The purpose of this article is to propose a genealogical model of the representational regimes that organize the image in classical illustration printmaking. A regime of representation is defined by the concordance of a device in the image and a social, cultural or political context in which this image is produced and then used. This involves correlating recurring formal dispositions (organization of space, relationship between the groups occupying it, functions of these groups and ways of signifying) with reading practices themselves conditioned by the reader's representation of the society in which he or she is caught.

For such modeling, it's interesting to work on a corpus of images spread over time but always illustrating the same text: the same textual content gives rise to different images; modeling the regime must free itself as much as possible from the variety of content. It's the variation in representations that interests us here. In this respect, the illustrated manuscripts and editions of Virgil constitute a privileged corpus, enabling us not only to cover the entire period, but also to refer to the earliest Roman illustrations that have come down to us.

Performative regime: the image as a supplement to recitatio

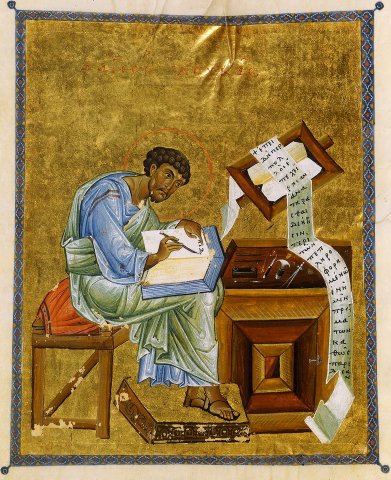

The Vergilius Vaticanus is one such manuscript1, produced at a time when the codex (the bound book) was definitively taking the place of the volumen (the scroll).

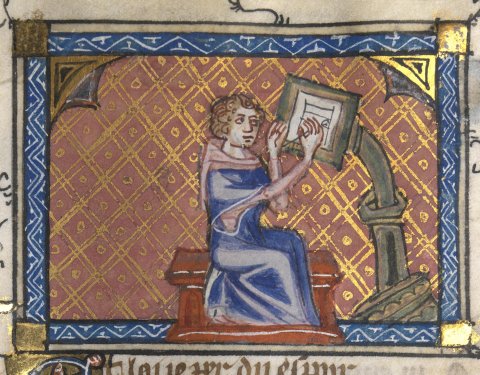

The rubricator's work comes last: the scribe has previously written the text, from the empty space left by the image. In a sense, the space left empty by the copyist before the illuminator intervenes sets the basic function of the image: the image delimits a space, which the text fills. The inaugural gesture of image creation is the delimitation of this space2.

Reading the codex will repeat the process of its making; this process itself transposes, or supplants the process of creating the text itself, which is ideally accomplished in the recitatio, when the author summons his friends for a reading that is to launch his publication. The recitatio is not the reading of a completed text to which the guests passively listen: it is itself a performance that co-creates the text by soliciting the participants, who can share in the reading, criticize it, and must above all by their presence bring their endorsement. The recitatio may or may not have taken place before the manuscripts were copied; when it did, it was always described as a disappointing experience. Still: reading will always mimic this performance, make up for its founding defect3, just as writing the text in the manuscript makes up for the defect in the image that precedes it.

The image will thus read as the inaugural installation of this default performance. Let's take an example.

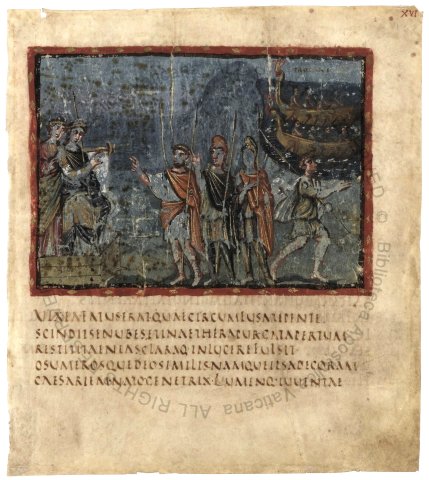

On f. 16r° left, Dido holds audience on a wooden throne before the temple of Juno (c. 506). Aeneas and Achate stand before her. There is no trace in the image of the cloud of invisibility provided by Venus, which dissipates before Dido. The verses that follow the image describe their miraculous appearance before her (v. 586-590).

The image is read from left to right and hierarchically. The subject phrase on the left represents Didon enthroned, her sister Anna behind her. The queen commands the image, is its subject; her precedence as the subject who orders the performance is marked by the confidante who accompanies her. The object of Dido's audience is Aeneas facing her, followed by two Trojans in Phrygian caps. The regime syntagm is in turn composed of a figure who commands, Aeneas with his arm raised, and two figures under his orders.

The right-hand side of the image represents a third phrase: Achate turns his back to the other figures as he leaves the scene. Achate's head is lower than Aeneas', which in turn is lower than Dido's. Achate is the object of Aeneas' command, who dispatches him to the Trojan ships (v. 644) to fetch his son Ascanius. Achate depends on Aeneas, who depends on Dido. The phrase ordered by Achate is itself made up of three elements: Achate is the subject, while the two ships depicted above him represent the object, the destination of his action. Of course, these ships are not visible, in the modern sense of the word, either from Dido, or from Aeneas, or even from Achate as he leaves Aeneas.

The image lays out the hierarchies on which the Virgilian narrative, on reading the text that follows it, will come to be grafted. The content of the image, then, is not the narrative, but the hierarchy that conditions it. Performance consists in actualizing this hierarchy. Performance is not a succession of narratives. It establishes a permanent relationship, which generally boils down to one of sovereignty. Sovereignty is exercised over a territory: the background and frame of the image delimit this territory. Here we touch on the fundamental basis of the visibility regimes of the so-called illustrative image, which later devices will encapsulate, without ever completely making it disappear.

.Narrative regime: territories, altarpiece, parade

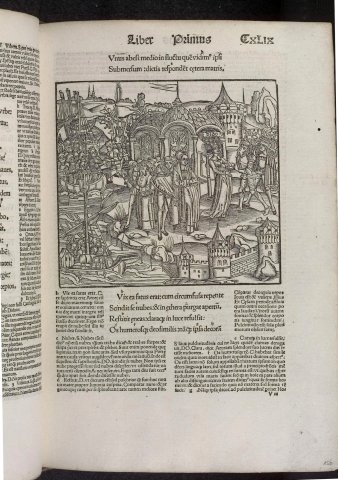

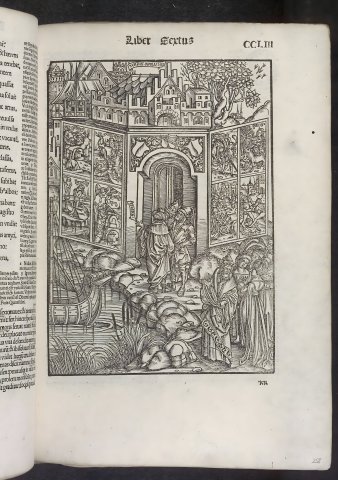

A thousand years later in Strasbourg, the printer Jean Grüniger published in 1502 a Latin edition of the complete works of Virgil illustrated with woodcuts by Sébastien Brant, the author of La Nef des fous4. Like the miniatures in the Vergilius Vaticanus, the 1502 engravings precede the text. To analyze the transformation of the image regime, let's take, on f. 149r°, the engraving that depicts Dido welcoming Aeneas to Carthage, and is inserted, like the image on f. 16r° of the Vergilius Vaticanus, just before verse 586.

