is said and done in the next room." (P. 524.)

Justine thus witnesses several scenes of libertinage. But the virtuous screen is gradually threatened. First Rodin entrusts Justine with the key to the "magic cabinet" where his defecation becomes a spectacle for him, unbeknownst to the young girl (p. 548). Then, creating a trapdoor under Justine's bed, he takes advantage of a warm night when she has gone to bed naked to make the bed fall in the middle of his debauched cabinet (p. 550), parodying a seduction stratagem already encountered in Marguerite de Navarre4.

Certainly, the two trapdoors satisfy Rodin's voyeuristic appetite, but they indicate a spectacle without constituting, without circumscribing the developed representation of a scene. Spying on Justine's backside in the lavatory is a repeated pleasure of the libertine: Delmonse, then Saint-Florent before her rape had taken advantage5.

Without making a scene, it's more a question of turning the scenic screen upside down, of enjoying a perverted, reversed use of the veil of modesty, thus bringing back, as it were, this impossible gaze of the virtuous voyeur to the gaze of the libertine.

Always, the partition must give way: witness the trapdoor under Justine's bed, which precipitates the preserved space of the virtuous bedroom into the heart of the cabinet of debauchery.

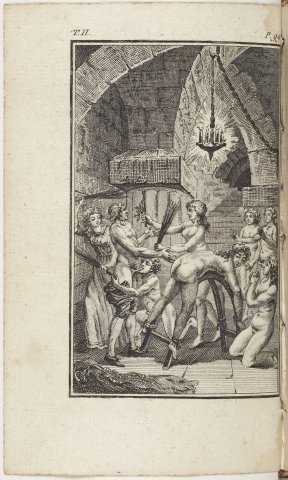

Justine at Rodin's (Nouvelle Justine, 1799, chapter 6, figure 8). Rosalie has placed Justine "near a partition poorly enough joined to leave, between the boards that form it, sufficient daylight to distinguish and hear everything that is said and done in the next room" (p. 524). She then sees how Rodin's sister Célestine brings a little girl, Agnès, to her brother and pulls the cord that holds her skirts up. Against the partition, the rods soak in a tub of vinegar water to be more scathing.

In the story of Jérôme, which Sade interposes at the heart of the episode at the Sainte-Marie-des-bois monastery, Jérôme, tutor to the Moldane children, persuades Sulpice to seduce his sister and observes their rendezvous on the sly:

"The appointments took place in a cabinet near my room so that by means of an opening in the partition I could discern the details." (P. 717.)

Here again it's the libertine who constructs the screen device to enjoy an incest scene if not virtuous, at least almost still innocent. But this scene is only fleetingly delivered to us. It is only the preliminary to the narrative process that will precipitate the two young men first into the hands of Jérôme, then above all into their father's lust cabinet: it is there that the sa dienne scene erupts, as evidenced by the engraver's choice of illustration.

However, the screen is increasingly clearly eroticized:

"My vit was in such a state, that he knocked alone against the partition, as if to mark the despair in which he was put by the dikes opposed to his desires" (p. 717).

The partition of the fourth scenic wall is identified with the obstacle that flesh opposes to penetration. Piercing the partition is a prelude to piercing the flesh. Jérôme soon leads Moldane, the father he assumes to be virtuous, to the eye he has built into the wall of his bedroom, hoping to enjoy the father's horror at the spectacle of his children's corruption. But Moldane is a libertine, which precipitates the sexualization and hence the reduction of the screen:

"I satisfied Moldane; I placed him in the hole I'd made for myself, making him believe I'd just practiced it for him: the bawd gets in while I'm screwing him." (P. 721.)

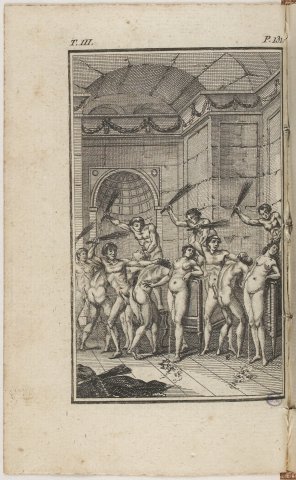

Figure 2: Séraphine makes the partition give way (Nouvelle Justine, 1799, chapter 18, figure 35). Young de L'Aigle and his sister Séraphine watch their parents' debaucheries from behind a partition. As de l'Aigle sodomizes his sister, the partition gives way, shattering the table with its food and, beneath it, Martine's head, which she lays bleeding.

