The map as a denial of utopia

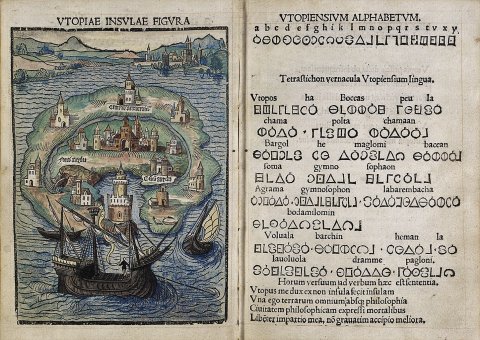

Utopia is first and foremost a geography. The first utopian image, that of the frontispiece engraving of the first edition of More's L'Utopie , in Louvain in 15161, is an anonymous woodcut depicting the island of Utopia, organized, in accordance with More's description, as an immense port. The island is not lost in an empty ocean in the immediate background, we can make out the mainland, its towns and villages. Ahead, boats pass each other at the harbour entrance. The island is an interface for exchange and communication. In 1595, the famous Antwerp cartographer Abraham Ortelius produced a detailed map of the island of Utopia2. A friend and emulator of Mercator, author in 1570 of a sumptuous Theatrum orbis terrarum that would be the atlas of Europe for half a century, Ortelius' map places Utopia in the realm of real geography: the island, moreover, loses the symbolic crescent shape indicated by Raphael Hythlodeus' description, taking on the irregular, jagged shape of a real shoreline that the cartographer would have meticulously rendered from de visu observation. The cartographic artefact brings it into the game of the visionary and the visual : the narrative singularizes it, makes it emerge as a singularity in representation ; but observation (or the simulacrum of observation that takes its place) authenticates and normalizes it, inscribes it in a cartographic norm ; such as the Isole piu famose del mondo by Thomaso Porcacchi3, published in Venice in 1572, reissued and expanded until the early 17th century : the author of the maps, Girolamo Porro, was also the first copperplate illustrator of the Roland furieux, for the Franceschi edition of 15844. Here, cartography plays a decisive standardizing role for fictional illustration.

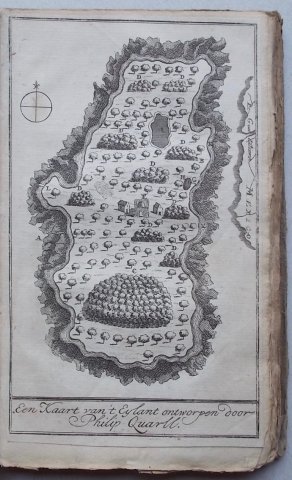

The island of Philippe Quarll, the hero of Dorrington's English Solitaire, on the frontispiece engraving of the original 1727 edition reprinted in 17295, obeys in some ways always the same principle of representation : on the one hand, the near-symmetry of the groves of trees occupying the surface of the island, its almost rectangular shape saturating the space of the page, order an unreal symbolic space reminiscent of the carte de Tendre6 on the other, the jagged rocks that bar access to the shoreline, and the nearby presence of the mainland and its real place names on the right, integrate the utopian island into the cartographic space of travel and the relationship of things seen.

With Swift, this tension takes on a disquieting form. In the original edition of Gulliver's Travels, in 1726, on the white rectangle of an almost empty engraving, floats the precise, concentrated, bristling with names, cutout of one or rather two islands, Lilliput and its neighboring Blesuscu, or the almost-island of Brobdingnag, brazenly, ironically clinging to North America, or Balnibari with Luggnagg, or finally Balnibari with the flying territory of Laputa, and its trajectory of regular segments, cleverly notated in dotted lines7. Unlike the single island of Utopia, which in More's early editions allegorically drew a face in the manner of Arcimboldo, i.e. the signifying totality of a figure, Swift's island pairs are pairs of authentication : the real continent authenticates the imaginary almost-island ; the marine island - the flying island. In Voyages de Glantzby dans les mers orientales de la Tartarie (1729), the imaginary empire of Norre or Norreos, off the coast of Japan and Tartary, is presented with unfinished outlines8 : this strange map with its discontinuous shores could display its fictional status through its blanks if contemporary maps of the world didn't then themselves sometimes present the same kind of gaps. The western contours of North America remained uncertain until the middle of the century, while the existence and course of the southern lands were the subject of all kinds of conjecture : the derealization of the white on the map operates just as well as authentication.

.

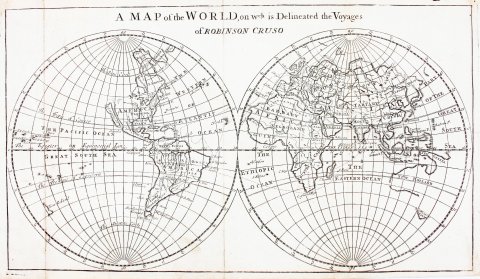

So, in the second volume of Robinson Crusoe from 1722, the world map entitled A map of the world on which is delineated the Voyages of Robinson Cruso9 places Defoe's fiction firmly within a real cartography of space, a space that the traveler's dotted path occupies, inhabits and invests, that the spindles of meridians and the lines of latitudes square and circumscribe. But this space itself is haunted by emptiness: on the left, above the Tropic of Cancer, the west coast of North America breaks off beyond a hypothetical island of California; continent and ocean are no longer separated. Similarly, on the right, on either side of the Tropic of Capricorn, the outline of New Holland remains undecided : only the western coast of what would become Australia in the 19th century was known at the time further north, New Guinea opens out into the South Sea10 further south, a mysterious Van Diemen's Land hesitates between being an island and a continent : it wasn't until the very end of the century that his circumnavigation definitively established it as the island of Tasmania.

On the map of Baron Holberg's Voyage de Nicolas Klimius au center de la terre, which is the first of three figures in both the Latin edition and the 1741 French translation, white still dominates11 : on the earth's surface, only the mountain from which Niels fell into the underworld stands out in Norway underneath, the underground sun shines down into the center of a great void in which the small ball of the planet Nazar and Niels falling towards it seem very small. The gravitational games in which Niels is whimsically engaged humorously underpin Copernican heliocentrism. If we compare the map in Nicolas Klimius's Voyage with the concentric circles in the diagram in Copernicus's De revolutionibus (1566)12, we see the same layout, without the trajectories : Copernicus' diagram fills in, blackens the image of the structure it exhibits Mentzel's map for Holberg's utopia evacuates the structure, retaining only the device. The very countries Niels visits in the underworld after his exile in the firmament of Nazar, Martinia, Mezendore, Quama, are merely names inscribed beneath the surface of the earth's crust. In the Swedish edition of 1767, the illustrator attempts to fill this void by giving them the substance of a few mountains13.