The overall space in which these various episodes are arranged - the arrival of the boats at bottom left, Dido's welcome at top right, Ascanius' invitation at top left - is now part of a topography, articulating the city of Carthage to its Tyrrhenian shores and rural horizon. The circulation of the gaze across the image map serves to narrativize the regime of visibility. Below the temple, which dominates the city, Brant has depicted the assembly of burghers who govern the city and form the interface of all circulations5. This group of characters does not correspond to any textual element. It is in the economy of the image that it makes sense, as a supplement to the subject phrase, whose function the queen no longer occupies. The queen on the right manages Aeneas' welcome, just as the soldier on the left manages Ascanius' invitation. Both are mediators of the sovereignty of the city-world, signified by the temple and embodied by the burghers assembled behind Dido, at the center of the engraving.

The image now assumes that one circulates in front of it, as the faithful circulated in front of church altarpieces6. The structure of the triptych serves as a model for deploying, even on supports that no longer have anything to do with it, a three-in-one device anticipating the lateral and successive reading that will be made of the image, and at the same time, at its conclusion, the return to embrace one last time with the gaze what we have paraded before: it is notthe look but a parade of spectators that began by structuring the semiotic regime of the modern image.

In Sébastien Brant's engraving for folio 149 of the 1502 Virgil, we enter the image through Aeneas' ship on the left, and aim from the outset at the opposite of the image, Dido's hospitality in the upper right. The exit is Ascanius, the story's climax. But Ascagne himself gets off the boat, and is summoned to join his father in the city. The arrival point thus indicates a return. The characters' journey through the image, and the trampling of Carthaginian onlookers at its center, create an abyss for the spectator-reader, who himself transposes the procession in front of the altarpiece, with its ultimate quarter-turn. The engraving thus supplants the altarpiece, just as illumination supplanted the recitatio.

The reasons why the ritual of devotion before the altarpiece came to serve as a model go back to the origins of medieval silent reading, which is no longer defined as an artifact of the recitatio, but as an artifact of prayer. Reading is a transfer of devotion, which means that image reading takes place through the transfer of the devotional relationship to images.

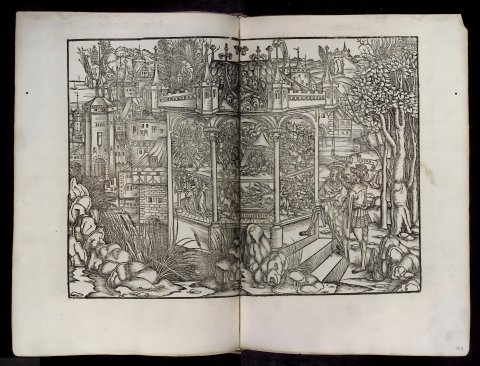

The double-page composition (the only one in the book) depicting Aeneas and Achateus admiring the historiated façade of Juno's temple bears spectacular witness to this7. Virgil himself had conceived the text as a Roman mise en abyme of Greek epic performance, for which the Vigilian text provides the artifact. As the text produces a simulacrum of epic, the book provides the artifact of a recitatio, and the 1502 engraving represents an image within the image, the transposition into the image of the devotional performance that the image supplements. The façade of the temple, with its three arches, its two registers of representation, lower and upper, and its eight scenes from the Trojan War8, in fact bears no resemblance to an ancient temple, or even to the exterior of a contemporary church, but precisely to a Gothic altarpiece in front of which one can come and parade to admire the images. No door is provided to enter an edifice: the temple is reduced to the structure of a triptych, which is not even that of a flat façade; its polygonal shape suggests, in an inverted form, that of the side shutters, which are opened or folded back9.

Discursive regime: depth of image and bipartition of space

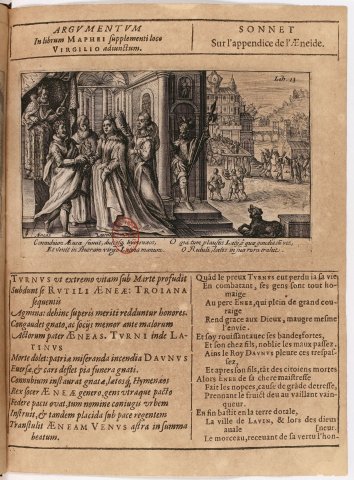

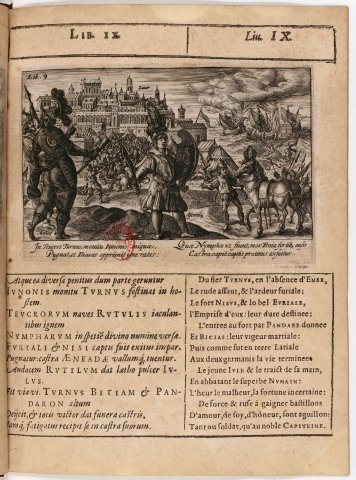

Scrolling and summary: these two contradictory tendencies of the narrative regime of representation that is being established then profoundly transform the very status of the image. The Compendium operum Virgilianorum published in Utrecht in 1612 bears witness to this. To do this, we need to start with the last engraving in the collection, which illustrates the apocryphal thirteenth book of the Eneid, composed in 1428 by Maffeo Vegio.

The engraving depicts on the right Aeneas receiving the tribute of the Rutuli on the death of Turnus, on the left the ceremony of Aeneas' marriage to the daughter of Latinus, in the center a banquet on the esplanade in front of the royal castle, celebrating the completion of the new city of Lavinium, whose houses can be seen in the background10. The image is thus organized into three territories, each containing a narrative unit, with the city at the center forming the neuralgic interchange. But of these three, the wedding episode is hypertrophied, tending to become the exclusive scene, of which the other two episodes constitute the landscape, the decorative background.

In this very scene that emerges in the image, the old structure of the altarpiece persists, with its three panels, the left, where Latinus in the pulpit presides over the ceremony, the central panel, where Aeneas and Lavinia exchange their consents in the presence of a priest and a maid, and finally the right panel, where a halberdier seems to leave his post to, from behind the column, fully enjoy the spectacle.

The four protagonists, though distributed in two shots - Aeneas and Lavinia in front, the priest and the follower behind - appear in line11: they do not occupy the space of the nave. The Latinus pulpit is, as it were, propelled onto the forecourt, and the old logic of surface and lateral reading prevails.