Moldane is the hole, the term (which will become "cleft", p. 726) bawdily lending itself to the identification and fusion of the body caught in the sexual act and the scenic frame of the performance device. But the device fails again, as the horrifying effect (the tragic "fovbo"?) is missed. Jérôme then leads the virtuous Mme de Moldane to the same hole:

"I engage, a few days later, M. de Moldane to set the scene in his children's room; I place his wife in the hole that had served me, that had served Moldane himself; and this unfortunate woman could incessantly convince herself of all the truths I had told her." (P. 725.)

But the mother, too weak to face the vision, far from undertaking the punishment, turns away and shyly confesses that she wishes she had ignored these horrors. Jérôme then passes into the chamber of pleasures, betrays Mme de Moldane and precipitates her doom:

"Moldane, furious, rushes to the partition, breaks it down, throws himself on his wife, drags her to the middle of the room, and, before the eyes of her children, thrusts twenty stabs into her heart." (P. 726.)

It's the same verb enfoncer that, two lines apart, marks the annihilation of the screen and the virtuous voyeur, identifying the partition device with the martyred body of the innocent mother. The reduction of the screen has to do with the reduction of the female body, which, as it happens, constitutes the fundamental stake of the Sadian scene.

At the end of the book, the Histoire de Séraphine, interspersed by Sade with the episode in which Justine is sequestered in the brigands' cave on the outskirts of Lyon, offers a variation on the same device. Séraphine's brother, the young de L'Aigle, offers his sister the chance to spy on their parents' orgies from a nearby room. Knowing against knowing, Séraphine discovers the secret of her parents' debaucheries at the same time as her younger brother makes her lose her virginity. It's a question of "pressing our eyes against the slits in a partition, which separated the room where we were from the one where the orgies were to be celebrated." (P. 991.) Just as Jerome had only left his hole to sodomize Moldane, de L'Aigle takes Seraphine from behind:

"Often de L'Aigle had left the role of spectator to fulfill that of agent; and, as the position I was in made it rather difficult for him to enjoy my front, the little libertine compensated himself from behind." (P. 995.)

There is thus, each time, a reversal, via the orifice, from the ocular discovery of sex to the anal experience of sex. The partition separates, as it were, these two paths, these two screen devices (optical and carnal), then, by giving way, reduces them to a single one.

This time, the partition gives way of its own accord:

"Greatly heated by what I saw, I leaned heavily on the partition, presenting, as best I could my bottom to de L'Aigle... But, Grand Dieu! what an event! The board, badly secured, came loose, and was about to fall on Martine's head" (p. 996).

The two young voyeurs thus find themselves right in the center of the salle des plaisirs, crushing, bloodying one of the girls employed there. The reduction of the partition involves the crushing of the female body, crushing to the point of indifferentiation of blood and semen, anal and genital, masculine and feminine, since it is a young couple who take the place of the crushed woman.

The screen of the partition thus fails to circumscribe the uncircumscribed of the scene. The screen must give way just as flesh must give way under the pressure of sex. But above all, this annihilation of the screen thwarts the division of the performance space into vague space and restricted space. On the other hand, and superimposed on this geometrical schize of the scenic space that Sadian writing refuses and reduces, the partition is identified, in the woman's body, with the edge of genital and anal, which the Sadian scene will strive to break, to reduce, to bring back to the indifferentiation of the cloaca.

On two occasions, Justine is compared to an eel: faced with the "ferocious Dubourg", "lighter than an eel, Justine avoids everything" (p. 427); to escape Rodin, "light and supple as an eel, she slips away, escapes the arm that holds her" (p. 551). Wladimir Granoff has shown how the dissection of eels, with which Freud began his scientific career, led him to place the cloaca, the site of sexual indifferentiation, at the center of his thinking on sexuality, and the fragile membranes from which, quite precariously, something of the genital order is circumscribed6. Justine is the site of sexual indifferentiation, or at least that's what the Sadian scene sets out to reduce her to.