Utopia can be seen on the map, but it's a paradoxical map, drowned in white, a map that disconcerts the locator, yet authenticates itself from this vacillation of landmarks, oscillating between the invisible continent of imaginary visions and the unrecognized continents of impossible observation. Faced with Holberg's subterranean world, perhaps even more than with Swift's islands, the reader experiences this vacillation: it's a vertiginous fall and a balancing of orbits. This fall is still part of the symbolic cosmography that Dante mobilizes and that Boticelli illustrates for the Divine Comedy. The hollow mountain from which Niels falls has the shape of Purgatory, where Dante and Virgil emerge from the Underworld14. Holberg curiously reconciles the old geocentric system with the heliocentric one by placing the fictional sun at the center of the earth. The concentric interplay of spheres was originally Ptolemaic: Beatrice reminds Dante of this in Canto II of Paradise. To depict the poet's trembling at the revelation of the mysteries of the cosmos, Botticelli dissolves space in the white of the circle in which he inscribes his figures, Dante vacillating before the play of spheres that his Lady unfolds before him15. No doubt Botticelli's sketches were intended to receive color and other strokes. Nevertheless : the inscription of the two figures in a circle returns obstinately in the following drawings, right up to Canto XXIV, where it is disseminated in a concentric swirl of lights, radiating from the divine principle16.

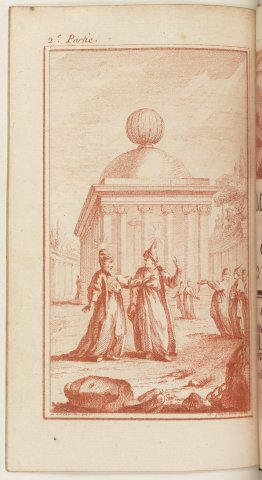

In addition to maps of islands and worlds, we should no doubt add views and plans of ideal cities, which draw more assured figures. But in the face of the descriptions of ideal cities and geometrically perfect temples favored by utopian texts, images are few and far between. In the French translation of 1753, the frontispiece of the second part of Mémoires de Gaudence de Lucques, the Temple du Soleil des Mezzoraniens17 or, in the French translation of Les Hommes volants18, the cross-shaped plan of the town of Sassdoorptswangeanti.

This is because the function of the map is not to unfold, but on the contrary to deny utopia, to reduce placeless fiction to the authentic, measurable space of travel. The blank of the map returns from this denial. It's not the map that founds and delimits the utopian genre, but its hollowing-out, or the loss of the landmarks that should ensure its legibility: the line is unraveled or lost, the articulation of utopian space to real space, in the form, for example, of the journey from the continent to the island, from the known island to the unknown island, is blurred, retracted. The narrative equivalent of this blank map is the topos of shipwreck, which pervades this literature of imaginary travel, and will be echoed in its illustration. The shipwreck breaks the course of the journey, introducing a blank in the map between departure and destination. Raphaël Hythlodée, in More, was not a shipwrecked man...

Figure and disfigurement

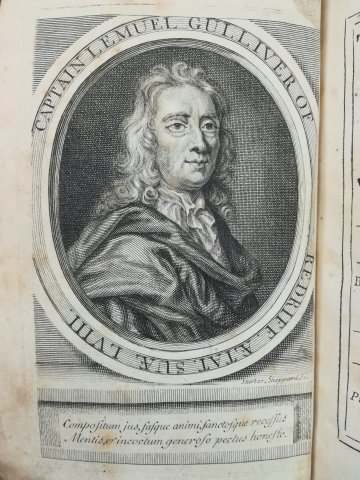

The utopia of the Enlightenment brings into play the defection of the line, and of the discursive gesture of figuration that this line accompanies and stages. If the map originally founded the line, the figure constitutes its classical assumption. The iconographic series of an illustrated edition often begins with a portrait. The original edition of Gulliver's Travels opens in 1726 with a portrait of Captain Lemuel Gulliver of Redriff ætat[is] suæ LVIII19, as if 58-year-old Gulliver were the actual author of the book : Sturt and Sheppard, who sign the engraving, may well have engraved Swift himself, who was 58 in 1725. The whole story of Gulliver's Travels can then be read as a series of successive disfigurements of this initial portrait Gulliver a giant in Lilliput, a dwarf in Brobdingnag, forgotten on the ground under Laputa, naked among the Houyhnhnms : this, at least, is how the illustrator of the first French translation, in 1727, depicted him, substituting these figures for the maps of the English edition the iconographic series was repeated the same year in Holland, and again in Paris in 1762 and 179520. Gulliver's awakening in Lilliput, hampered by tiny links, even became the book's emblematic image : the text produces, for each new voyage, the description of a new island, new inhabitants, their mores, their discourses and their controversies but the image, anticipating the future of these texts which will participate in the emergence in the nineteenth century of a children's literature that pushes back the utopian discourse under the imaginary of the voyage, declines the figures of Gulliver, that is to say, according to the very classical logic of the figure, alterations, disfigurations. The noble, auctorial portrait of Swift-Gulliver falls into oblivion in favor of these figures of destitute, off-center, humorously humiliated humanity : in the Paris edition of 1797, a portrait of " Docteur Swift "21, placed in an oval similar to that of the 1726 Gulliver, breaks the autobiographical fiction.

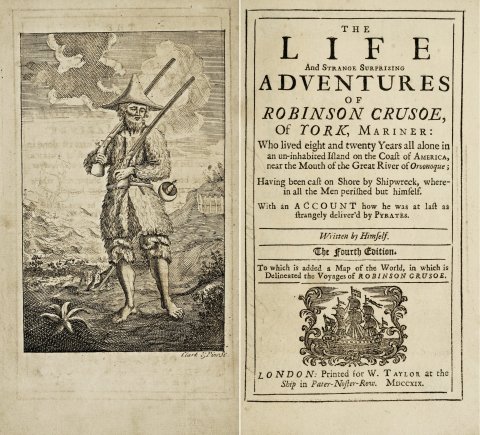

If, unlike Gulliver in Swift, Robinson Crusoe's opening portrait becomes a lasting signature of Defoe's novel, it's because it's a disfigured portrait. As with Swift, however, it is first and foremost an artefact of authorial portraiture: Defoe had taken care to stage Robinson's writing of his diary on his island. The original edition published in London in 1719 features just one frontispiece engraving22, by Clark and Pine, depicting Robinson armed with two rifles and a saber, dressed in a makeshift cone hat and animal-skin coat, camped on his island between his fortified shelter, whose palisade can be seen on the right, and his ship sinking into the waves on the left. The image was taken up, with a few variations, by Clark himself in 172223, then by Picart in the first French translation of 172024. Picart's engraving, which eliminates the shipwreck, adds a parasol and replaces the sword with a saw, then becomes the model for the anonymous engravings in later editions : the Dutch translation of the same year25, the edition published in French in Amsterdam in 1764 (" Robinson allant à la chasse "26) and the other Dutch editions that take up his iconographic program.