But the paving of the floor, the double colonnade at the back of the temple, the steps of the staircase, the balustrade surrounding the banqueting table, the table itself arranged in cavalier perspective, the bridge and the landscape in the background on the right, if they don't yet contribute to a single vanishing point, organize a depth of the image, on the left the space of the temple with its apse, on the right the space of the city with its castle. Between these two spaces, linked by a staircase, the halberdier and the dog do nothing but look: they are there merely to signify that, faced with the image, the fixed position of a gaze must be assumed. We are in the process of moving from a regime of commentary (the narrative regime) to a regime of point of view, from a common regime of text to a regime proper to image.

Latinus on the left, scepter raised, gives away his daughter and pronounces the marriage; the priest, between the spouses, blesses the union. The idea here is no longer to draw a chronological path through the image: a scene of discourse is surrounded by a horizon of events. From now on, the image tends to organize a division: to the scene itself belongs the speech, its representation, its staging, while the events are relegated to the decor, the distance, and soon the vagueness of the representation. Thus, through speech, the literate bourgeois can appropriate the heroic event to which his class should not give him access; through fiction, he makes his own a virtualized chivalric glory.

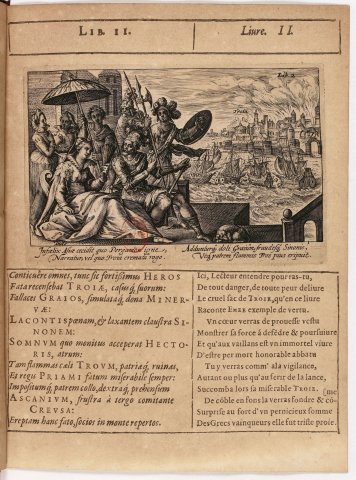

Book II of the Eneid lends itself wonderfully to this supplanting of performance by discourse: Virgil does not, in fact, recount the Trojan War but its recounting by Aeneas to Dido12. Whereas the 1502 engravings directly depicted the fall of the city, it is indeed the space of enunciation that the Compendium of 1612 (#018523) stages.

In the left foreground, Aeneas is seated next to Dido on a dais above the sea. Aeneas is crowned in the manner of a king, as if he were already the queen's husband, which won't happen until Book IV; he has donned his fighter's breastplate, which is hardly compatible with the courtly apparatus and banquet festivities. The space in which Aeneas finds himself is not, strictly speaking, the space of the banquet, understood as an event in Book II: there are no tables, seats, dishes or balustrades between the terrace and the sea. It's a space of the Sign, where the characters put on the signs that designate them hierarchically and symbolically. Aeneas wears a cuirass and armor, just as Euryale, in the illustration for Book IX, wears the plumed helmet he had not yet taken from Mézence. He who speaks puts on the garb of glory; speech is worth distinction.

This virtual terrace, where Dido and Aeneas are seated, surrounded by their court as audience, contrasts with the background, treated in lighter tones, which Aeneas is pointing at. The image is divided between the restricted space of the scene in the foreground, dedicated to the eloquence of the narrative, and the vague space of the setting in the background, unfolding the events recounted, the departure of the Greek ships for Troy, the origin of the war, and then, in the far right, the introduction of the horse into the city and its burning, which marks its end. Relegated to an increasingly vague distance, the management of discourse signs will gradually disappear.

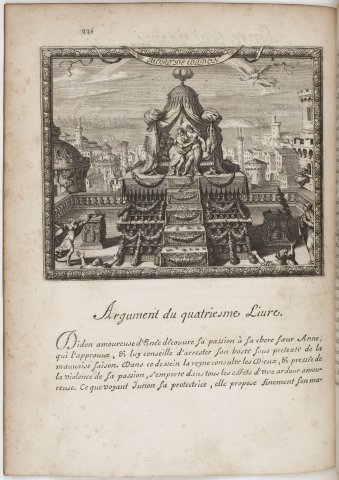

The Énéide en vers français dedicated to Mazarin in 1648 provides a particularly striking example of this evolution. In fact, only the first six books appeared in 1648, as publication of the second volume was interrupted by the Fronde13: it was not published until ten years later, with engravings of a rather different workmanship. In the 1648 volume, the engraving illustrating Book IV, said to be by Abraham Bosse14, depicts Dido's suicide.

In the center of a vast terrace surrounded by a balustrade and overlooking the harbor, a pyre is erected, adorned with festoons and roses. Atop the pyre, on a platform, is a bed, itself topped by a baldachin. Aeneas' fleet fades into the horizon on the left, while the goddess Iris appears in the upper right, at the base of a rainbow, brandishing the scissors with which, by cutting a lock of her hair, she must free Dido's soul from her body15.

The vague space does indeed contain the events in which Dido's death scene comes to be inscribed: it is because Aeneas has left that she commits suicide; it is because she commits suicide that Juno, out of commiseration, sends her Iris to prepare her welcome to the Underworld, where she was not yet expected. From left to right, the image presents the three successive territories of the Virgilian narrative: Aeneas' departure, Dido's suicide and Iris' arrival. But the hypertrophy of the central episode and the relegation of the other two episodes to a discreet grisaille setting here clearly mark the need to move from a lateral reading of an altarpiece to a plunge into the depths of the image.

.In the very foreground, Bosse introduces frightened onlookers who rush to the dying queen. The staircase in the center of the engraving that leads to the top of the pyre accompanies the viewer's gaze from a supposed fixed point in front of the image to the funeral bed, in the exact center of the engraving, where Anna holds her embracing sister. In the background, between the canopy curtains, the eye reaches the sea, behind the tassels of the cord that, inside, must tie them.

Above the dais placed atop the pyre where the funeral bed was erected, the canopy imagined by Abraham Bosse is that of a catafalque, itself conceived in the manner of the biblical tabernacle, whose device since the Council of Trent has commanded the new theology of images.

Perspectival regime: screen and tabernacle

The shift from the altarpiece to the tabernacle as a referential model for the relationship to the image ratifies the assignment of the reader-spectator to a unique place in front of the image, which the now unique vanishing point, symmetrically facing it, comes to signify16. The substitution of the tabernacle17 for the altarpiece primarily requires an effect of depth, and introduces into this depth a principle of interposition, transposing the crossing of the tabernacle veil to pass from the Holy to the Holy of Holies. In the scenic device implemented by this new regime, this crossing will take place from a vague space, from which the spectators watch, to a restricted space, where the protagonists are watched.

.In France, this mutation took place at the end of the Fronde, when the feudal regime, with its territories and franchises (free towns, free ports and other local exchanges), was evolving into an absolute monarchy that centralized power and assigned everyone their place in a social hierarchy that it codified and stabilized18. Unifying points of view, stopping the parade of spectators, bringing the archipelago of territories back to the simple game of Court and City, of what makes sense and what makes landscape: the mutations of the semiotic regime of the image prefigure or transpose the strategy of royal power, which itself invests the new devices politically.