The device of the partition, which we've shown Sadian writing strives by all the means of perversion to prevent from functioning as a scenic device, thus seems to articulate something other than the stage, something that would precisely have to do with one or more sexual norms and, from there, with one or more discourses on morality.

II. The two paths of discourse and their scenic articulation

If the differential system that regulates the unfolding and meaning of the Sadian scene is not essentially based on a schize of scenic space, the play of the partition reveals another, fundamental separation between two paths, the anal and the genital. In Sade's work, there is a scandal of the female body, which Bressac sums up with a lapidary exclamation, showing Justine to Jasmin:

"See, see this pierced belly... see this infamous cunt; here is the temple where absurdity sacrifices; here is the workshop of human generation." (P. 471.)

It's not essentially a question here of homosexuality, which is just one of the many declensions of the sadian libertine's perversion, but rather of the genital way, considered by the sadian libertine, even heterosexual, as an unbearable feminine supplement. Sade's woman is not barred by the lack of phallus, but on the contrary endowed with a genital supplement, which the scene aims to reduce to anal indifferentiation. The rear of the woman's body is the sadistic norm, which the front disrupts in the scene, until this supplement is reduced by the torture. This device is carried by the two confronting discourses of virtue and vice, of Justine and the libertine.

The discourse of virtue is a discourse of the veil: it dresses the body, it inscribes it in a social bond, it wraps itself in the hymen7, i.e. both the symbolic sanction of marriage and the membrane that preserves virginity.

In contrast, the discourse of the libertine is a discourse of the partition: denuding, manhandling the victim's body, he reveals the compartmentalization of the two anal and genital tracts; he undoes and denounces the social bond, advocating "isolism", systematically profaning all bonds of kinship, recognition, reverence. Sadian isolationism is an isolation of the individual. Finally, the praise of anal penetration erects compartmentalization as a principle of jouissance: not having to tear any membranes, the penis avoids the veil and the bond to enjoy the narrowness of a receptacle that its compartmentalization reduces.

There is therefore a kind of superposition and concordance between the two discourses of vice and virtue and the two sexual pathways, the anal and the genital, with this superposition organizing a play of veil and partition.

The unfolding of the discourse is identified with the path of the way. The track is omnipresent in the text, and first and foremost as a road. Justine travels the roads: "Il fut question de se remettre en route" (p. 440).

To the material road of the narrative journey corresponds the metaphorical road of symbolic choice. From the outset, the novelist proclaims his intention to "acquaint this unfortunate bipedal individual with the way in which he must walk in the thorny career of life" (p. 395). He intends to expose "the striking examples of happiness and prosperity that almost inevitably accompany [libertines] in the overrun road they choose" (p. 396). Rodin, at his boarding school, keeps a few students out of his circle of debauchery: "It takes some," Rosalie replied, "to maintain the calm he wants to enjoy in the midst of the storms that must necessarily rise ceaselessly on the atmosphere of a similar road." (P. 532.) Faced with this road of vice, Sade camps that of virtue: "Mme de Bressac did everything to bring her son back to the paths of virtue" (p. 475).

What we call here the path of discourse thus superimposes the theoretical development of a philosophical system, the choice of a sexual path and the unfolding of a narrative journey. Here we touch on the central device of the Sadian novel, illustrated by the frontispiece.

Annibal Carracci, The Choosing of Hercules, oil on canvas, 1595, Naples, National Gallery of Capodimonte