Robinson, bearded, shaggy, dressed like a savage and armed to the teeth, posing for the portrait, parading even, is a spectacular portrait, at once conquering and dehumanized. It is not an other portrait, a figure of otherness it is oneself, the auctorial I that the reader will be led to pronounce, to incorporate, a disfigured self, founding the utopian otherworld from its own disfiguration. The disfigurement of the figure is superimposed on the denial of utopia through the map and the portrait. Robinson's destitution is represented, in the frontispiece portrait, by an overequipment : destitute, he overabounds in ammunition exiled, he exhibits his autonomy.

.

Robinson's portrait had emulators : Philippe Quarll, Dorrington's English Solitaire, appears on the frontispiece of the 1729 edition27 shirtless, beard falling to his belly, armed with an axe and a pile of faggots : a parody of Vendredi, his monkey Beaufidelle follows him with his share of wood, a monkey man in the manner of the monkey men of Della Porta's Physiognomonie 28, whose 1586 treatise served as the basis and model for the classical theorization of the expression of passions. Beaufidelle betrays the work of animality at work in the figure of Robinson.

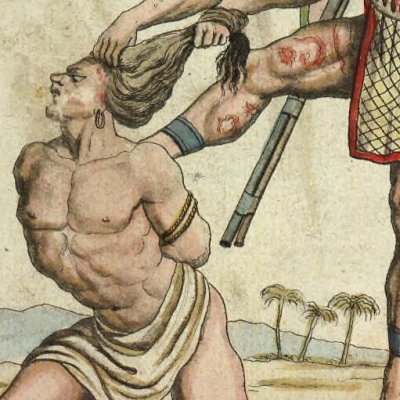

For there are, in the utopian iconography of the Enlightenment, many other animal men : the refined people of the Martinian apes in Holberg's Voyage de Nicolas Klimius29, or the ape-men of Restif's La Découverte australe30 and all their hybrid avatars from neighboring islands. In 1786, the Voyages imaginaires no longer tolerated these excesses of the classical economy of the figure. To the direct integration of animality into the figure, Marillier prefers the encounter of man and animal, exotic or monstrous : Philippe Quarll's enormous cod31, the snake slaughtered by M. de Courmelles32, the ostrich from the History of Birds33, Nicolas Klimius' griffin34, the giant eagle from L'Île inconnue killed by Chevalier des Gastines35, the alligator of the Flying Men36, the giant bird that abducts Jacques Sadeur37 are all disfigurements dissociated from the figure. In the rare representations of metamorphosis, the marvelous is hardly detectable in the image : the big dog from the Lutins de Kernosi is in fact Noble-Épine changed into a bear38 ; we can barely make out a remnant of an owl's beak on the face of Sinoüis kissing Lamékis39.

As with Swift, Defoe and Dorrington, the frontispiece of the Voyage de Nicolas Klimius is a portrait of the supposedly autobiographical traveling hero, whether in the Latin or French editions of 1741, the augmented French edition of 1753 or the Swedish translation of 1767 40 : Nicolas Klimius (Niels Klim) poses majestically as emperor of the underworld (cf. chap. XIV). Even if the serious engraving gives nothing away, the majesty of the ephemeral emperor is parodic, and Niels' story is above all the paradoxical one of a double fall: from earth to Nazar, then from Quama, in the subterranean firmament, to earth. In the luxurious Danish edition of 1789, the equivocal portrait disappears Niels is depicted in the frontispiece in his paradoxical fall, falling backwards from his earthly hole towards the subterranean sky41. The balance of utopian denial is broken, allowing in the following engravings the deployment of a continuous imaginary space, where the reader sees what the hero sees : his dream42, the spiritual retreat of the tree-men of the land of Potu43, the Potuan senators judging their late prince44 referential reality, visions and narratives reported to the narrator merge into a single imaginary continuum, of which the cave and the hole, represented as a giant eye of which Niels would be the pupil, now figure the passage45. A new figuration, of childhood and reverie, will then become possible.

The logic of disfigurement doesn't just affect the narrator from him, it unfolds in the diversity of his encounters, declined as so many variations in disfigurement. The animal is the principle of the figure the world is its becoming and its fulfillment : the singularity of the figure is inscribed within a typology, whose tableau unfolds a structure of the world.

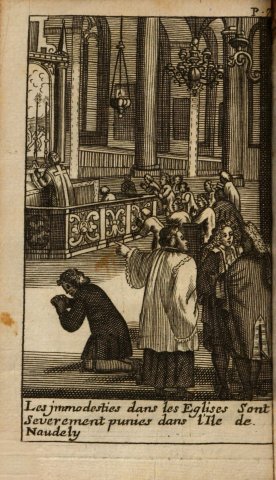

The deployment of illustration through portraits constituting a world characterizes the first trend of Enlightenment utopia. The logic of the portrait does not necessarily entail the representation of a simple figure, especially as the scenic device is already at work. In Lesconvel's highly moral Relation du voyage du prince de Montberaud dans l'île de Naudély (1703), Jacques Harrewyn's engravings seem to follow a program dictated by La Bruyère, or more precisely, reversed into a pious vow that is heavily underlined by the captions added in cartouche in the 1705 forgery : Piety in the churches46, humility of the bishops47, judges' respect for nobles48, women's modesty49 : the engravings here resemble scenes even though they are not based on any dramatized narrative event ; the moral portrait becomes a tableau and, through the series of tableaux, constitutes a world.

Les Femmes militaires by Rustaing de Saint-Jory (1735) falls into the same moral vein. The protagonist's shipwreck on the island of Manghalour enables the unfolding of a utopia that is first pastoral (the people of Manghalour descend from crusading knights stranded there in the 12th century), then oriental : the two most notable prints, drawn by Louis-Antoine Sixe, depict the clothing of Manghalour women50, spear and shield in fist, as they take part in the military effort when necessary, the other the Montagnarde with three lovers51, observed in a magic mirror by Princess Bulbul, in the embedded story that tells the origin of the Gebras. The virtuous, warlike shepherdess of Manghalour thus opposes the coquettish Montagnarde, in a moral diptych of playing cards.