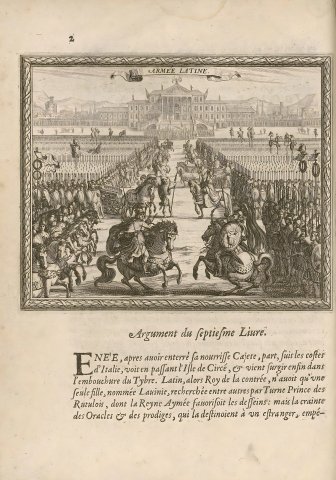

The second volume of the Énéide traduite en vers français, published in 1658, opens, to illustrate Book VII, with a representation of the Latin army in cavalier perspective. Virgil's Latinus watches helplessly as the armies hostile to Aeneas gather, and soon locks himself away in his palace. In the image, he can be seen at the bottom of the stairs, seated under a parasol. He may not be reviewing his troops, but his gaze dominates them: reduced to a single point, he is placed just below the vanishing point of the cavalier perspective, i.e. at the nerve center of the image. From this point, he controls the whole.

The reader of 1658 could not fail to make the connection with the recent events of the Fronde19: in Turnus's revolt, he found the echo of the revolt of the Grands; in Latinus's fragility that of the king's authority. The introduction of a rigorous linear perspective organizes the reversal of the balance of power. The Great Ones look good in the eyes of the little king, but are no more than figures in the court ballet he orchestrates from his palace.

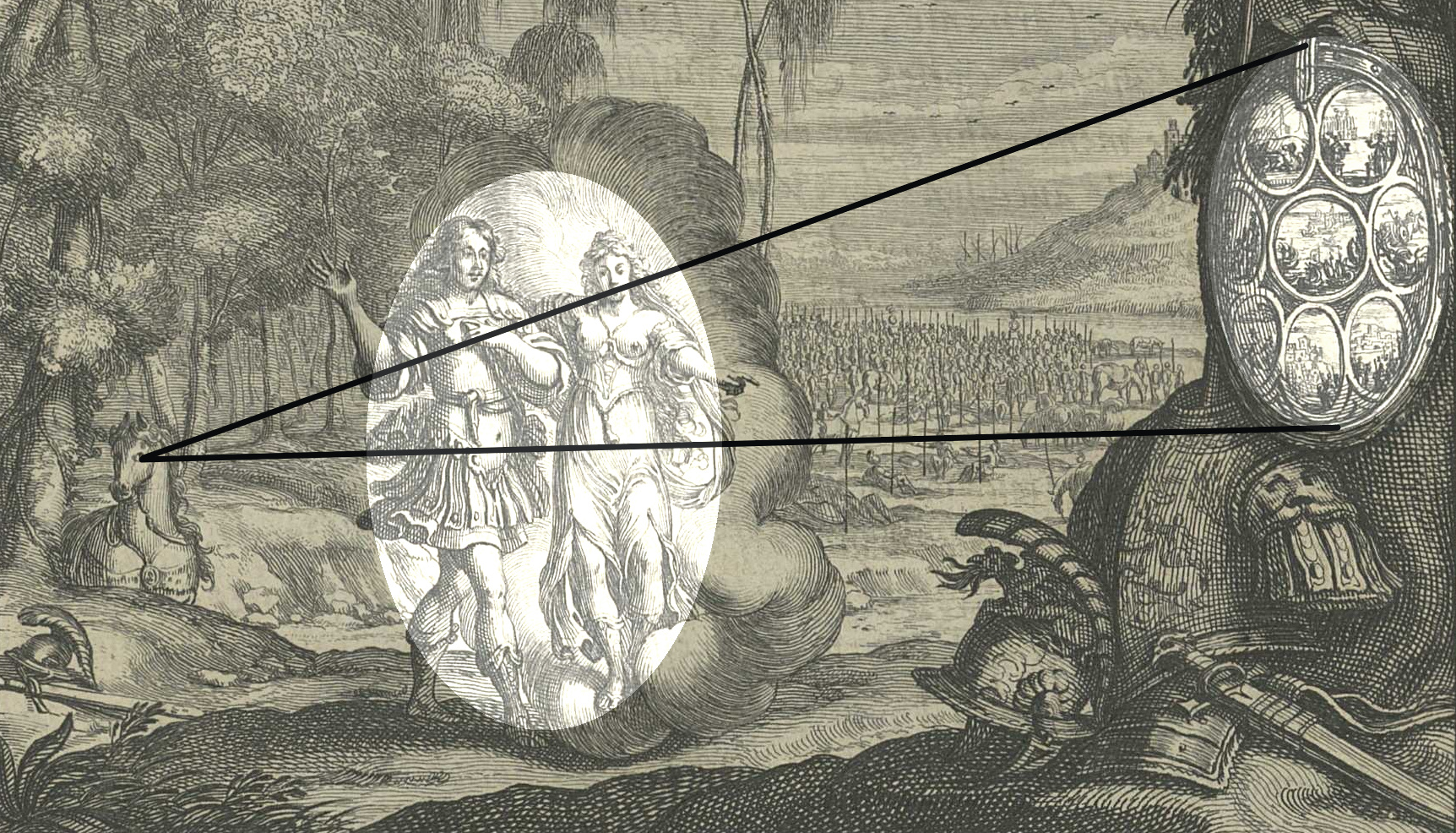

In the engraving in Book VIII, where Venus presents Aeneas with the weapons Vulcan has forged for him, Abraham Bosse clearly separates a foreground, on the right, where the weapons are arranged around a tree in the manner of a trophy, from a second foreground in the center, where Aeneas advances alongside Venus who leads him, surrounded by a cloud indicating her divinity, and a third plan on the left, from which Aeneas' horse observes the scene20. The Latin army assembling in the previous engraving here occupies the background of the image.

The composition retains the memory of the old triptych narrative organization: Aeneas and Venus on the left (actually in the center), the Latin army in the center (actually shifted to the right), Aeneas' shield on the right. The background, now essentially decorative, is at most the subject of Venus' speech (v. 613-614), which is superimposed by the group she forms with Aeneas. The composition is now divided into a space that is looked at (the trophy) and a space that looks (Venus shows Aeneas her weapons), itself breaking down, according to the same principle, into a group looked at (the goddess and her son) and Aeneas' horse looking at them.

Or from where he's been left, the looking horse can see nothing but from behind, as from where they are the goddess and hero can hardly observe the details of the shield. Despite the movement of the horse's head and the grand, demonstrative gestures of Aeneas and Venus, the focal object of attention, which gives meaning to the scene and the composition as a whole, remains absolutely invisible to them.

.In contrast, the reader enjoys being able to see what no mortal is supposed to witness. In other words, the scene reveals itself to the viewer as the Holy of Holies: deliberately obscured to bring out the scene behind him, the foreground now functions as an interposed threshold between the reader's eye and the scene itself21 - Aeneas and Venus coming forward - while reciprocally the protagonists interpose their backs between the horse's gaze and the trophy. On the threshold of the image is stored the shield that contains the ekphrasis, i.e. the quintessence of both eloquence and image. Placing the image on the threshold is the principle of the tabernacle, whose veil alone escapes the ban on representation.