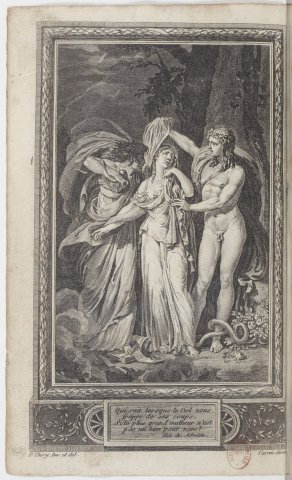

Since the frontispiece of Justine, Sade had chosen to allegorize his novel with a perverted representation of the choice of Hercules. We know the allegory of Prodicos, which tells how young Hercules at the crossroads stopped for a moment, having to choose between the laughing, easy path of vice, which led to a precipice, and the arid, thorny path of virtue. Erwin Panofsky, who has studied representations of this allegory in detail from late antiquity to the Enlightenment8, has shown how, starting with Philostratus' ekphrasis, in the Life of Apollonius of Tyana, the representation of the two ways is identified with that of two women, then how, under the influence of the Judgment of Paris, whose theme is very close, these two women were represented under the features of Venus and Minerva respectively.

The choice of the two paths does form the basis of the novel, but Sade is not content to simply reverse the right and wrong choices. At stake is the reduction of both paths to a single one, just as the Sadian torture must reduce both sexual paths to a single one.

Frontispiece to Justine, Paris, Girouard, 1791

In the frontispiece to Justine, Virtue (or Justine) is placed between Lust and Irreligion, hardly a choice, though the iconographic device is one of choice. With her right hand, Justine pushes aside Irreligion and turns towards Lust, while looking to the heavens for help. The choice of the lustful Apollo is the choice of the genital way and of love, which Justine always attempts in the face of the libertine, with whom she repeatedly falls more or less explicitly in love:

"Whatever Bressac's unworthy ways were for her, from the first day she had seen him, it had been impossible for her to defend herself from a violent movement of tenderness for him; gratitude increased in her heart this involuntary inclination, to which the perpetual frequentation of the cherished object lent new strength every day; and definitely poor Justine adored this scoundrel in spite of herself, with the same ardor as she idolized her God, her religion... virtue. " (P. 475.)

It's the same movement that precipitates Justine in Lyon to Saint-Florent, who has nevertheless robbed and raped her:

"If this man, she thought, had no good intentions, would it be likely that he would write to her in this way?" (P. 957.)

Hadn't she thrown herself into his arms after their escape from Coeur-de-Fer's?

"Justine, moved, threw herself into Saint-Florent's arms. "Oh, my uncle," she tells him tearfully, "how sensitive your soul is, and how much mine responds to it!..." (P. 464.)

The narrative device, by identifying the choice of virtue with the choice of the genital way, necessarily precipitates Justine towards the libertine who materially turns her body as, symbolically, he turns virtue into vice.

The triptych offered by the frontispiece is that of the Virgin, the tribad and the libertine, the fundamental components of the Sadian scene, and at the same time it represents the confrontation of the two discourses of Virtue at the center and Vice on either side of it. Finally, it relies on the device of choice, where Vice and Virtue vie for the central, still uncertain character. These three levels of meaning - scenic, allegorical and semiological - are imperfectly superimposed, thus offering an outlet for the play of sadistic perversion.

.Frontispiece for La Nouvelle Justine ou Les Malheurs de la Vertu suivie de l'histoire de Juliette, sa sœur. Ouvrage orné d'un frontispice et de cent sujets gravés avec soin, [Paris, Colnet du Ravel,] 1797 [1799], cote Bnf Enfer2511

The frontispiece to La Nouvelle Justine, which actually opens and allegorizes the set formed by La Nouvelle Justine and the Histoire de Juliette, more explicitly reverses the choice of Hercules. While Justine on the left is precipitated by the demon of lust into the brambles and abysses of virtue, Juliette on the right soars toward the temple of Glory, accompanied by Amour, figured as a putto bearing roses, and Psyché, recognizable by her butterfly wings. In the center, Themis, goddess of Justice, signifies with her arms on the left the lowering of Justine, on the right the raising of Juliette.

Themis is helmeted in the manner of the Minerva of Hercules' choice, while Venus, absent, has delegated the couple formed by Psyche and Amour, who lead Juliette, to represent her. Venus and Minerva, sexual pleasure and wisdom, are thus no longer opposed, but reunited on the upward path, which becomes both the path of vice and the path of flowers.