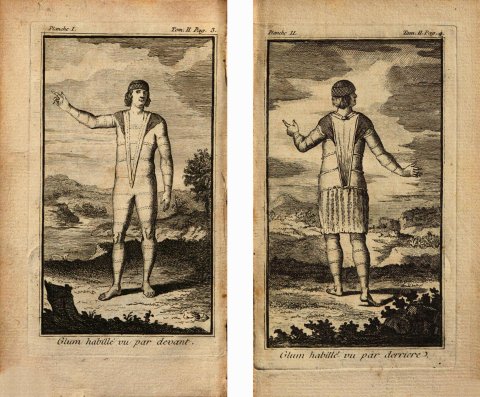

The same playing-card aesthetic is found with more whimsy in the first edition of Voyage de Nicolas Klimius (1741), after the frontispiece portrait of the narrator as an emperor and the map of the underworld. Two engravings successively depict a Potuan citizen (Typus Civis Potuani, a character, a type) and a Martinian, that is, a citizen tree and a citizen monkey52, without action or staging, like pure figures, and at the same time impossible figures : the Potuan's head and feet emerge with difficulty from the palm tree that encircles them, while the monkey in the wig, as if thrown forward, seems ready to fall back on all fours : the animal and the vegetable suck the figure towards its disfigurement. In the Southern Discovery, this aspiration proliferates : from simple night-men53 we move, from island to island, to monkey-men, bears, dogs, pigs... all the way to bird-men54.

Pokemon cards and their avatars, passionately collected by all children at the end of the 20th century, are the direct heirs of this utopian figure that was formed between plants and animals during the Enlightenment. Most Pokemons have at least two figures, the charming, harmless pet and its terrifying " evolution " the figure and its disfigurement. The figure starts from the self (the shapeless comforter, the pet) and moves towards monsters, which it identifies with the world through the collection they constitute. In Rétif, it's not Victorin, Christine and their charming children who directly observe the animal-men: they need the mediation of a utopian kingdom of happiness, and the flying machines that guarantee its inaccessibility, then its colonizing expansion. Faced with the exotic, deformed fauna they discover, above it, Rétif's illustrator Binet deploys the graceful, artificial wings of flying adventurers. The observing man is already an observed animal: the identity becomes almost perfect when the mechanical birds they have become reach the island of the bird-men. In addition to Benoît de Maillet's Telliamed, Rétif was undoubtedly inspired by Robert Paltock's Adventures of Peter Wilkins (1751), whose French translation in 1763 was illustrated : Plates I, II and IV, depicting a Glum from the front, from behind, then with his fan unfurled, still fall within the playing-card aesthetic55. Plate VI56 does, however, represent an interesting mutation : Pierre, seated on a chair and holding his rifle, watches Nasgig and General Harlokin fight in the air before him. The figures are ordered on stage, as would become systematic in Binet's compositions for La Découverte australe in 1781. But this scenic order is hampered, as it were, by the figurative constitution from which it springs: each of the combatants, surrounded by the edges of his wings, struggles to reach the other, as if the figure's autonomy were hindering the narrative relationship, while Pierre spectateur, seated on an improbable carpet, seems to belong to another world.

.

Scenic integration

The scene, its narrative tension, its representational device, is the horizon of effectiveness of Enlightenment utopia. It articulates the space of the map with the singularity of the figures, dynamically bringing their singularities into play. The stage totalizes and homogenizes the heterogeneities that make up the utopian universe. It makes utopia easily and immediately communicable, it dramatizes it, it normalizes it but, in so doing, it abdicates its discursive content, its theoretical vocation, its political ambition. Utopia becomes an imaginary journey, slipping from scholarly literature to childish entertainment.

The work of scenic standardization is noticeable from the beginning of the century. The sixteen engravings in the 1715 edition of More's L'Utopie are a significant testimony : in the 1518 edition, Holbein arranged Pierre Gilles, Thomas More, Raphaël Hythlodée and the young John Clement in the Antwerp garden where their dialogue is supposed to have taken place57 the grass bench overhanging the garden paving laid out the dialogical framework of utopia's discursive game. The first two engravings of 1715 transform this framework into a stage: More's meeting with Pierre Gilles and Raphaël Hythlodée in the collegiate church is treated in the manner of Dutch church interiors by Saenredam58, and repeats the composition by Hendrik van Steenwijk the Elder for the interior of the Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp59. In the left foreground, the secretary of the city of Antwerp, depicted as a young cavalryman carrying a sword (he was 29 in 1515, the supposed date of the interview), pulls More aside, dressed in the austere Puritan cloak, and for a moment neglects Raphaël Hythlodée, who can be seen in the background waiting between the two tombstones, recognizable by his long white beard and cape thrown over his shoulder. The engraver does not simply depict the meeting of More and Raphaël, but the complex interplay between the characters: More has seen Pierre Gilles in conversation with a stranger; Pierre Gilles has left him for a moment, takes More aside, explains to him who Raphaël is; in a third stage, after the one chosen by the illustrator, More will move towards Raphaël to invite him into his home. Pierre Gilles is positioned here between More and Raphaël Hythlodée, making a screen, and through this screen giving him to see : More can, while Gilles explains to him who Raphaël is, discreetly observe the stranger who has politely turned away.

Similarly, in the second engraving60, the grass bench on which the dialogue's interlocutors are seated is no more than a small element in the overall composition, which opens the perspective of a vast 17th-century French garden, with baroque fountain and geometrically patterned parterres : this is also the setting for Adamas and Alexis' conversations in the garden of the Château de Marcilly, in L'Astrée from 163361. The audacity of the 1715 print consists in placing the characters in the background: the animated play of their conversation (Pierre Gilles on the left, recognizable by his sword, has risen) is contrasted with the regulated play of the waters of the fountain in front of them, dominated by a statue of Neptune holding a trident, as if the order of the fountain prefigured that of utopia.

The tour de force of the following engravings consists in transposing the systematic discourse ofUtopia into scenes. The composition for Punishment of Thieves62 is ordered in three shots : in the foreground, in the shadows, the whip for those recalcitrant to community service ; in the background, in the light, the happy ploughing, in which the amending prisoners are engaged, one with a plough, another with a shovel, a third with a portcullis in the background, towards the sea, stretches the city, whose tightly drawn streets and circular shape discreetly indicate its utopian status : it could almost be any city, any landscape, that serves as a backdrop for the differential interplay of the foreground and background. The representation of the Port of Utopia, which formed the basis of the original allegorical map, is now subject to this tripartition : the illustrator assigns it a vast Dutch naval sky and a dramatic foreground, the wreckage of the Romano-Egyptian ship once stranded in Utopia63, an incident in the narrative that doesn't directly concern Raphaël, but, pinned up by the image, allows the utopian narrative to be normalized by placing at its head the shipwreck constitutive of the classic utopian voyage : the shipwreck episode, virtually systematic in Enlightenment utopia, is illustrated in Robinson Crusoe64, in Les Femmes militaires65, in L'Île inconnue66.