Thanks to these interpositions, the scene is defined as a restricted space delimited by the trophy in the foreground, the horse and the Latin army in the background. The restricted space is the section of the cone where the vision is produced, between the gaze that commands it (the horse) and the events it will trigger (the story of Rome on the shield). A scene occurs when the reader no longer reads the events directly, but a representation (the text, the image) of their representation (the shield). The scene substitutes eloquence for action, and transfers the action to the vague space surrounding it (the shield at the edge of the engraving). Nothing happens on stage other than the transition to representation (Aeneas looks at the shield Venus shows him).

This staging of speech constitutes the last vestige of the old performance regime, which subsists through it in the new economy of the gaze while all action is relegated to the vagueness of the periphery.

No doubt that A. Bosse22 draws inspiration from the theatrical scene when he illustrates Book VIII: in the priming of Aeneas' gait as he advances towards the trophy of arms offered to him by Venus, we recognize the exaggerated, codified gestures of theatrical expression, the enthusiasm of the right arm raised backwards, the gratitude and love expressed by the left hand over the heart23. Similarly, Venus's cloud is comparable to Medea's clouds in Baroque opera sets24.

The appearance of theatrical gestures and props on the engraving stage is an effect of the regime change; it is not the reason for it. The theater that is exported here as a model is not theater as a genre, or as an acting practice; it is the organization of the performance based on a certain disposition and conception of the audience, whose ideal position becomes unique and fixed, in the center of the parterre, from which to deploy the performance on stage. The theatrical model makes it possible to assign places to everyone: it begins by sharing the stage and parterre25, then within the stage it levels the planes according to the backstage26. The layering of the shots hierarchizes them, just as the seats in the auditorium, the positions of the audience and the order of society itself are supposed to be hierarchized. Linear perspective tends towards this order, whose representation is only possible through it.

The French Virgil, moreover, is based on a fundamental division: to the bipartition of the image proper to stage devices corresponds that of the text in the book, with its alternating Latin and French pages. Here, Latin becomes a vague space, whose referential value takes the place of an event; French constitutes the scene proper, the exercise in eloquence, the representation of representation.

Critical regime: the image after the event

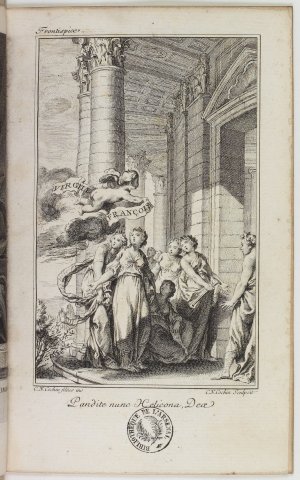

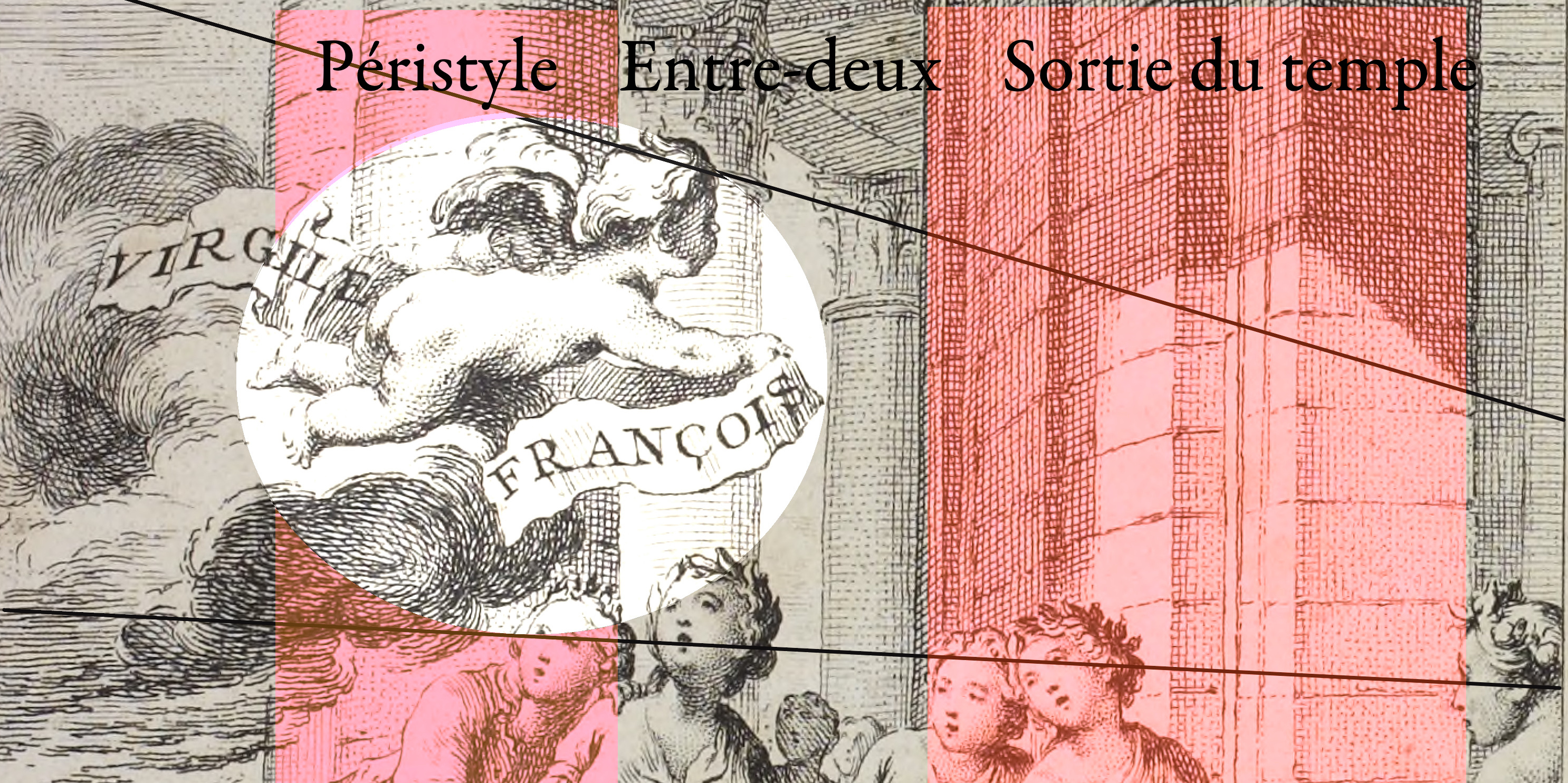

When, almost a century later, Abbé Des Fontaines published a new translation of Virgil in 1743, it was no longer as a translator that he presented himself primarily, but as a journalist and critic. This is the message of the frontispiece engraving by the very young Charles-Nicolas Cochin.

On the threshold of a rotunda temple, a cherub comes flying in a cloud, holding at arm's length a banner reading "VIRGILE FRANÇOIS". In front of the open door stand the Muses. One of them invites the putto to enter.

Cochin by way of caption quotes below the engraving a line from Book VII of the Eneid: "Pandite nunc Helicona, Deæ " (Open to me now the Helicon, goddesses). To open the Helicon is, for the French Virgil, to pass the test of the epic, to be able to restore its original performative power. The text is represented in the image as a ritual of passage: one must pass the judgment of the Muses to be recognized as an essential poet (the Latin Virgil), a poet who belongs in their temple (the French Parnassus).