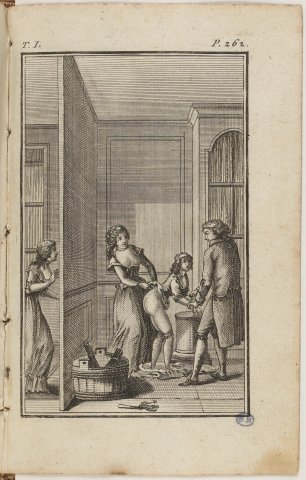

Fustigation at Sainte-Marie-Des-Bois (Nouvelle Justine, 1799, chapter 8, figure 13). The monks have decided to put an eighteen-year-old girl to death. They tie her to the "infernal machine". Each monk must take his turn fustigating her; "another girl, taken from the strongest class, whips the monk while he operates; and one of the young boys, kneeling before him, sucks him. The one who is to succeed the whipped one, is forced to remain on her knees, hands clasped, in the attitude of pain and humiliation; well in front of the whipper, she asks him for mercy, she implores him, she cries" (p. 618).

Such an insistence on perverting the device of Hercules' choice marks that this is no mere play on the novel's moral alibi, an alibi incidentally quite flayed in La Nouvelle Justine. Something deeper is at stake in this choice, which we have shown to cover a choice of the sexual path.

Fustigation and excrement (Nouvelle Justine, 1799, chapter 12, figure 24). Sainte-Marie-des-Bois convent episode. As the monks whip young boys and girls arranged alternately, the former are forced to defecate, the latter to urinate.

At the articulation of the scene and Sadian discourses, we find this mystery of the doubling of woman with which Hercules is confronted: woman is Venus and Minerva, Vice and Virtue, Juliette and Justine, profane Love and sacred Love, private space of intimate enjoyment and public space of festive celebration, at the two poles of the hymen.

E. Panofsky notes, as we have said, that the extraordinary development of the iconography of the Choice of Hercules from the seventeenth century onwards corresponds with the attraction of another scene, that of the Judgment of Paris. This attraction poses a problem of representation that is also, for Sade, a problem of path: there is room for only two women in Hercules' Choice, and Juno is ousted; likewise the third sexual path, the oral path, is pushed back by Sade to the periphery of foreplay and seems unlikely to play any essential role.

Or this third way, the way of Juno, could well constitute, in the Sadian universe, the carefully concealed dimension of the unrepresentable. Between the figure of the innocent and that of the tribade, Sade rarely evokes that of the mother, of Juno. In this respect, Mme de Bressac is an exceptional representation. The mother is the initiator of sexual play, the gateway to a woman's desire, as evidenced by Bressac's humiliation of his mother, his first wife. The mother is the space of the sadistic scene: it is here that Mme de Moldane dies and is desecrated. The mother also represents the interdict of the anal way and, for this reason, must be eliminated: the genital supplement that makes the female body scandalous makes the woman a potential mother and carries, right to the heart of the sadistic scene, the interdict of her consumption, which must be turned upside down, destroyed in order to accomplish the profanation.

On the other hand, orality, under the anodyne guise of sexual foreplay, covers the orality of prayer, as strikingly illustrated by engraved subject no. 13, depicting a fustigation scene at Sainte-Marie-des-bois. The fellatio on the left and the supplication on the right proceed from the same gesture, the same attitude. The text evokes the two actions in two successive sentences, whose constructions invite comparison9.

Orality constitutes the body of the virtuous innocent as an interface between the discourse of vice and the discourse of virtue: it utters prayer and prepares lust. It is the archaic base from which the choice, the feminine splitting, is prepared. Justine's body is compared by the libertine to the temple of Venus, with its two altars. Justine's words, her voice, lead to both sexual paths.

We have identified the narrative device that regulates the unfolding of the whole of La Nouvelle Justine and articulates scene and discourse around the perversion of Hercules' choice. What remains to be examined is the meaning and stakes of such a device.

III. The stakes of Hercules' choice, or the denial of sexuality

We might consider La Nouvelle Justine as a Justine story; the title of the second part of the diptych invites us to do so. The episodes unfold as a sexual journey and, perhaps less horrifyingly than it may seem, a process of maturation and elaboration of the female "self".