The scenic integration of utopian material is spectacular when we can follow the evolution of iconographic programs of the same text in its successive editions. We have seen, for example, the extraordinary fortune of the opening portrait of Robinson as an over-equipped tramp. Another episode popular with 18th-century illustrators was Robinson's mystical dream, which led to his religious conversion: he rediscovered the habit of prayer and began to read the Bible regularly. In the Dutch translation of 172067, the celestial apparition of the dream is depicted haloed in fire, on a level with Robinson, whom she threatens with her pike. In Picart's engraving for the French translation of the same year, Robinson is at his table, his Bible open before him. Above him, in a clearly circumscribed luminous oval that contrasts with the darkness of the room, the dream scene is represented as a reduced model: the dream is entrenched in an explanatory bubble, the symbolic performance of the mystical vision is circumscribed, reduced to an off-stage causality: it is in front of his open Bible that Robinson experiences conversion; reading competes with vision. In the 1764 edition68, the mandorla of the vision has disappeared, the caption states that " Robinson finds consolation in the words he has just read from the Bible " : it's after reading the Bible that, pushing the book away, he raises his head and arms to Heaven to invoke God causality has reversed, the visionary deployment is completely internalized.

In the same way, Vendredi's submission to Robinson, who has just saved his life, is described in the text as a characteristic symbolic ritual, the representation of which can be found with the Iroquois submission ritual illustrated by Grasset de Saint-Sauveur in 179669. The illustration in the Dutch translation of Robinson Crusoe scrupulously respects the ritual described by Defoe : kneeling Vendredi has folded his head to the ground against him, Robinson's foot is resting against his neck. In the background, a cannibal lies dead and, behind him, a dying man tries to stand up, propping himself up on one elbow. The circumstance is in the text: Robinson will lay him at gunpoint, and Vendredi will run to decapitate him. Robinson's massacre of the cannibals causes, produces Vendredi's submission ; Vendredi's submission enables the massacre of the cannibals to be completed : the image does not establish a narrative sequence, but rather a system of equivalences it is indeed the symbolic performance that is represented here.

Picart's engraving for the French translation70 is inspired at first glance by the Dutch composition, which it reproduces in reverse, including the dead and dying. But Vendredi's gesture, captured not in the middle but at the end of the narrative sequence, is no longer the same: he takes Robinson's foot in his hands; kneeling before him, he prepares to kiss his foot. The gesture respects decorum and, as would be theatrical gestures, leaves Vendredi's face unobstructed. The overall composition now adopts the tripartite structure of a scenic engraving, introducing an arm of the sea and a third plane behind the two cannibals. This arm of the sea is mentioned by Defoe: Picart is no less familiar with the text than the Dutch illustrator. The engraving here can be read chronologically from top to bottom: at the top, the cannibals' canoes have landed on the beach it is from here that Vendredi, who was destined to be butchered by them, escapes while they feast on his companion at the bottom, the cannibals' canoes have landed on the beach it is from here that Vendredi, who was destined to be butchered by them, escapes while they feast on his companion : the warrior in loincloth with spear who stands out from the dancing group is one of Vendredi's pursuers, as confirmed by comparison with the woodcut in the English edition of 1752, which depicts the sequence from another angle, from the sea71. Defoe writes that Vendredi is pursued by three warriors, but that only two of them cross behind him the arm of the sea that separates him from Robinson. In Picart's work, these are the two corpses in the background. The one just behind Vendredi is headless: Vendredi has cut off his head and laid it at Robinson's feet. The scenic illustration comes at the end of the narrative and condenses its events ; it organizes the visual simultaneity of the narrative unfolding.

The engraving of 176472 radicalizes Picart's composition: at top left, we find the cannibals dancing, then, below them, the creek, then, lost a little in the folds of the ground, the two corpses, finally Vendredi at Robinson's feet laying the head of his decapitated pursuer. The ritual of the foot has completely disappeared.

Marillier's 1786 drawing for Garnier's Voyages imaginaires returns to the original ritual73 : as in the engraving from the 1720 Dutch translation, Vendredi places Robinson's foot on his head and the cannibal in the background straightens on his knees. But Marillier raises Vendredi's head: the fundamental game is now scopic. Vendredi, lowering himself before Robinson, faces him, and everything is played out in the intense exchange of their gazes, crossed by the master's foot and the slave's arm. For this game, a witness was needed: seated behind Vendredi, his former pursuer acts as spectator. Leaning on the ground with one hand, holding his knee with the other, he's not about to pounce ; he's settling down to watch : it's hard to believe that in a moment whoever's showing him the backside will have decapitated him...

In many ways, the iconographic series produced by Marillier for the Voyages imaginaires marks a decisive mutation : Robinson Crusoe, placed at the head of the collection, henceforth acquires an exemplary and unifying status ; it becomes the imaginary voyage from which all others derive and, from then on, embodies the new anti-utopian utopia which will, along with the Cabinet des fées of which the Voyages imaginaires constitute the counterpart, found children's literature. The first image imagined by Marillier shows Robinson on the shore desperately contemplating the wreckage of his ship74. Alone before the stormy sea and stormy sky, standing on a promontory that unfolds the pre-romantic panorama before him, he is already Friedrich75's Promeneur above the mists. In nineteenth-century editions, the supplicatory gesture disappears in favor of the observer's long view : thus in Percy William Justyne's introductory composition for the 1863 edition76.

The stage doesn't just use the gaze as a vector for formal organization of the performance device. It thematizes it : the illustrator will privilege moments in the narrative where the gaze plays a decisive narrative role. Comparing the illustrative series of Gulliver, for example, we are struck by the emergence of the narrator's gaze. The original 1726 edition features only maps, and also reproduces the book-inventing machine devised by the scholars of Laputa77 : like the Utopians' alphabet in 151878, this machine is inscribed in a world of signs, even before the play of figures that will prepare the advent of the stage. But what stage are we talking about? On the surface, Gulliver bound, with the Lilliputians bustling around him79, is repeated identically in the 1727 French translation by Marillier, in the Voyages imaginaires of 178680, and in the Didot edition of 179781. But on closer inspection, the Lilliputians of 1727 are busy tying Gulliver up without looking at him they even ostentatiously turn their backs on him and occupy the space seamlessly right up to the city that can be seen in the distance. Sixty years later, Marillier chooses the moment when, with the bonds in place, a Lilliputian emboldens himself to come and parley with Gulliver. Mounted on his chest, he addressed him, and Gulliver made an effort with his head to look at him, despite the ties in his hair. All the other Lilliputians, who have stopped fussing, observe the scene, to the left, to the right and behind him: the scenic space is ordered, circumscribed by the circle of spectators. In the engraving after Lefèvre from the 1797 edition82, Gulliver is still asleep, and only the first links are laid. But Lefèvre, like Marillier, places a Lilliputian at the top of Gulliver's chest, ready for the face-off. In the background, a whole army has set off from the city in the background on the right: the Lilliputians' progress orders the space of the representation, and establishes the narrative chronology in space.