The putto is placed at the center of the visual cone that starts from the hidden interior of the temple; by making the temple a rotunda, Cochin installs a concentric system of representation and hypertrophies the threshold of the Holy of Holies that it is a question of penetrating. In this space, it's not an event that's represented, but a judgment: the event, Virgil's translation, comes from the outside on the left; the verdict of the judgment will come from the inside on the right. Between the event and the verdict, the judgment unfolds at the threshold of the temple the time, space and figures of its process27.

This judgment by the Muses is a judgment of taste: it designates the reception given to the book by the public, it makes the threshold of the temple the space where the public stands. The exercise of taste becomes the stake of representation, and taste is an experience of the threshold28.

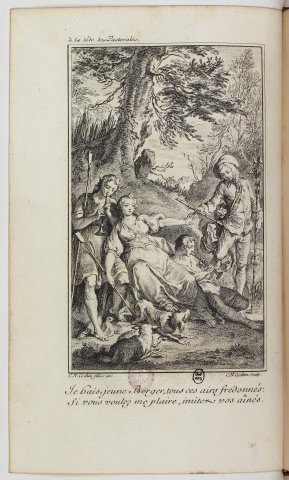

The age of criticism succeeds the age of eloquence and its theatricalization. The second engraving in the collection, which opens Les Bucoliques, represents this vividly. Instead of depicting one or more episodes from the text it precedes, it sets the scene for Des Fontaines' speech on the Pastorale, after which it is inserted.

At the center of the composition, a shepherdess sits between two shepherds playing a kind of straight flute with a wide bell. Like her, they are dressed very simply, without buttons, ribbons or hats. Two sheep and a dog complete the audience. Arriving from the background on the right, another shepherd appears, more richly dressed, holding a transverse flute in his right hand (a modern flute, that is) and a ribbon-laden staff in his left. With a graceful wiggle, he extends the hand holding the flute towards the shepherdess, as if to ask her permission to join the group. But she sternly pushes him away with her left hand, while her dog with its nail-studded collar raises its head and stiffens on its front legs, ready to pounce.

.The little peasant concert represents the Virgilian Pastorale, which Fontenelle's shepherd would come to corrupt. More political than Des Fontaines, Cochin makes Fontenelle's shepherd a naive, charming boy. While the peasant flautists remain absorbed in their playing, the shepherdess alone with her dog expresses her rejection, and her pout hardly wins over the reader, who will instead identify with the pretty, ribboned shepherd in Fontenelle's eclogues. It is Fontenelle's reader who comes face to face here with the rusticity of Virgil's text: the challenge is to enter it, to conquer the shepherdess.

The space where the shepherdess stands is delimited on the left by her staff, on the right by Fontenelle's shepherd's flute, these two lines converging towards the composition's vanishing point. The shepherdess stands in the visual cone that organizes the penetration of the viewer's gaze into the depths of this image: there's no need to insist here on the erotic game that Cochin, with his flutes and houlettes, indulges in, the whole perversity of which consists precisely in offering up for the eye a shepherdess who is in no way desirable.

To enter the cone, Fontenelle's shepherd will have to go around the first flautist, pass over his legs and come to stand before the young girl. His wiggle prefigures this circumvention. In other words, the spectator's eye, identified with the adolescent, will make a quarter-turn before positioning itself in the visual cone that orders the composition: the scenic device, which finds its ultimate expression here, thus recovers the quarter-turn of the altarpiece regime, but reverses its function: at the end of a procession, it is no longer a question of returning to the image and introducing a second vanishing line, but quite the opposite, at the beginning of the process, of delaying the installation of the single perspective and keeping the viewer in the time and space of the crossing.

By depicting not an episode from Les Bucoliques, but the critical debate affecting the poetics of the genre, Cochin manifests a much more general and profound transformation in the relationship of image to text: the debate is about what to read (Fontenelle or Virgil) and, within what is read, what to prefer. By staging this debate, the image is positioned here clearly after the text, as the place where judgment on its effects is exercised.

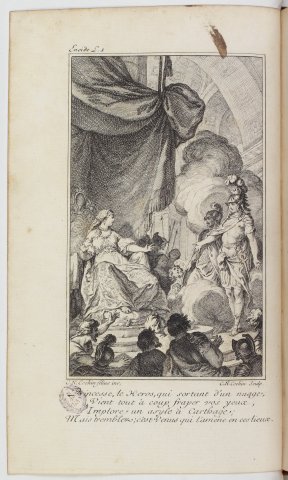

With the Énéide, Cochin doesn't allow himself such liberties: an iconographic tradition has been established, which pre-contracts the choice of sequences to illustrate. For Book I, Cochin depicts the episode of Dido granting hospitality to Aeneas in accordance with this tradition. But the political gesture of the queen granting protection to foreigners becomes a scene of encounter and first sight, captured in the double visual cone of crossed eyes. The regime of territories articulated the temple to the sea and the city; the regime of judgment focuses on the effect that the encounter produces on the spectators who witness it: the political dimension of the representation is no longer carried by the queen's gesture, but by the approval of the spectators; it no longer has to do with what marked the beginning of the event, but with the way in which it reverberates in the public space.

In the foreground, occupying the full width of the image, Cochin has depicted five spectators from behind: on the parterre this would be the front row in front of the ramp. In the left background, Dido is enthroned on a circular platform. Facing her, emerging from the cloud of Venus that had hitherto kept him invisible, Aeneas presents himself to the queen and smiles at her. It's a theatrical coup that leaves the audience speechless: that's the effect Cochin is aiming for. And indeed, neither Dido nor Aeneas does anything: arms open and dangling, they watch each other see each other, in a suspended moment of stupefaction that makes them smile, like actors sure of the effect they are about to produce.

Once again, everything is played out at the edge of the stage: Didon occupies the heart of it, Aeneas is about to invest it. Although placed on the first step of the throne, the standing young man, with his empanelled helmet, dominates the seated queen with all his head: he has already subjugated the queen.

It's all about the edge of the stage.

But, sensational as the show is, everyone remains in their place: the sharing of parterre and stage and the Italian perspective, thought out for an eye placed in the center of the parterre, are now common conventions and naturalized, as it were.

Conclusion

The comparative analysis of some of the classic illustrated editions of Virgil has enabled us to identify five successive regimes of representation. The performative regime is also the feudal regime; it is already obsolete at the beginning of printing, but survives in trace form until the generalization of scenic devices in the second half of the seventeenth century : linked to the Roman recitatio, which it supplanted, and to a syntagmatic conception of the image, it was rivalled from the period of the International Gothic by the régime narratif, which refers to solitary, scholarly meditative reading, as well as to an image-retable, designed for gazes to scroll before it. The narrative regime is at the same time a commercial regime: between the territories of representation, it organizes circulation and exchanges; in the image, it installs one, interfaces; the world-city, the port is the privileged place from which radiates this new organization, which is maintained in engraving until the early 17th century.