Because, and this is what makes this novel so interesting from a psychoanalytical point of view, the subject is female. It's hardly surprising, then, that the castration complex is not represented: we know the difficulties Freud, and later Lacan, encountered in involving the female subject, a necessary condition for the establishment of Oedipus as a universal paradigm for the structuring of the "self". Yet in the panoply of Sadian horrors, castration plays no role.

What if this absence was not, or was only secondarily, the effect of Sade's perversion? What if it was part of this choice of the female subject, a literary choice and intellectual bias first and foremost, before coming under the heading of unconscious intention directed by perversion? If the choice of the female subject constituted, in the greatest tradition of the Enlightenment, against the Oedipus and its cuts, and its limits, the choice of the universal?

In the sexual journey recounted to us, Saint-Florent's rape constitutes a traumatic anchor point: this scene, which Justine exceptionally does not see because she is unconscious, could well constitute the original scene10 that all the others merely repeat and cover up or displace, playing, precisely through the condensation of horror, the role of screen scenes.

Or the rape of Saint-Florent corresponds for Justine to the experience of the second way, the genital way, which we've shown is also the way of virtue. The Sadian novel can therefore be analyzed as a novel of the denial of genitality. The development of the libertine's discourse compensates for, supplements not the failure, but the indefinite postponement of the advent to genital sexuality.

The world of the sadistic scene is therefore the perverse world of the pre-genital or non-genital organization of sexuality. In this world, the woman carries the phallus: not only does the tribad ejaculate and even proceed to penetrate, but she holds, through her discourse as initiator, the knowledge of the phallus.

It may seem paradoxical to define the Sadian novel as a novel of the denial of genitality when genital sexual penetration is so often said, shown, repeated in it. The genital way is practiced, certainly, but as a profanation; unlike the anal way, it is never celebrated and never becomes the chosen way.

It may also seem strange to identify the libertine's speech with the mother's speech: certainly Delmonse and especially Dubois are famous initiatrices; but so many libertine men spout their speeches to Justine! Cœur-de-Fer, Bressac, Rodin, Saint-Florent, to name but a few. It is through its content that libertine discourse originates as a discourse of the mother, of mother nature first and foremost, which it summons against the chimeras of religion and the social contract, and more generally as a discourse of the abject, i.e. refusal of the object relation11 and exaltation of horror, which constitute the archaic universe of the "self" placed in the maternal sphere, before separation, the symbolic cut.

In the face of libertine discourse, however, the discourse of Virtue is neither the discourse of the master (there can only be such in Sade's debauchery), nor of the father, but, as we have seen, the discourse of Juno. Justine's God is contaminated by the images with which the libertine associates him: he is "a chimera", a horrifying figure of the archaic mother, a mother profaned by defecation, by anality. He is also a "ghost", whose proximity to the mother Jean-Pierre Dubost has shown to be experienced as a sublime apparition, as a Virgin, as a consoling and exposed Laure, enveloping, repairing, and offered to tearing12. As for the temples and altars where Justine claims to come to prostrate herself, they are brought back by the libertine to the temple of Venus, i.e. Justine's body. So, in the elaboration of Sadian thought, in the interplay of its double discourse, we never leave the female body.

The Sadian denial of sexuality (the text stages sex, but refuses the advent to a sexuality) cannot therefore be identified with the psychoanalytic schemas of perversion: avoidance of the castration complex, refusal of otherness, uncertain, if any, relationship to the symbolic taken in its Lacanian sense.

Sade on the contrary makes a system and even a double system. Profaning the mother, he establishes the discourse of the libertine. Profaning the virgin, the little girl, he extracts from her mouth the discourse of virtue. The Sadian scene is a formidable machine for producing the symbolic. What's more, thanks to the exhibitionist perversion that animates it, it reveals the production of the symbolic, which is usually masked and invisible: the production not of a system of values, an order of law, but of two contradictory orders, two registers confronted in perpetual antagonism. The symbolic principle, the principle of libertine revolt, is opposed by the symbolic institution, the socialized discourse of virtue, a screen discourse, which covers the other and, in fact, proceeds from it.

For

"Who knows, when Heaven strikes us with its blows,

If the greatest misfortune is not good for us13!"