In the 1838 edition illustrated by Granville83, this space of narrative inscription fades : Gulliver straightens his head and devours his tiny interlocutor with his eyes. The scenic device itself is engulfed in this devouring gaze.

After the scene : projection and imaginary reserve

Scenic organization in engraving should therefore not be considered as a fixed structure, or as a stable semiotic regime, which would differentiate an illustrative genre from other genres, such as the map or the portrait. The integration or scenic contamination of illustration is a dynamic phenomenon, which presupposes all kinds of intermediate statuses. Formalizing the image as a stage involves inscribing figures in a space and a system of relationships, equating this spatial organization with narrative progression and temporal condensation, and focusing on the exchange of glances and the games of concealment and revelation that this exchange induces. This process is massive, but it is itself relayed by what might be defined as the imaginary overflow of representation, where the scene dissolves.

Marillier's series of 77 drawings for the Voyages imaginaires collected by Garnier is situated precisely at this tipping point, or overflow of the scenic device. The collection created by Marillier features grosso modo only two drawings per volume, which implies a severe selection of sequences to illustrate : the overall effect, which accentuates the evolution of the texts themselves, is so disconcerting that, although the Voyages imaginaires contain the most complete collection of utopian writings published in the 18th century, one may wonder whether this iconographic corpus, taken in its overall physiognomy, still has anything to do with utopia : the beds and alcoves, the greetings, meetings and farewells, the oaths and protests, immediately evoke romantic illustration. Space tightens, privatizes : rooms without openings, groves without perspective, dungeons and caves, evacuate public space, precipitating the gaze into the inner abyss of the imagination.

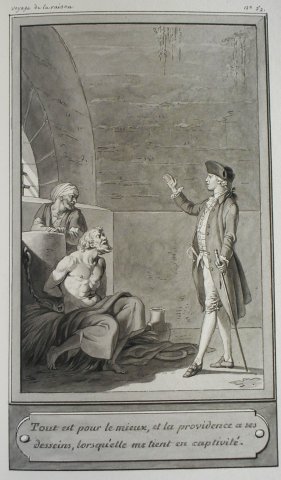

To illustrate Caraccioli's Voyage de la raison en Europe, Marillier chooses the first encounter of reason, who has taken on the guise of the young philosopher Lucidor. The scene is set in the prison where the old man Nabal, victim of the tyrant's injustice, is locked up84. We can barely see the grilled skylight that illuminates the floor from the left: what is most striking is the wide, bare vault that blocks the perspective and smoothes out the space of the representation. The visit to the dungeon is not a new theme, and Marillier can draw on the repertoire of the Roman Charities, from Rubens85 to Lagrenée86. Pero's visit to her father Cimon's dungeon implies the tension between the horrible intimacy of father and daughter, who nurses her to keep her from starving to death, and the surveillance of the guards, either from the skylight, who surprise and observe her, or from the simple presence of the skylight, or from Pero's worried gaze, suggesting the possibility, at any moment, of their appearance. Caraccioli doesn't mention any guards during Lucidor's visit to Nabal's dungeon: they're supposed to be alone. Marillier, however, sacrifices the codes of stage representation, and adds one behind the old man, witnessing their exchange and guaranteeing his visibility to the spectator. But his gratuitous presence, with no dramatic consequences, neutralizes him in a way here, it's the wall of the dungeon that becomes the main actor in the scene, bearing the phrases of the venerable old man " I had a brilliant place that could have dazzled me, I'm only concerned here with my soul, which it's impossible to enchain. I raise it above this body that you see captive, & I walk it in spaces a thousand times more vast than Turkey. " (Voyages imaginaires, t. 27, p. 143.)

The wall of captivity projects the immensity of the world traversed by the sage's soul the narrowing of this collapsed scene upon itself constitutes a new imaginary reserve, the spring of a new possible expansion. Contrary to what the legend suggests, the moment chosen by Marillier is not that of the old man's stoic words, but of Lucidor's reply, whose raised arm accompanies his speech: " There is neither prison nor exile for an elevated soul, Lucidor replied, the walls fall down at the sight of a man who looks upon the earth as an atome, & who holds only to his duty. " The wall of the dungeon is destined to fall the spectacle of virtue makes the wall fall the eye of the soul revolts against this chamber of persecuted innocence and reason calls for a new freedom.

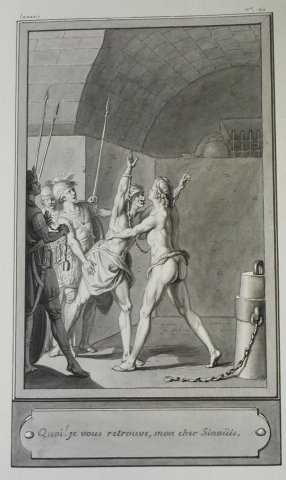

Similarly, Marillier's final illustration for Lamékis by Chevalier de Mouhy87 depicts the reunion of Sinoüis, the man-hibou, with Lamékis in the underground apartment where his wife Clémelis has been locked up by Zélimon. Lamékis, changed into a snake, regained his human form by slipping into Clémelis' bed, but Clémelis was abducted by Zélimon during her sleep. Lamékis found himself alone, naked and locked up. In Marillier's drawing, the guards, or culambis, escorting Sinoüis stand behind him one of them, in the left foreground, holds in his hands the chains with which he will soon load Lamékis in Sinoüis's manner. A bollard to which a chain is sealed (somewhat incongruous in what is supposed to be an underground apartment !) indicates the captivity to which they are destined. The vaulted dungeon, with its smooth wall against which the embrace of the two friends stands out, could be Nabal's in the Voyage de la raison and serves the same purpose as the grotto in Marillier's first drawing for Lamékis88, where young Lamékis finds himself taken in the same cave appears the same year, following L'An mille quatre cent quarante, to illustrate Mercier's L'Homme de fer89. For Lamékis, Marillier uses the culambis stopped behind Sinoüis as witnesses to the reunion scene, in the same way that, in the Voyage de la raison, the guard behind the old man witnessed Lucidor's coming. Even if there is nothing here to evoke the paradoxical freedom of the Stoic in irons, the heroic captivity of the faithful friend and constant husband is the pretext for the long mutual recounting of the adventures that led them to each other : the dungeon does indeed operate as an imaginary reserve where an interminable narrative comes to be projected...