Progressively, the object of representation then evolves, from performance as action to eloquence as spectacular exercise: a discursive regime is put in place, highlighting in the image the word of the protagonist, who, from the stage of discourse, designates in the vagueness that surrounds him the events that are its subject. This is the age of eloquence, through which the industrious bourgeois can claim to participate in public administration: the discursive regime is also the regime of the royal administration that is being organized. A society of orders, with more rigid hierarchies, is taking shape: it assigns a place to the spectator and stages at its heart the eye that regulates its movements. The perspectival regime, characterized by the generalization of Italian perspective29, endorses the new political order born of the Fronde. The model of the tabernacle replaced that of the altarpiece: the image was read less laterally than in depth, and the organization of space was simplified and clarified in a bipartition between vague and restricted space, comparable to that of the parterre and the stage in theater. With the perspectival regime, the scenic device is put in place, regulated by a screen organizing the separation between the representation of events (soon to be simply vague space) and the representation of their representation (the stage proper, or restricted space). Attention thus gradually shifts from the representation to its effect, from the event to its repercussion in the public space: a critical regime gradually takes shape, encapsulating the restricted space between two visual cones, i.e. two sovereignties, of the reader and the vanishing point, of the audience and the sovereign.

.Notes

Probably commissioned by a Roman patrician of the late fifth or early fifth century AD, probably before the sack of Rome by Alaric in 410, the Vergilius Vaticanus originally contained the complete works of Virgil, a fragment of the Georgics and two fragments of the Aeneid reproducing much of the first nine cantos have survived; 50 miniatures have been preserved, and for the Eneid 32 images in a state of preservation sufficient for good analysis. The manuscript is kept in the Vatican Apostolic Library, under the shelfmark Vat. Lat. 3225. See David H. Wright, Vergilius Vaticanus, Graz, Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt (ADEVA), 1980, 2 vols. (facsimile and commentary) and The Vatican Vergil, a Masterpiece of Late Antique Art, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1993.

It seems that early illuminations on volumen were unframed. Evidence of this practice can be found in a 10th-century manuscript of Terence, Vat. Lat. 3868, which probably copies a much earlier manuscript.

On the recitatio, I take up the developments of Emmanuelle Valette-Cagnac, La Lecture à Rome, Paris, Belin, 1997, and in particular chap. III, which is essentially based on the testimony of Pliny the Younger. On the performance of the recitatio as co-creation of the text, see pp. 136-138. On the always disappointing experience of the recitatio, see Juvenal, Satires, VII, 38-53, and E. Valette's analysis (ibid., p. 114).

Publii Virgilii Maronis Opera, Strasbourg, J. Grüninger, 1502, in-folio, and Sébastien Brant, Das Narrenschiff, Basel, Johann Bergmann von Olpe, 1494 (Brant is the author of the text, whose illustration he entrusted to the young Dürer).

This image configuration is not systematic in the volume, but other examples can be found, such as on f. 4v°, on the engraving illustrating the IIe bucolique (#018611). The various moments illustrated in Corydon's song to Alexis are linked by Thestylis planted in the center, a bassinet on her head and a jar of water in her hand. A completely peripheral character in the text, Thestylis appears in the playlet of v. 10-11, where she brings the harvesters their meal. Thestylis the messenger, the provider, forms the symbolic pivot of the image, beneath Alexis and Corydon: for Corydon to sing Alexis, Thestylis must keep the household running...

On the double vanishing-point perspective system that developed from these altarpieces, see Franco and Stefano Borsi, Paolo Uccello, trans. A. Gubellini and M. Luxembourg, Paris, Hazan, 1992, pp. 154-155; on Lorenzo Monaco's model, see ibid. pp. 71-73. This work extends Erwin Panofsky's seminal La Perspective comme forme symbolique [1932], trans. G. Ballangé, Paris, Minuit, 1975, which itself drew on Guido Hauck, Die Subjektive Perspektive und die horizontalen Curvaturen des dorischen Styls: eine perspektivisch-ästhetische Studie, Stuttgart, K. Wittwer, 1879; Lehrbuch der malerischen Perspektive mit Einschluß der Schattenkonstruktionen: Zum Gebrauche bei Vorlesungen und zum Selbststudium, Berlin and Heidelberg, Springer, 1910.

Aeneid, I, 450-493; f. 141-142 (#008146). The same device is found with the painted walls of Apollo's temple at Cumae, f. 253 (#018475).

There are two scenes per register in the central arch. See detailed description on Utpictura18.

Likewise the depiction of the open interior of the temple where Dido and Anna make their sacrifices, f. 211r° (#018494).

I follow, for the order of the episodes, the argument below the engraving: "Quand le preux Turnus eut perdu ja sa vie | En combatant, ses gens font tout homaige [= allégeance] | Au pere Enee...", then "Alors Enee de sa chere maistresse | Fait les nopces", and "En fin bastit en la terre dotale [= received in dowry], la ville de Lavin".

Compare with representations of the Engagement or the Marriage of the Virgin. In Italy, the implementation of the altarpiece device and its scenic transformation came much earlier: Duccio's fresco in Padua, painted around 1303-1305, organizes a parade (#016666); Lippo Vanni's composition in Monteriggioni, 1360-1365, is installed between two doors through which guests can enter on the left and exit on the right (#015684), but we can already observe the implementation of a cavalier perspective with a single vanishing point; on Lorenzo Monaco's fresco at the Holy Trinity in Florence, 1420-1424, people line up behind the priest to come and congratulate the bride and groom (#018598) : Monaco exacerbates the parade regime; Ghirlandaio's 1485 fresco in Florence's Santa Maria Novella church (#013317) is set in a cavalier perspective with a single vanishing point, but retains the triptych structure; for Perugino, in the Caen painting (1501-1504), the temple remains tripartite, even if its relegation to the background accentuates the effect of the single vanishing point (#016663) ; Raphael, with a similar composition in 1504, abandons the tripartite structure of the temple (#016659); Dürer, between 1502 and 1510, introduces the depth of an apse behind the protagonists (#001784); Rosso Fiorentino in 1523 introduces staircases, and thus the stage effect (#016667); Jacques Stella in 1640-1645 reverses a device that is now sufficiently established to be played with: ascending steps behind instead of descending in front, dog turned away in the foreground (#016665). Royal weddings were composed after the standard scene of the Marriage of the Virgin: see, for example, Les Épousailles de la Reine in Rubens' Cycle de Marie de Médicis, 1621-1625 (#016639), or Le Mariage de Constantin, 1622 (#013203).

See Florence Dupont, L'Invention de la littérature, de l'ivresse grecque au livre latin, Paris, La Découverte, 1994, p. 199.

Translator Pierre Perrin, in the address to the reader that follows the dedicatory epistle to Cardinal Barberin opening the second volume, discreetly alludes: "This is the version of the second Part, or of the last six Books of the Eneïde, which I had finished long ago, but which troubles either public or domestic have prevented me until now from giving to daylight. "

The engraving is unsigned, but those for Book I and Book III are.