The quotation placed by Sade in the cartouche of the engraving that serves as the frontispiece to Justine institutes "the remedy in evil"14 as the central dialectic of symbolic regulation.

But above all, it reverses and hijacks the Oedipal device. In fact, Sade takes this quotation from a tragedy by Ducis, Œdipe chez Admète. The play condenses and blends Sophocles' Œdipe à Colonne and Euripides' Alcestis. Act III "represents a dreadful desert. In the background we see the Temple of the Eumenides, & on the side yews, cypresses, & rocks". As the human sacrifice is being prepared to appease the terrible Erinyes, all the protagonists of the drama converge on the temple. In Scene 1, Polynices alone hears the arrival of Antigone and Oedipus, whose forgiveness and support he would like to enlist in his war against Eteocles. Intimidated, however, he hides. Scene 2 consists of a dialogue between Antigone and Oedipus. Oedipus' arrival at the Temple of the Eumenides is modeled on the beginning of Oedipus at the Column. Oedipus remembers all his crimes and asks the goddesses to provide him with a tomb. To Antigone, who protests against the injustice of fate ("How could such just Heaven deliver you / To the pains whose excess has just torn you apart!"), Oedipus then responds with the verses that Sade quotes, signifying that misfortune can be turned into good: this is what the play is all about. Oedipus, by sacrificing himself to the Erinyes, spares Alcestis and Admetus the death to which one or the other was condemned, and redeems himself in the eyes of men.

Beyond the playwright's laborious exercise in rhetorical synthesis in the scholastic tradition of Jesuit imitatio, Ducis's entire play is populated by ghosts: from the very first scene of Act I, Admete tells Polynices how Tysiphone appeared to his father, pronouncing the curse that foretold the impending necessity of human sacrifice.

"Tisiphone, emerging from the infernal sojourn,

Came to answer herself, and made the day pale.

At her awful aspect the altars shook,

With a sweat of blood the marbles dripped,

Our incense was extinguished, or no longer dared to rise:

A dull fury seemed to torment her:

But no sooner was she about to spill out,

When we saw all her serpens rise up to hear her." (I, 1.)

The curse signified to the father is redoubled in scene 3 by the account of Alceste, his daughter-in-law, who tells Admète about the nightmare she has just had.

"In that time of night when darker vapors

Redouble the sleep, thicken the shadows,

My father's passing (oh heaven! can I think of it!)

To my trembling spirits came to retrace." (I, 3.)

Alcestis relived in a dream the death of his father Æson, scalded and stabbed at Medea's instigation by his overgullible sisters, who believed this would restore his youth. But this death was only a sign of the death foretold for Alceste, her husband.

"Beneath your footsteps just now the Tenare opened up,

An invisible hand was dragging you to Tartarus;

You cried out: farewell. I shuddered, I ran.

Then our children appeared between us;

They raised their tender voices to us;

They chained your feet with their innocent hands.

Suddenly, a dreadful thunderbolt sounded.

Then everything calmed down, everything vanished;

Of these diverse objects the frightening assemblage

Of your perils above all still leaves me the image;

And, should this vengeful sky irritate my troubles,

Whether it's Admète's father, Æson being tortured by his daughters, Admète himself, depicted dying in front of his children, or, at the end, in the fifth act, Oedipus being sacrificed in front of Antigone, Eteocles and Polynices, it is indeed the death of the father that is obsessively staged.

This death of the father, framed by the maternal ghosts of Tisiphone and Medea, the holders of tragic knowledge, would constitute, as it were, the phantasmatic underpinning of the Sadian device. The horror that seizes Antigone and Alceste at the death of their father becomes Justine's horror at the sexual torment in which paternal law is desecrated. Doesn't Sade internalize a very feminine horror of the sexual act, fantasized as a killing (the Sadian torture), as the reduction of the double (the destruction of the partition) and as the revelation of the mother's knowledge?

.Notes

La Scène, littérature et arts visuels, texts collected by Marie-Thérèse Mathet, L'Harmattan, 2001 and Stéphane Lojkine, La Scène de roman, A. Colin, 2002.