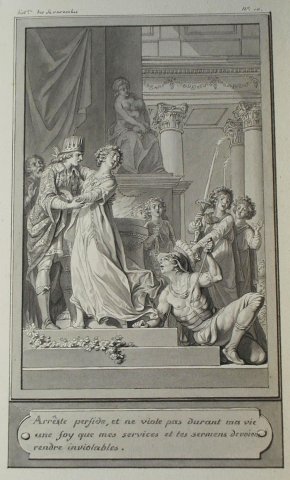

The second drawing for the Histoire des Sévarambes seems to contradict this trend90. It's not in a dungeon, nor in a secret apartment, but before the very official altar of the Temple of the Sun that young Calénis is depicted in the arms of the viceroy Sévaristas whom she is about to marry, betraying her faith given to Foristan. The unfortunate young man emerges on the right at the bottom of the altar steps and attempts suicide. The story has a happy ending: Foristan does not die, Calénis, overcome with remorse, returns to him, and Sévaristas generously renounces her. The scene is reminiscent of the much more tragic story of Corésus and Callirhoé, either in Fragonard's version for his tableau d'agrément91, or rather in the one engraved by David Coster after Robert Duval to illustrate Destouches' opera in the Recueil des opéras published in The Hague in 171892. The model for this is undoubtedly the great history painting, which stages a public and political space, the very one targeted by the classic utopian discourse.

But precisely the painting of Calénis caught between her two lovers is only a painting : Marillier draws from Vairasse's description of the painting hung in the Temple of the Sun to commemorate the magnanimity of Sevaristas. Each viceroy is commemorated in the Temple by an exemplary scene, the series of which constitutes, in Vairasse's text, a utopian discourse of exemplarity. From a semiotic point of view, it's a scene in the second degree: the scene in the Temple is a representation of a scene, the public space that unfolds is itself inscribed within the space it represents, and the action is given to the Sevarites to ponder before being delivered to the reader. The same phenomenon can be observed in the similar scene from the Mémoires de Gaudence de Lucques, illustrated in the English edition of 178693, where Berilla, who has given tokens of love to the Pophar's two sons, is condemned by the latter to celibacy. The younger son steps in and generously gives up his place to his brother. Gaudence, the narrator, who has become the official painter of the Mezzoranians, makes a painting of the scene, which he offers to Sophrosine, the daughter of the Pophar with whom he is in love, so that what we see in the image (as what we read in the text) is not strictly speaking the event itself, but its representation by Gaudence, whose virtuous exemplarity is mediated by the story of Sophrosine in which that of Berilla is embedded.

In both cases, what the reader reads and sees is not directly the event, but its commemoration : we are therefore well within a logic of imaginary projection. The mediation of the painting takes many forms. For example, the throne room depicted on the frontispiece of Volume II of the 1786 edition of L'An deux mille quatre cent quarante by Sébastien Mercier94, whose composition is very close to the painting in the Histoire des Sévarambes illustrated by Marillier, shows us the King's daily audience : he is being read the day's news by a councillor on the left, and is about to hear the grievances of a young woman who has stepped into the foreground on the right. Here, public space unfolds in all its majesty, in the presence of the assembled people, and in the solemnity of a vast hall with Corinthian columns of the greatest style. But an inscription draws our attention: " Eternity ", on the first step of the throne. As Mercier's text makes clear, the king is in fact seated on the tomb of his predecessor, a tomb destined to become his own when his successor takes over. In this image, everything is in place to ward off temporality: it does not represent the event of a particular audience, but the regularity of the daily audience; it deploys the King's pomp only as a gangue enclosing the sepulchral core of the tomb of all kings; the scene nurtures at its heart the imaginary reserve of this tomb and the majestic anxiety of the inscription it bears. The theatricality of the event is replaced by the permanence of the monument.

.

The iconographic series of L'Île inconnue, in the Voyages imaginaires, even more explicitly mobilizes the representation of the monument to supplant the exemplary scene and refer to a second representation: the last engraving is entitled " Monumens élevés à la mémoire des Bienfaiteurs de la Patrie95 ". We see an arched gallery towards which the walkers converge: the exemplary scene is the end point of the walk, the content that is projected onto the gallery wall ; but on the image this content is invisible.

The introductory vignette from the second part of the Mémoires de Gaudence de Lucques, engraved in 1752 by Fessard after Le Lorain96, depicts the sacrifice of Mezzoranian travelers to the memory of their ancestors as they enter the territory of their homeland. The scene is bathed in the rays of the sun, the Mezzoranian god. On the right, the travelers prostrate before the altar where the Pophar officiates; on the left, Gaudence watches with some repugnance a ceremony that seems to him pagan and idolatrous ; behind him, one of the three camels turns its head curiously, as in the depictions of Eliezer and Rebekah97. To implement the scenic device in a reduced space, Le Lorain departs from Berington's text, doing away with the Egyptian pyramid and the statue on the ceremonial altar. This simplification universalizes the scene, organized in concentric circles according to the rules of classical composition first the travelers lying on their stomachs around the altar, then Gaudence standing hesitating between staying and leaving, finally the camels.

The same sequence is illustrated by Walker after Burney in the English edition of 1786, 34 years later, in a full-page composition98. Burney reintroduces the pyramid, not to place the altar at its summit, but as a backdrop in front of which the ceremony takes place. Gaudence and the camel are moved to the lower-left corner, in shadow, answered by the shadow of the forest in the upper-right corner. In contrast, the brightly lit pyramid introduces a broad diagonal of light on which the ritual of the Pophar and his acolytes is based. Its surface acts as an imaginary projection surface, surrounded by the darkness in which Gaudence finds himself as spectator, which is also the darkness of the dream and the forest. In a completely different context, and even more explicitly, the pyramidal column on the frontispiece of Volume I of L'An mille quatre cent quarante (1786)99, where the narrator discovers posters of future Paris, functions doubly as a surface of projection, not only for what is discovered and inscribed there, but because the texts displayed there speak of projection in time.