Iris acts at the behest of Juno, who is not depicted in the sky. But behind the funeral pyre, the port of Carthage is distributed in symmetrical architecture: on the left, under Aeneas' fleet, a simple tower; on the right, under Iris, the tower is surmounted by a statue of a goddess holding a scepter. This is Juno, protector of the city, before whose temple Dido granted Aeneas hospitality. So Bosse did depict Juno, but discreetly, without resorting to the marvellous. Juno, now a statue of Juno, blends into the landscape.

Abraham Bosse was very interested in questions of perspective. See A. Bosse, Manière universelle de M. Desargues, pour pratiquer la perspective par petit-pied, comme le géométral, ensemble les places et proportions des fortes et foibles touches, teintes ou couleurs, Paris, P. Deshayes, 1648, and Moyen universel de pratiquer la perspective sur les tableaux ou surfaces irrégulières, Paris, A. Bosse, 1653.

The tabernacle in question here is the tabernacle revisited by the Counter-Reformation after the Council of Trent. It reactivates a very old device, which had enabled the medieval Church to reconcile the cult of images with the biblical ban on representation. On this subject, see Stéphane Lojkine, "Entre économie et mimésis, l'allégorie du tabernacle" (online at Utpictura18), partially published in "De l'allégorie à la scène : la Vierge-tabernacle", in B. Pérez-Jean and P. Eichel-Lojkine (dir.), L'Allégorie de l'Antiquité à la Renaissance, Paris, H. Champion, 2004, p. 509-531.

The articulation of this political regime with the semiotic regime being established at the same time is schematized by Jacques Rancière in Le Partage du sensible, Paris, La Fabrique, 2000. Rancière jumps straight from Aristotle to Boileau, however, and doesn't take into account a Roman, then medieval and reborn regime of the image, which leads him to give his "poetic regime" far more scope than it can actually be considered to have had, from the end of the 17th to the middle of the 18th century, and to delay the advent of the "aesthetic regime", which, in the definition he gives, we can see taking hold throughout the Europe of the Enlightenment well before the French Revolution.

Pierre Perrin, in the address to the reader that follows the dedicatory epistle to Cardinal Barberin opening the second volume, discreetly alludes to it: "Voici la version de la seconde Partie, ou des six derniers Livres de l'Eneïde, que j'avois acheois depuis long-temps, mais que les troubles ou publics ou domestiques m'ont empesché jusqu'icy de donner au jour. "

Compare with the dog's gaze, in Books II and XIII of the Compendium of 1612.

On Chauveau's engraving for "La Cigale et la Fourmi" (A0898, 1668), the tree and its root squarely isolate the unlikely fable scene in the foreground - the dialogue between the two insects, from the visually more expected genre scene in the background - the woodcutters warming themselves by the fire. Several engravings from the English Virgil of 1654 also obey this principle: Aeneas and Achateus surveying preparations for Troy's departure (B7911), Aeneas plucking a dogwood branch dripping with Polydore's blood (B7912), Polyphemus seeing the Trojans flee to their ships (B7913).

Abraham Bosse had illustrated Tristan L'Hermite's Mariane in 1637 (#007983): the engraving depicted the confrontation between Mariane and the cupbearer, a false witness to her betrayal, before her husband Herod assisted by his council. Herod's madness, unable to decide between his love for the queen and the treason of which she is accused, represents the paralysis of the late feudal regime. Bosse does depict the king on a throne and under a canopy, with a single vanishing point cavalier perspective inviting the eye to enter the depth of the image; but this construction is parasitized by the representation of the council assisting the king, at the same height as him, and requires a lateral reading of the image.

Compare, for example, with the engraving of Act III of Quinault's Roland set to music by Lully, 2e (actually 3e) ed., Ballard, 1717 (#005537). On the harbor where Angélique and Médor's ship is already ready to embark for the Catay, Médor is raised to a throne and crowned king by Angélique's retinue. He holds his right hand over his heart and raises a scepter with his left arm. Another example: the engraving in Act II of Atys (same authors), ed. Ballard 1709 (#005548). Cybèle makes Atys her sacrificer; he is crowned by winged putti. Atys holds his right hand to his heart and brandishes the sacrificial knife with his left arm.

See, for example, Medea's arrival in Act IV of Quinault's Thésée set to music by Lully, in Scotin's engraving after Gillot for the 1711 edition (#005532).

This is the great fundamental division, which replaces the old system of territories (just as the classical Italian theater replaces the Baroque compartmentalized theater, which comes under the regime of the altarpiece). The absolute separation of parterre and stage did not become fully effective in France, however, until 1759 with the Lauragais reform.

In the classical age, backstage was not a room behind the stage, but a set of scenery panels sliding on rails at regular intervals on the stage. The most elaborate stage in this respect is that of the Opéra, which has six coulisses. See the article Coulisse in the Encyclopédie, by Cahusac.

The image is therefore read from left to right. However, it does not obey the regime of an altarpiece in front of which one scrolls: only one space properly speaking is represented, which is a threshold, i.e. itself a non-territory.

S. Lojkine, "Le goût de Diderot, une expérience du seuil", Recherches sur Diderot et sur l'Encyclopédie, n° 50, 2015, p. 45-59.

Italian perspective became widespread in illustrative engraving much later than in painting.

Référence de l'article

Stéphane Lojkine, « Régimes de la représentation dans la gravure d’illustration classique. Les Virgiles illustrés », Littératures classiques, vol. 107, n°1, 2022, p. 31-45. La version publiée sur Utpictura18 est une version corrigée après publication dans Littératures classiques.

Fiction, illustration, peinture

Archive mise à jour depuis 2006

Fiction, illustration, peinture

La scène de roman

La scène de roman : introduction

Renaud dans le jardin d’Armide

Rastignac chez Mme de Restaud

Gilberte derrière les aubépines

La poignée de porte de tante Berthe

La double aporie du topos

Illustrer la fiction

Molière, une parole débordée

Marillier, l’appel du mièvre

On n'y voit rien

Illustrations de l'utopie au XVIIIe siècle

Le temps des images

Du conte au roman graphique

Déconstruire l’illustration

Régimes de la représentation dans la gravure d’illustration classique

Penser la fiction depuis la peinture

Une sémiologie du décalage : Loth à la scène

Introduction à la scène comme dispositif : Paolo et Francesca

La main tendue, le regard démasqué

De Silène molesté à la chair blanche des nymphes

Chambres de la représentation

L'intimité de Gertrude

Brutalités invisibles

Parodie et pastiche de Poe et de Conan Doyle dans Le Mystère de la chambre jaune de Gaston Leroux

Le dispositif de la chambre double dans Les Démons de Dostoïevski

Scène pour voir et chambre des brutalités

La Princesse de Clèves

L’invention de la scène dans le roman français

La canne des Indes

L'aveu

La princesse, la religieuse et l'idiot

Richardson

Entre scandale et leurre

Introduction aux Lettres angloises, ou histoire de miss Clarisse Harlove, par Samuel Richardson