References to Sade are given in the edition compiled by Michel Delon, Gallimard, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, 1995.

L'Écran de la représentation, dir. S. Lojkine, L'Harmattan, Collection " Champs visuels ", 2001.

Marguerite de Navarre, L'Heptaméron, "Première journée, Quatriesme nouvelle", Classiques Garnier, 1967, pp. 29-30. The gentleman climbs through a trapdoor in his room to the princess's bed in the room above, in an attempt to rape her.

See p. 464, "À cette petite scène près..."

Wladimir Granoff, La Pensée et le féminin, Minuit, "Arguments", 1976. See in particular "Le modèle de la dissection et la pensée du féminin", pp. 164-185.

See "Representing Julie: the curtain, the veil, the screen", in L'Écran de la représentation, dir. Stéphane Lojkine, L'Harmattan, "Champs visuels", 2001.

Erwin Panofsky, Hercules at the Crossroads, 1930, French trans. by Danièle Cohn, Flammarion, "Idées et recherches", 1999.

See p. 618.

Freud, "L'Homme aux loups", Cinq psychanalyses, French trans. M. Bonaparte and R. M. Lœwenstein, PUF, 1954.

See Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror, "Approach to Abjection", Seuil, 1980, Points-Seuil.

Jean-Pierre Dubost, "Les fantômes de Sade", in Paradox oder über die Kunst, anders zu denken, Mélanges für Gerhart Schröder, quantum books, Kemnat 2001, p. 142-175.

Œdipe chez Admète, tragédie, par M. Ducis, secrétaire ordinaire de Monsieur, l'un des quarante de l'Académie françoise. Représentée, pour la première fois, par les Comédiens François ordinaires du Roi, le Vendredi 4 Décembre 1778. A Paris, chez P. Fr. Gueffier, Libraire-Imprimeur, au bas de la rue de la Harpe, à la Liberté. M.DCC.LXXX. (approved by Suard on Dec. 3, 1778). Bibliothèque de l'École normale supérieure, shelf mark Ulm LFq118 8°. Act III, end of scene 2.

Jean Starobinski, Le Remède dans le mal, Gallimard, "Nrf Essais", 1989. Jean Starobinski shows how the very idea and expression run through the whole of Rousseau's work.

Fiction, illustration, peinture

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Fiction, illustration, peinture

La scène de roman

La scène de roman : introduction

Renaud dans le jardin d’Armide

Rastignac chez Mme de Restaud

Gilberte derrière les aubépines

La poignée de porte de tante Berthe

La double aporie du topos

Illustrer la fiction

Molière, une parole débordée

Marillier, l’appel du mièvre

On n'y voit rien

Illustrations de l'utopie au XVIIIe siècle

Le temps des images

Du conte au roman graphique

Déconstruire l’illustration

Régimes de la représentation dans la gravure d’illustration classique

Penser la fiction depuis la peinture

Une sémiologie du décalage : Loth à la scène

Introduction à la scène comme dispositif : Paolo et Francesca

La main tendue, le regard démasqué

De Silène molesté à la chair blanche des nymphes

Chambres de la représentation

L'intimité de Gertrude

Brutalités invisibles

Parodie et pastiche de Poe et de Conan Doyle dans Le Mystère de la chambre jaune de Gaston Leroux

Le dispositif de la chambre double dans Les Démons de Dostoïevski

Scène pour voir et chambre des brutalités

La Princesse de Clèves

L’invention de la scène dans le roman français

La canne des Indes

L'aveu

La princesse, la religieuse et l'idiot

Richardson

Entre scandale et leurre

Introduction aux Lettres angloises, ou histoire de miss Clarisse Harlove, par Samuel Richardson

![Frontispiece to <i>La Nouvelle Justine ou Les Malheurs de la Vertu suivie de l'histoire de Juliette, sa sœur</i>. Ouvrage orné d'un frontispice et de cent sujets gravés avec soin, [Paris, Colnet du Ravel,] 1797 [1799], cote Bnf Enfer2511](/system/files/styles/large/private/notices/001/haute_def/001619.jpg?itok=U-MiZ-_f)