Imaginary projection and reservation signal the death of the classical stage and the theatrical paradigm it had tried to generalize. At the same time, utopia ceases to be thought of as a stage in the narrative journey of the voyage, to be deployed in the withdrawal of the imaginary pocket it provides. Scenic representation would long survive in nineteenth-century iconography, but as an exercise in style that was undermined by other functions of the figure, other articulations of space. Contradictorily, the post-scenic space of the performance opens up beyond the theater (as the power of nature, as the mirage of technique) and closes in behind its characters (in secret melancholy and sorrow, in intimate memory and injury). This double movement marks the advent to the image of the invisible interiority of dream and vision, towards which Garnier's Voyages imaginaires collection was already tending. The introspection thus initiated undoes the frames and structure of the theatrical stage, unleashing the enjoyment of boundless spaces. The bubbling of the storm, the unfolding of panoramas, the reverie over tombs thematize this double movement. The 1806 edition of Paul et Virginie, a novel whose textual construction is still that of the classical utopia, offers exemplary images : the Passage du torrent, engraved by Roger after Girodet100, takes up the iconography of Aeneas and Anchises, which Raphael had already transposed in L'Incendie du Borgo101. But the space surrounding Paul bearing Virginie is completely turned upside down the fire of Troy or Rome, with its actors and witnesses, designated the event and composed the set of companion figures on which the exemplary figure was differentially inscribed the torrent, on the contrary, substitutes the difference and inscription of figures with the dissemination of its sheaves and the whiteness of its whirlpool. Its bubbling is reflected in Virginie's terrified gaze, which literally absorbs, penetrates and undoes itself. Paul, observing her terror, is not the spectator of a scene, but the overhang of a collapse.

Similarly, the shipwreck of Virginie, engraved by Roger after Prud'hon102, contrasts with the dramatic scene imagined by Vernet in 1789, with its backdrop, spectators to one side, and the dramatic action of lamenting the corpse in the foreground103. There's nothing like that in Prud'hon's work, where Virginie stands alone on the gutted hull of her sinking boat, just as the foam of a reversing wave is about to engulf her. On closer inspection, a drowning companion can be seen in the lower right-hand corner, and behind him, shadows on the shore are busy trying to rescue the shipwrecked. But the powerful protagonist who crushes everything is the wave in which Virginie is caught: the image feeds off this scenic collapse, which constitutes an imaginary reserve. This shipwreck is depicted as a suicide and as an exhibition, with the same pathetic coloration as the Sapho à Leucate painted by Gros in 1801104.

Finally, the last print, engraved by Pillement fils and Bovinet after Isabey105, participates in the same imaginary economy : to the left of the lovers' tombs arranged in the bamboo grove, a melancholy, empty alley leads to a blinding shaft of light. The enclosure of the tomb is thus placed in equivalence with the vague, infinite opening of the path towards the light: Envelopment in the abyss and vague openness, reserve and projection constitute the two poles between which the new semiotic economy is unfolding, giving rise to the machines and secrets of Jules Verne's novels.

Notes

All the engravings mentioned in this article are described and reproduced on Utpictura18. They can be found, with their precise references, by going to the search page and typing the record number in the field provided (the search engine accepts both old numbers that start with a letter, and new ones that are numbers only). Here, notice B1911. Wherever the layout allowed, images were integrated into the text.

B1912.

A3233 et seq.

A2333 et seq.

B1645, B2306.

B2128.

A5579, A5580, A5581, A5582.

B2089.

B1607.

On the first map depicting it, in 1600, Nova Guinea is not clearly delineated as an island : only its northern coast is detailed.

B1658.

B2031.

B2096.

A3358.

B2129.

A7477.

B1682

B2061.

A5585.

A5586, A5587, A5588, A5589.

A8014.

B1584.

B1600.

B1586.

B1631.

B1624.

B1644.

B2163.

B1660, B2099, B2106, B2119.

B2067.

B1641 ?

B1576.

B1700.

B1578.

B1653.

B1715.

B1720.

B1739.

B1714.

B1657, B2095, B2104.

B2110.

B2111.

B2115.

B2117.

B2124.

B2274.

B2275.

B2276.

B2278.

B2173.

B2176.

B1659 and B1660.

B2064.

B2067 to B2081

B2058, B2059.

B2060.

B2056.

B2035.

B2034, compare with B2035 and B2251.

B2041.

B1923.

B2042.

B2043.

B1588, B1603, B1625, B1172...

B2171.

B1649.

B1633.

B1626.

B2261.

B1590.

B1618.

B1627.

B1173.

B1172.

A3411.

B1828. See also A9295, B1837, B1840, B1856, B1858, B1865, B1869.

A5583.

B1910.

A5586.

A8015.

B1701.

A8015.

B2252.

B1724.

A1645, A1823.

A1159.

B1714

B1711.

B2281.

B1643.

A0418.

A9546.

B2093.

B2280.

B1691.

B2091.

A7415.

B2092.

B2282.

B2264.

A3987.

B2267.

A5493.

A2269.

B2268.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Illustrations de l’utopie au XVIIIe siècle », Dictionnaire critique de l’utopie au temps des Lumières, dir. Bronislaw Backo, Michel Porret, François Rosset, Georg Editeur, Chêne-Bourg, Suisse, 2016, p. 565-596.

Fiction, illustration, peinture

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Fiction, illustration, peinture

La scène de roman

La scène de roman : introduction

Renaud dans le jardin d’Armide

Rastignac chez Mme de Restaud

Gilberte derrière les aubépines

La poignée de porte de tante Berthe

La double aporie du topos

Illustrer la fiction

Molière, une parole débordée

Marillier, l’appel du mièvre

On n'y voit rien

Illustrations de l'utopie au XVIIIe siècle

Le temps des images

Du conte au roman graphique

Déconstruire l’illustration

Régimes de la représentation dans la gravure d’illustration classique

Penser la fiction depuis la peinture

Une sémiologie du décalage : Loth à la scène

Introduction à la scène comme dispositif : Paolo et Francesca

La main tendue, le regard démasqué

De Silène molesté à la chair blanche des nymphes

Chambres de la représentation

L'intimité de Gertrude

Brutalités invisibles

Parodie et pastiche de Poe et de Conan Doyle dans Le Mystère de la chambre jaune de Gaston Leroux

Le dispositif de la chambre double dans Les Démons de Dostoïevski

Scène pour voir et chambre des brutalités

La Princesse de Clèves

L’invention de la scène dans le roman français

La canne des Indes

L'aveu

La princesse, la religieuse et l'idiot

Richardson

Entre scandale et leurre

Introduction aux Lettres angloises, ou histoire de miss Clarisse Harlove, par Samuel Richardson